One winter evening, sitting with a childhood friend over chai, I asked him why he still engaged in political fights on social media even though they left him drained. He smiled, half embarrassed, and admitted, “Peace feels boring. I need the drama.” Have you ever thought about that? How even when things are calm, part of us itches for conflict — whether it’s a heated debate, a rivalry, or just a quarrel that adds spice to the monotony. It sounds counterintuitive because we claim to long for peace, but the evidence, both scientific and personal, suggests otherwise: humans are strangely, almost perversely, drawn to conflict.

The Evolutionary Roots of Restlessness

If we zoom out, evolution offers a blunt answer. Our ancestors lived in harsh, unpredictable environments. Survival meant constant vigilance — against predators, rival tribes, and hunger. Peace wasn’t the norm; it was an interlude between storms. Anthropologist Lawrence Keeley estimated in War Before Civilization (1996) that pre-state societies had violent death rates of 15–25%, compared to less than 1% in modern states. In other words, conflict was once the default, not the exception.

Actually, psychologists argue that our nervous systems are still tuned to that environment. The fight-or-flight response floods the body with adrenaline and cortisol at the slightest provocation. Peace, ironically, can feel unnatural — like a silence so loud it makes us uneasy. Neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux’s work shows how quickly the amygdala reacts to threats, far faster than the rational brain. We evolved to prioritize conflict signals because missing one could mean death.

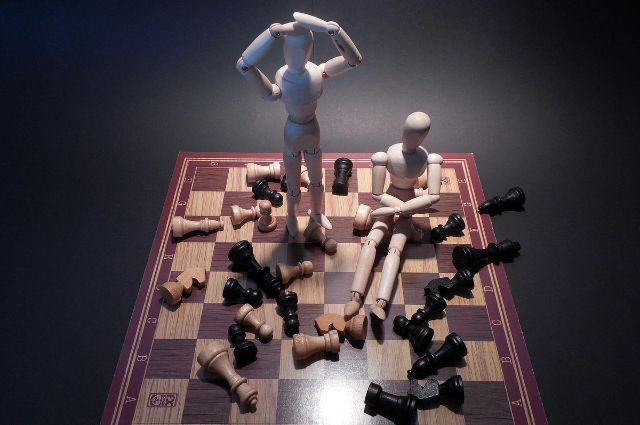

Peace as Boredom, Conflict as Stimulation

But it’s not just biology. On a psychological level, peace often registers as boredom. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s research on “flow” found that humans crave optimal challenge — situations that are difficult enough to engage us but not impossible. Peace, in its purest sense, removes challenge, leaving a vacuum.

Could you look at crime statistics? In countries where violent crime has sharply declined — such as the U.S., where the violent crime rate has dropped by 49% since 1993 (FBI data) — people paradoxically perceive society as more dangerous. A 2016 Gallup poll revealed that 57% of Americans believed crime was rising, despite decades of decline. Psychologists call this the “mean world syndrome” — when peace prevails, our minds invent threats to stay stimulated.

I see this in my own family. After my father retired, the household grew quieter. For months, he complained of “too much peace.” He started picking small arguments with neighbours — about parking, noise, cricket loyalties. It wasn’t malice; it was restlessness. Conflict, even petty, gave him something to push against.

The Politics of Perpetual Conflict

You know what’s fascinating? Leaders and governments understand this craving and exploit it. Carl von Clausewitz once said, “War is the continuation of politics by other means.” Modern politics often flips it: peace is maintained through low-grade conflict.

A study by Harvard’s Steven Pinker argued that we live in the most peaceful era in history, with wars and battle deaths steadily declining since World War II. Yet, why does it feel otherwise? Part of it is media amplification. A Pew Research Center study in 2019 found that two-thirds of Americans said news media focus too much on conflict rather than solutions. Conflict sells because we are wired to consume it.

I remember scrolling Twitter during the India-China border skirmish in 2020. Even people who usually avoided politics became glued to updates, hungry for drama. The fear of peace — of a calm feed — was palpable. Conflict, even distant, gave us something to rally around, argue about, and obsess over.

Sports: War by Other Means

If peace feels unnatural, perhaps that’s why sport exists. Anthropologists often describe sport as “ritualized conflict.” It channels aggression into symbolic battlefields. The numbers back this up: the 2018 FIFA World Cup final drew 1.12 billion viewers worldwide. Why such a massive audience? Because a ball kicked across grass became a proxy for tribal war.

In India, nothing illustrates this better than India vs Pakistan cricket. A study by Nielsen in 2019 estimated that more than 273 million people watched their 2019 World Cup clash. That’s almost the population of the U.S. combined with half of Europe. If you think about it, why do we care so much about eleven men hitting a ball? Because it scratches the ancient itch for conflict in a way that peace never could.

I still remember watching that match with my father. Every moment felt like life and death. When India won, the joy wasn’t just about cricket — it was the catharsis of having lived through three hours of managed conflict.

The Personal Magnetism of Struggle

On an individual level, conflict shapes identity. Psychologists at Stanford University (2010) found that people who overcame obstacles reported higher levels of meaning in life than those who described their lives as easy. Struggle, it seems, is essential to purpose.

I’ve seen this with friends. One of them thrived during exam pressure, another during political protests in college. Both confessed that calm periods made them feel “empty.” It wasn’t that peace was unpleasant, but it lacked texture. Conflict gave their days a sense of urgency, like a story worth telling.

Actually, I’ve noticed this in myself too. During quiet weeks when classes, writing, and life run smoothly, I sometimes pick arguments online — not because I care deeply, but because the friction jolts me awake. Peace can feel flat; conflict sharpens the edges.

The Business of Manufactured Conflict

Marketers exploit this relentlessly. Advertising often thrives on creating conflict: between old and new, tradition and innovation, you and your “lesser” self. A 2020 Nielsen report showed that brands using competitive or combative narratives saw 23% higher engagement than those promoting harmony. Even reality TV is built on conflict. Bigg Boss in India consistently ranks among the highest TRPs because it packages quarrels as entertainment.

Social media supercharges this. Facebook’s own internal 2018 report admitted that posts triggering anger got five times more engagement than neutral ones. Algorithms know we can’t resist conflict; they feed it to us.

The Dark Side of Peace

Of course, conflict isn’t always healthy. Prolonged conflict breeds trauma, anxiety, war, and division. Yet here’s the paradox: when societies achieve peace, individuals often generate micro-conflicts to fill the void. Marital counsellors note that couples frequently fight more after retirement, not because love fades but because the absence of external struggle turns partners into sparring partners.

One therapist friend told me, “Couples come to me saying they want peace, but when they get it, they can’t stand the stillness. So they fight over who left the towel on the bed.” It’s almost comical — peace itself becomes the enemy.

Toward a Truer Peace

So, do humans secretly crave conflict? The data, stories, and our own restless hearts suggest yes. But maybe the real challenge isn’t to erase conflict, but to channel it. Psychologists recommend “productive conflict” — debates, sports, creative struggles — as outlets that satisfy our craving without leading to violence.

Think of Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance. It was still in conflict, but transmuted. Or think of the way art, literature, and protest harness friction to spark growth. Perhaps peace doesn’t mean the absence of conflict, but the presence of meaningful conflict.

Conclusion: The Restless Heart

You ever notice how the quietest nights feel the loudest inside your head? That’s the thing about peace — it doesn’t always soothe us; sometimes it unsettles us. Neuroscience might explain it with brain chemistry, sociologists might blame society’s hunger for spectacle, but if I’m honest, it’s more personal than that. Peace can feel like staring into a mirror too long. It forces you to face yourself, without distraction, and that’s terrifying.

So maybe we don’t really crave war or fights — maybe we just fear the emptiness peace leaves behind. That silence makes us restless, so we pick little battles: with neighbours, with strangers online, even with the people we love. We say we want calm, but the moment life gets too calm, we itch for friction.

In the end, peace isn’t some magical opposite of conflict. It’s just the stage where conflict decides whether to enter or stay backstage. And maybe the real trick isn’t to run toward the storm or hide from it, but to choose which storms are worth walking into — and which silences we can actually learn to live with.

References

- Keeley, L. H. (1996). War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage. Oxford University Press.

- LeDoux, J. (1998). The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Simon & Schuster.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). (2021). Uniform Crime Reports: Crime in the United States, 1993–2020. Washington, D.C.

- Gallup. (2016). Perceptions of Crime Continue to Conflict with Reality. Gallup News.

- Pinker, S. (2011). The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Viking.

- Pew Research Center. (2019). Americans’ Attitudes About the News Media Deeply Divided Along Partisan Lines. Pew Research Center.

- FIFA. (2019). 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ Global Broadcast and Audience Summary. Fédération Internationale de Football Association.

- Nielsen Sports. (2019). Cricket World Cup 2019: Global Viewing Figures. Nielsen.

- Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301.

- Nielsen. (2020). The Role of Conflict in Advertising Engagement. Nielsen Insights.

- Facebook Internal Research. (2018). An Analysis of Engagement Metrics: Anger and Virality. (Reported by The Wall Street Journal, 2021).

- Gottman, J. (1994). Why Marriages Succeed or Fail. Simon & Schuster.