“Sometimes when you give up food, you feed the soul instead.”

The Spiritual Side of Fasting

Fasting has always held a special place in Indian traditions. For many people, it is not just skipping a meal; it is seen as a test of will, a prayer in itself, and a way of showing devotion that goes beyond words or rituals. From Karva Chauth, where women go without food and water the whole day for the well-being and long life of their husbands, to Ekadashi, which comes twice every month and is tied to the phases of the moon, fasting is treated like a sacred promise. In both cases, it is not only about self-denial, but also about intention. When someone chooses to fast, they are in a way saying that for this day, I will control my body so that my spirit can take the front seat.

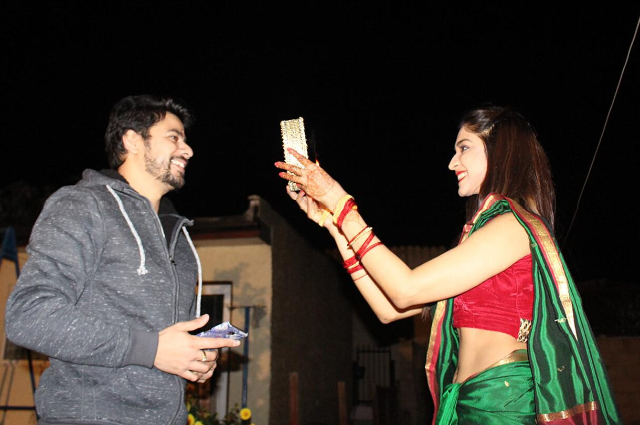

If you look closely, every fast carries a story. Karva Chauth, for example, has become known for its dramatic image of a woman holding a sieve and looking at the moon before she drinks water, but the heart of it is deeper. It is about faith, about waiting patiently, about aligning yourself with the rhythm of the moon and the cycle of life itself. Similarly, Ekadashi is tied to Lord Vishnu and is considered the most powerful day for cleansing the soul. The scriptures say that by fasting on Ekadashi, one can break free of sins and also control desires. Here again, the body is only the tool; the goal is to discipline the restless mind.

There are many other fasts too — Navratri, when people give up grains or certain foods for nine days, Maha Shivratri, when some do not even drink water until the night, Pradosh Vrat for Lord Shiva, and Chhath Puja, where fasting is mixed with rituals around the sun. Each one has different rules, but the thread running through them is the same: fasting is seen as a sacrifice that leads to strength, patience, and purity. It is like telling the self, “If I can let go of food, I can let go of many other cravings that disturb me.” And in that sense, fasting has been a training ground for centuries, a kind of spiritual gym where the exercise is not lifting weights but lifting yourself above hunger.

For elders in villages, fasting is often remembered not as punishment but as peace. They will tell you that on days of fasting, the body feels lighter, prayers feel more focused, and the mind becomes calmer. You hear fewer demands from the senses, and so you can hear more of the inner voice. In modern life, where everyone eats, snacks, scrolls, and consumes without pause, fasting reminds us that restraint can be beautiful. It teaches you that you are not a slave to your stomach; you are more than that.

Health and Hidden Science

What is interesting is that modern science has slowly started to say things that traditions knew long ago. Doctors now talk about intermittent fasting, about how giving your body a break from constant eating helps in repairing cells, balancing hormones, and even slowing aging. Researchers show that when you stop eating for 12–16 hours, the body shifts into a mode where it burns stored fat and begins a kind of clean-up process called autophagy. This is not very different from what our ancestors practiced, only they framed it in the language of faith.

Karva Chauth, Ekadashi, and Navratri fasts — each one, in its own way, gives the stomach rest. Our ancestors probably noticed that this break from heavy food made people feel better, lighter, sometimes even more energetic. They may not have used medical words, but they understood the rhythm of body and nature. If you eat all the time, the body is always busy digesting. If you pause, you can focus on healing. And by tying this pause to the cycle of the moon or the calendar of gods, people made sure they would not forget to practice it regularly.

There is also a psychological angle. When you tell yourself, “I will not eat until the moon rises” or “I will not touch grains on this day,” you are training the brain in discipline. Hunger is one of the strongest impulses we have, and controlling it even for a few hours gives you confidence that you can control other impulses too. It is like proving to yourself that you are stronger than your cravings. And this discipline often spills into other areas of life. People who fast regularly sometimes speak of better focus, less attachment to material things, and a sense of achievement that goes beyond food.

On the health side, fasting is also linked to detox. While the word detox has become fashionable today, in practice, it just means giving your system rest. When you eat light or skip meals, the body processes what is already inside instead of piling up more. For some, this shows as better digestion, for others clearer skin, and for others a drop in stress. Of course, not every fast food suits every person, and medical conditions must be considered. But the general idea that the body benefits from rest is hard to deny.

Another layer is community. Fasting is rarely done in isolation. During Karva Chauth, women gather together, share stories, wait for the moon, and break their fast as a group. During Ekadashi or Navratri, families sit together for prayers, cook special light meals in the evening, and spend time in devotion. This shared discipline builds bonds. In many ways, fasting is less about you suffering alone and more about reminding yourself that you belong to a larger rhythm, whether it is family, community, or the cosmos.

And maybe that is why fasting never went away. In times when food scarcity was common, fasting had survival value. In times when abundance and overeating are common, fasting has health value. In times when life feels scattered, fasting has spiritual value. So whether you see it as devotion, as discipline, or as science, the gesture is still the same — pause, let go of food, and discover what else feeds you.

Fasting then becomes more than a ritual. It is a reminder that power does not only come from consuming but also from controlling love can be shown by sacrifice, that faith can be proved by patience, that health can be protected by restraint, from Karva Chauth to Ekadashi, from grand rituals to quiet personal vows, fasting has always carried this mix of meanings and maybe the reason it has lasted through centuries is because at its heart it speaks to something universal the human need to find strength not just in what we take in, but also in what we choose to give up.