Photo by Garv Chaplot on Unsplash

Sounds That Cleanse and Fragrances That Heal

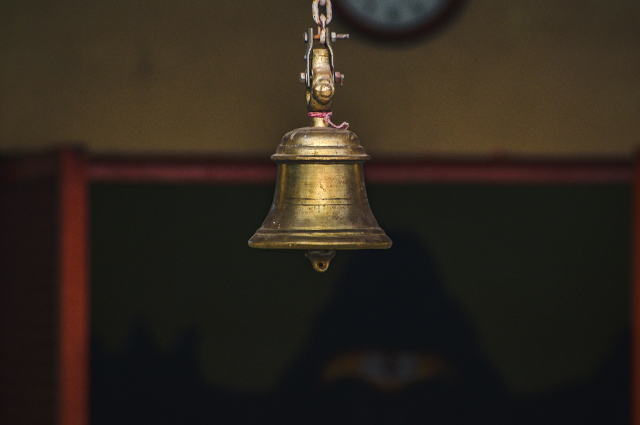

Anyone who has ever stepped into an Indian temple knows the atmosphere is different. The air feels thicker, heavy with incense smoke, and in the middle of chanting or silence, suddenly a loud bell rings. The sound fills the chamber, sharp and deep, echoing off the walls, and for a moment, your own thoughts break. Along with it, the smell of burning incense stays in the background, weaving itself into memory. These things have become so ordinary in temple visits that we rarely stop to ask why. Were they just symbolic acts invented by priests, or is there something deeper, maybe even scientific, hidden in these simple rituals?

Take the temple bell first. It is not just an iron object struck for noise. Most bells are made from a mix of metals like copper, zinc, bronze, and

sometimes even silver or gold in trace amounts. The shape of the bell is not random either. It is carefully designed so that when struck, it produces a sound frequency that lasts longer than a few seconds and spreads in waves. People who have studied acoustics say the vibration is strong enough to touch the nerves in the ear and calm the brain. That one strike can shift the wandering mind into focus, a bit like how a sudden clap in a classroom brings restless students back to attention.

But bells are not only about psychology. Some scientists argue that the sound waves can disturb harmful bacteria in the surrounding air. Even if this is debated, what cannot be ignored is how sound itself changes mood and energy. A temple is supposed to be a place where you leave behind distractions, and the bell almost forces that moment of clarity. It is like a reset button before prayer begins. That is why old texts even say you must strike the bell before entering, so that “evil thoughts” do not follow you inside. Today, we might replace that phrase with “restless thoughts,” but the effect is not very different.

Now think of incense. Burning sticks or powders made from resins, herbs, wood, or oils have been used not just in India but across the world. Modern laboratories have found that some of these ingredients release antibacterial agents, which clean the air. Frankincense, sandalwood, neem, and camphor — each has compounds that can reduce insects, germs, or at least neutralize bad odor. In an age before sprays and air purifiers, incense was a simple way to keep a gathering space cleaner. But beyond hygiene, smell works directly on the human brain. The nose is connected to memory and emotion more deeply than other senses. A certain fragrance can calm anxiety,

another can make you alert, and another can even bring back buried memories. Priests might not have spoken in terms of neurons and chemicals, but they saw the effect clearly. Smoke calmed crowds, it created rhythm in rituals, and it kept people returning because the atmosphere felt holy.

Old Traditions Meeting Modern Curiosity

It is interesting how many rituals that feel purely religious often overlap with science once you examine them slowly. Bells, incense, and even the layout of a temple often line up with patterns of energy, sound, and human psychology. For example, the garbhagriha, the innermost chamber where the deity is placed, is usually small, stone-walled, and dark. The sound of the bell is amplified much more strongly, creating an almost vibrating chamber that touches the body itself. The incense in that closed room spreads quickly, so every breath taken in is filled with those calming compounds. When you kneel or sit inside, you are not just praying—you are sitting in a controlled environment that changes your senses, a mix of sound therapy and aroma therapy without ever calling it that.

Some argue this is all a coincidence. That may be priests just wanted to impress worshippers with drama and mystery. But if you look at how carefully these rituals were passed down and repeated, generation after generation, it feels more deliberate. Ancient people might not have had microscopes or speakers, but they were observers. They saw which sounds cleared the mind, which herbs reduced illness, and which smells made people feel peaceful. Over time, these practices entered ritual, and ritual became tradition. Science got covered with layers of faith, but it never disappeared completely.

Think also of timing. Bells are not rung once but again and again during aartis. Incense is not lit for one moment but kept burning slowly. The repetition makes sure the effect lasts. Modern studies in meditation show how repeating chants or breathing patterns over time has stronger effects on brainwaves. In the same way, a temple ensures that the senses are surrounded, not for a second but for the whole duration of worship. This continuity is what makes the experience memorable.

Of course, there are skeptics who say we should not force science into everything old. And they are right to a degree. Not every ritual has a scientific explanation. Some were symbolic, some were social, some were simply habit. But the point is not to strip rituals of faith. It is worth noting how faith and observation once walked together. When an old grandmother tells a child to strike the bell properly or not to waste incense, she might not use the language of “vibration frequencies” or “antibacterial compounds,” but the wisdom behind it is not so different.

Rituals as Human Inventions, Not Just Divine Commands

Looking at temple bells and incense this way opens a bigger question: are rituals divine commands or human inventions? Maybe they are both. Humans built the temples, shaped the bells, mixed the incense powders. But they did it in a way that connected to something larger. By attaching them to gods, they made sure the practices were respected and carried on. After all, if you told people thousands of years ago, “strike this metal so your brain relaxes” or “burn this herb to kill germs,” maybe the advice would fade away. But if you told them, “Do this for the gods,” then suddenly the act gained power and endurance. Faith preserved science in its own way.

Even today, when many of us are more skeptical, the rituals still survive. A bell still rings in temples and sometimes even in homes. Incense is still lit in small rooms, sometimes more for the smell than for devotion. We may not always believe in the same gods or chant the same hymns, but the body still responds. The sound still cuts through noise, the fragrance still calms the nerves. That shows that rituals, beyond faith, tap into something universal.

Maybe that is the hidden science: rituals work not because people blindly obey, but because they touch human senses in ways that matter. They gave rhythm to life, they gave comfort, and they tied people together in shared acts. Even now, walking into a temple and hearing the bell, smelling the smoke, we know instantly that we have stepped into a space that is different from the street outside. And that difference is what makes us pause, breathe, and for a few moments, feel part of something larger than ourselves.