Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, published in 2003, is arguably one of the most polarising and widely discussed novels of the 21st century. As a fast-paced thriller blending art history, symbology, cryptography, and religious conspiracy theories, it captured the imagination of millions and spurred endless debates among readers, critics, historians, and theologians. Despite mixed critical reception, its commercial success was unprecedented — selling over 80 million copies worldwide and spawning a successful film adaptation, sequels, parodies, and even scholarly critiques.

This review delves into the novel’s plot, character development, thematic elements, writing style, cultural impact, and the controversies it stirred, offering a nuanced view of why The Da Vinci Code remains a landmark in popular fiction.

Plot Overview

The novel begins with the murder of Jacques Saunière, curator of the Louvre, inside the museum’s Grand Gallery. His death sets off a chain of cryptic clues that Saunier leaves behind, implicating Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon, who is in Paris for a lecture. Langdon is soon joined by Sophie Neveu, a police cryptologist and Saunier’s estranged granddaughter.

What follows is a whirlwind chase across France and the UK as Langdon and Sophie unravel a series of puzzles involving Da Vinci’s artwork, secret societies like the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei, and hidden messages allegedly embedded in religious texts and Renaissance art. Their journey centres on the search for the Holy Grail — not the traditional chalice of legend, but a symbolic treasure hidden for centuries that could shake the foundations of Christianity.

At the heart of the novel is the assertion that Jesus Christ was married to Mary Magdalene and fathered a child, whose bloodline continues to the present day. According to Brown's fictional narrative, this secret was suppressed by the Catholic Church and protected by the Priory of Sion for centuries.

Characters and Development

The characters in The Da Vinci Code are functional rather than deeply nuanced, serving as vehicles for the plot rather than fully fleshed-out personalities. However, they are distinct and serve important thematic and narrative roles:

- Robert Langdon: A Harvard professor of symbology, Langdon is the calm, analytical centre of the story. He represents rationalism and academic curiosity. Langdon's expertise allows him to decipher the symbolic riddles Saunier leaves behind, but his character often acts more as a conduit for exposition than as a deeply introspective individual.

- Sophie Neveu: A cryptologist with a tragic family past, Sophie adds emotional depth to the narrative. Her connection to Saunier and the revelation of her identity serve as crucial elements of the story. She is intelligent and resourceful, but often plays second fiddle to Langdon in terms of driving the investigation.

- Leigh Teabing: A wealthy British Grail scholar and ex-historian, Teabing is eccentric and passionate about revealing the “truth” behind Christianity. His role as an antagonist is one of the more surprising twists, though some may find his transformation melodramatic.

- Silas: An albino monk and self-flagellating assassin working for Opus Dei, Silas is a tragic, brainwashed figure driven by religious fervour. While he is cast as a villain, Brown gives him enough backstory to render him sympathetic, though stereotypical portrayals of mental illness and albinism have drawn criticism.

- Bishop Aringarosa: The high-ranking Opus Dei official who believes he is serving a higher cause, Aringarosa reflects the novel’s theme of blind faith versus moral ambiguity. Like Silas, he is ultimately a pawn in a larger game.

Brown’s characters often suffer from a lack of complexity, and their emotional development is minimal. However, their archetypal qualities allow the plot to move quickly and serve the story’s puzzle-like structure.

Themes and Symbolism

- Religion and Faith

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of The Da Vinci Code is its interpretation of Christian history. Brown presents a narrative where the Church is portrayed as an oppressive institution that manipulated sacred truths to consolidate power. The claim that Jesus was married and that Mary Magdalene was sidelined by patriarchal forces questions centuries of Christian doctrine.

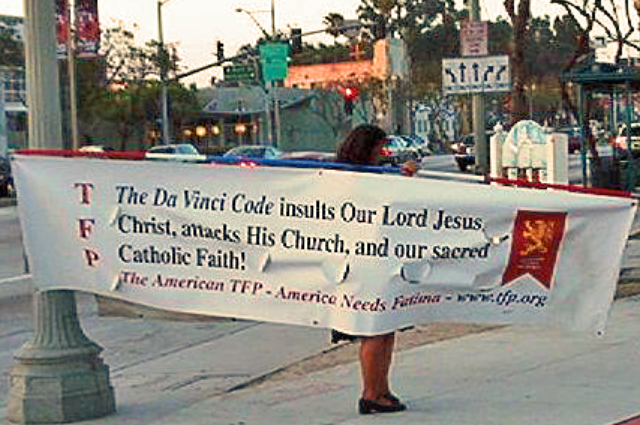

While many readers understand this as fictional speculation, others — especially religious scholars — criticised it for blurring fact and fiction. Brown’s use of real organisations like Opus Dei, presented as shadowy and sinister, further intensified the controversy.

However, the novel is not entirely anti-religious. It explores the nature of faith, asking whether belief must be rooted in literal truth or whether spiritual value transcends historical accuracy. Sophie's journey, from scepticism to a more personal understanding of faith, reflects this tension.

- Feminism and the Sacred Feminine

A significant theme is the suppression of the “sacred feminine” within religious tradition. Mary Magdalene is reimagined not as a repentant prostitute, as per traditional interpretations, but as a holy figure equal to Jesus — a vessel of divine femininity whose legacy was deliberately erased.

This theme resonated with many readers, particularly those interested in feminist theology and alternative spiritualities. However, critics argued that the novel oversimplifies or distorts history to make its point.

- Symbols and Secrets

Brown structures the entire novel as a puzzle. Clues hidden in Da Vinci’s paintings, anagrams, codes, and ancient texts form a narrative that requires constant decoding. The idea that ancient knowledge is hidden in plain sight — in art, architecture, and history — gives the novel its allure.

The symbols themselves — such as the Fibonacci sequence, the Vitruvian Man, and the pentacle — are real, though their meanings are often fictionalised. Brown’s blending of fact and fiction is one of the novel’s most effective and contentious techniques.

Writing Style and Structure

Dan Brown’s prose has been widely criticised as pedestrian or formulaic. The writing is utilitarian, with short chapters and cliffhangers designed to propel the reader forward. While this makes for a compulsive page-turner, it also sacrifices depth and stylistic sophistication.

Dialogues often serve as exposition, with characters explaining history or symbology in long paragraphs that feel more like lectures than organic conversation. Critics have also pointed out Brown’s overuse of certain phrases and his sometimes-awkward sentence constructions.

However, the structure — alternating between perspectives, inserting twists, and gradually revealing a layered conspiracy — is undeniably effective. Brown’s mastery of pacing and suspense keeps readers engaged, even if the prose itself is not particularly elegant.

Historical Accuracy and Controversy

The most heated debates around The Da Vinci Code stem from its presentation of pseudo-historical claims as factually grounded. Brown famously begins the novel with a “Fact” page, stating that certain elements — including the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei — are real. While technically true, this is misleading:

- The Priory of Sion: A real organisation, but it was established in 1956 as part of a hoax by Pierre Plantard, not an ancient secret society as the novel claims.

- Opus Dei: A legitimate Catholic organisation, but its depiction in the book as a shadowy, violent cult is an exaggeration that has drawn criticism from Church officials and media analysts alike.

- Mary Magdalene and the Holy Grail: The idea that Mary Magdalene was married to Jesus and that her bloodline exists is based on interpretations of Gnostic texts and fringe theories. These are presented as credible alternatives to orthodox Christian teachings in the novel, leading to widespread confusion among some readers.

Despite these issues, Brown insists that The Da Vinci Code is a work of fiction. However, the blending of fact and fiction is so seamless in places that many have taken its theories at face value — something scholars have worked to debunk through books, documentaries, and academic articles.

Reception and Impact

Critics were largely unimpressed with The Da Vinci Code on a literary level. Many panned the writing, character development, and historical liberties. However, readers voted with their wallets: the novel became a global phenomenon. It topped bestseller lists, was translated into over 40 languages, and inspired a blockbuster movie starring Tom Hanks as Robert Langdon.

More importantly, it rekindled public interest in art, history, and alternative religious narratives. Museums reported spikes in visitors eager to see Da Vinci’s works. Religious scholars found themselves drawn into public debates about the nature of historical truth. The book even inspired travel tours to Paris, London, and Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland, where key scenes unfold.

In the literary world, The Da Vinci Code spawned a subgenre of religious-conspiracy thrillers, and Brown himself continued the Robert Langdon series with Angels & Demons, The Lost Symbol, Inferno, and Origin — each exploring similar themes with varying success.

Conclusion: A Flawed but Fascinating Thriller

The Da Vinci Code is not a perfect novel — not even a particularly well-written one by literary standards. Its characters are shallow, its prose is clunky, and its manipulation of history borders on irresponsible. Yet it succeeds where many novels fail: it captivates, provokes, and entertains.

The book’s real strength lies in its ability to turn obscure historical and religious topics into compelling mysteries. For all its faults, it sparked meaningful conversations about faith, history, and the role of women in religion. Whether you admire or criticise it, The Da Vinci Code is a novel that leaves an impression — and that is perhaps the ultimate mark of impactful storytelling.