Life Lessons with Uramichi Oniisan is a Japanese comedy manga series by Gaku Kaze, primarily meant for the demographic of adult women or josei, as the Japanese word goes, and has been running since 2017. The primary genre it deals with is comedy, satirising both children’s entertainment as well as the growing mental health crisis in adults who live in the small island country of Japan. It was adapted into a short anime series by Studio Blanc, which was released in 2021.

The series focuses on the protagonist Uramichi Omota, a 31-year-old man who works as one of the hosts in a children’s show called Together with Maman, similar to the vein of real-life kids shows like Blue’s Clues and Sesame Street. Of course, like any other work of fiction with an ensemble cast, multiple other characters are also centred as the series progresses.

Since I have only watched the anime, I will be centring my discussions around it.

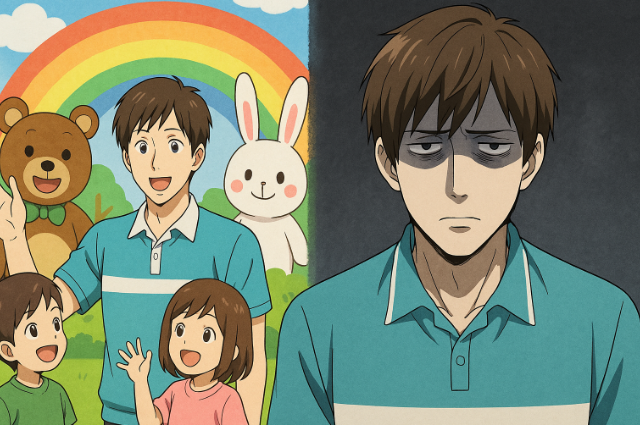

Behind the anime’s bright colours and childish opening, which brings a wave of nostalgia to the viewer, there is a cynicism within the characters and the show itself that makes for the perfect piece of entertainment. The characters’ positive role-model like figures they play for television is juxtapositioned against their pessimistic and sometimes downright suicidal mentality (though this is definitely a trait seen more in Uramichi) which can bring a sudden whiplash to the naïve viewer who might have sat down to watch the show with their child only to see the main character break down the rose-tinted view of the world that a child possesses.

Uramichi himself is seen to be a person who has given up on life, having long forgotten his dream of being a professional gymnast after an ankle injury, as he fakes his smiles in front of the camera for an overbearing director and the kids who participate in the programme. A sentiment that is very much true for the audience, especially the jaded adults who have not lived up to their dreams or have abandoned them in favour of society’s expectations. Hopelessness has seared into the flesh of almost every person in the show. From Utano’s constant attempts to get married to have a “normal” life, and Mitsuo’s apathetic attitude towards everything in life, is painfully relatable. Striving for normality has become a priority, and in the process, happiness is thrown away.

There is no happy ending to this story. However, the manga addresses a bigger question.

Is it normal to be hopeless?

It seems to be a theme that seems ongoing, hidden behind the comic aspects and one-off jokes, just like the number of cigarettes that Uramichi smokes during his break. The trapping of oneself within a cynical bubble – joking about suicide and helplessness seems ideal for an adult in a world that is cruel and self-serving. After all, humour breaks all semblance of weakness as we pass the hurt onto a fictional person.

In the end, Uramichi Oniisan and the others are just fictional.

Right?

The show constantly contrasts the colourful worldview of the children with the jaded worldview of the adults working in the show. Aside from the comedic sarcasm that occasionally escapes the mouths of the children, they are generally optimistic, happy, and look upon the cast members as role models. To these children, they resemble real-life examples of children’s show entertainers like Mr. Rogers, Steve from Blue’s Clues and Ms. Rachel, complete with the bright colours, skits and life lessons that they are supposed to carry to their grave. Perhaps, more darkly, Uramichi Onii-san indicates that the only way to be an adult is to be depressed.

Hopelessness also takes on different forms when it comes to gender. Uramichi’s lack of hope stems from his professional failure, having to suffice as a mid-range children’s entertainer (who is often sexualised for the audience of mothers, too) instead of becoming a famous gymnast who could make him and his country proud. Side character Utano also faced misfortunes in her career, but her priority is marriage, constantly comparing herself to younger women who have gotten married while she is still stuck in a rut with her comedian boyfriend. Societal norms, particularly in Asian countries, fixate upon marriage for women and career for men as the ultimate goals. Despite being close in age, their priorities differ due to society’s judgment. Unmarried women in their thirties are seen as old hags who are past their prime, while unsuccessful men are perhaps considered emasculated due to their role. Thus, societal expectations can also play their part in the growing crisis of mental health among people.

Ironically, the one character who seems to be content with life is the one who acts the most like a child. Iketaru Daga, portrayed by voice actor Mamoru Miyano, in the original Japanese version, is one of the secondary entertainers of the show who complete the singing duo by providing the male voice. Unlike the other characters who are characterised by their depression, Iketaru is surprisingly calm and content. In the series, he is turned into a laughing stock, but one could argue that having a childlike outlook on life could help navigate this bleak world a lot better than being swept away by its malevolent current. Since he is easily amused by childish jokes and is rather optimistic in his view, he is perhaps the happiest character (as seen based only on the anime).

Therefore, the anime highlights the bleakness that comes with adult life, which is masked under pretty lights, colours and the façade of normalcy.

Sources:

Life Lessons with Uramichi Oniisan (うらみちお兄さん)