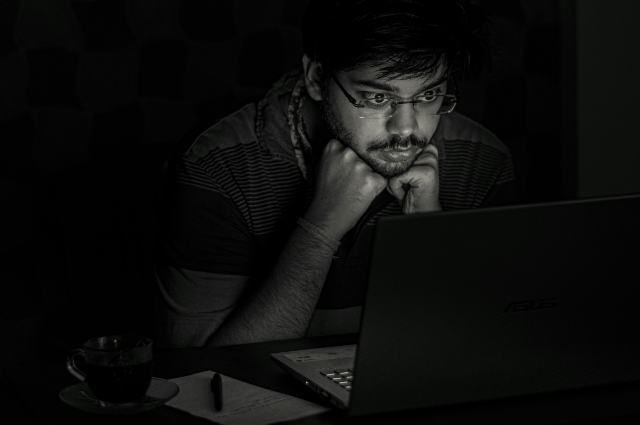

Photo by Pranjall Kumar on Unsplash

There has been a quiet but deepening shift among India's youth in recent years. From urban professionals who pop into co-working offices to students at India's best universities, the formerly celebrated hustle culture is increasingly met with exhaustion, cynicism, and outright ridicule. What was once hailed as drive is now increasingly met with suspicion, as more and more young adults begin questioning the cost of constant productivity. Burnout, anxiety, and chronic exhaustion have become the new normal, and for an increasingly large segment of Indians in their twenties and early thirties, the appetite for constant work and achievement is giving way to an appetite for rest, meaning, and a more sane pace of life. This shift, though quiet and often individual, is evidence of a deeper disillusionment with the neoliberal idea that constant "grinding" is required in order to be approved of.

The rise of hustle culture in India was not a standalone phenomenon. It was driven by the rapid processes of economic liberalization, urbanization, and the spread of startup culture, propagated by social media platforms that celebrated long working hours, side hustles, and self-actualization. For a considerable chunk of middle-class Indians, especially in urban India, the concept of hustle became synonymous with success. The "rise and grind" culture was adopted as a badge of honor, wherein sleep deprivation and resultant engagement in jobs were accepted as indicators of aspiration. The trend was most pronounced in technology industries, management schools, and creative industries, where the line between personal aspirations and professional competence tended to get blurred. But beneath the superficiality of unlimited productivity was a spreading sense of hollowness. Many were left wondering if there was always a better quality of life with more effort.

The pandemic was a principal driver of this disintegration. As the world came to a standstill in 2020, a significant number of young Indians—suffocated in small living spaces or having withdrawn to family dwellings—were compelled to pause and question their relationship with work. The abrupt disintegration of routine, the dissolution of professional and personal life, and the psychological cost of solitude made the flaws of hustle culture all the more apparent. A 2021 survey conducted by LinkedIn found that 74% of Indian professionals felt burnt out over the last year, with Generation Z and millennials being the worst-hit groups (LinkedIn Workforce Confidence Index, 2021). The overwork culture was not merely unrealistic—it was toxic.

As a consequence of this shared fatigue, a more restrained type of resistance has resulted. Much of young India is increasingly seeking alternative patterns of work and living that emphasize balance over speed, depth over breadth, and well-being over mere performance. This can be seen in the growing popularity of minimalism, slow living, and even the "anti-work" culture that has erupted on online platforms such as Reddit and Instagram. What one increasingly finds common are statuses about sabbaticals, career simplification, avoiding corporate ladders, or simply getting by on "just enough" rather than over-performing. For others, this is a political act. The avoidance of toxic productivity also arises from rejecting the capitalist culture that builds human worth upon economic productivity. As writer Jenny Odell expounds in her book How to Do Nothing, distance from the attention economy is not an exercise in laziness but a form of resistance. While her ideas were conceived within a Western context, they have started resonating with Indian readers battling similar challenges.

The critique of hustle culture is driven by the increasingly visible Indian youth mental health crisis. It is estimated that 10% of Indian adults have common mental disorders, with much higher prevalence among the 18–29-year-old age group, according to the National Mental Health Survey of India (2015–16). Urban youth, in specific, are at the receiving end, caught by high expectations, precarious job markets, and societal pressures to perform round-the-clock. While therapy and mental health awareness have become the norm in Indian cities, they remain out of reach for many and rarely touch the underlying sources of burnout, including overwork, poor labor rights, and economic inequality. In this way, the choice to adopt slowness transcends individual survival mechanisms; it is a survival act.

One of the key drivers of this shift is the growth of the gig economy and freelance work, which, as promising as it was in its early days for its flexibility, has delivered new forms of precarity. The initial freedom of freelancing is replaced by the harsh reality of unpredictable incomes, blurring of work and personal life, and a constant burden of being "on call." Young Indian freelancers today talk of the phenomenon of the "freedom trap," where flexibility is purchased at the expense of insufficient rest. The romanticization of freelancing, remote work, and entrepreneurial culture is being put under critical scrutiny by those who have suffered its built-in uncertainty. Online forums and podcasts written by young Indian professionals and creatives like The Swaddle, All Indians Matter, or Agla Station Adulthood are increasingly discussing these issues, giving voice to a generation's fatigue with the constant on-call-ness that this lifestyle necessitates. This shift away from hustle culture is more a redefinition of ambition than a rejection of it. For some, success is no longer measured by promotions, pay increases, or fame. Rather, there is a new hunger for work that is values-aligned, leaves room for rest, and generates room for life beyond the professional. Some are going back to their hometowns, others are quitting high-stress corporate jobs for community activism or artistic endeavors, and many are simply deciding to do less with less shame. This shift is messy and not without contradictions; many still work within systems that reward overwork but the cultural mindset has permanently shifted.

In fact, this movement is not an option for everyone. The privilege of class predominantly determines who can choose to opt out of certain environments. While some segments of urban upper-middle-class youth have the economic capital to exit bad jobs or take sabbaticals, for many working-class Indians, the hustle is not an option but a survival mechanism. In a nation with high youth unemployment and weak social safety nets, a refusal to engage in productivity is an unmistakable badge of privilege. This sentence does not imply that the critique of hustle culture is unfounded; it is rather a plea for contextualization within larger debates about labor rights, access, and systemic inequality.

Authentic resistance against poisonous productivity models must involve not only individual refusal but also demands for structural reform—better labor laws, universal basic income, mental health resources, and a cultural re-evaluation of our metrics of success. The silent rebellion against hustle culture among India's youth continues to unfold. This rebellion is typically driven by no particular banner, no manifesto cause. But its power lies in the ordinariness of it sleeping in over an extra shift, refusing paid internships, and choosing people over LinkedIn. This movement is a harsh reminder that life is not a game to be won but a life to live. When the world is too busy trying to gain more, the act of doing less consciously, mindfully, and unapologetically may just be the most revolutionary act of all.