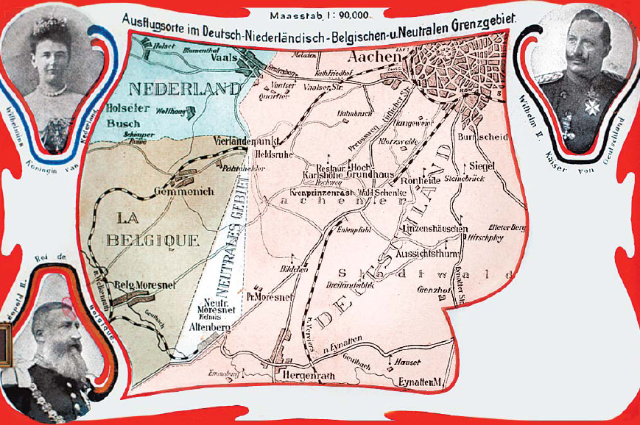

In the chaotic aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the great powers of Europe convened at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to redraw the continent's map, striving to create a brand new and lasting balance of power. Borders have been shifted, kingdoms have been created, and empires have been solidified. Yet, amidst this grand reordering, a tiny and nearly comical dispute among the brand new United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Prussia led to the accidental start of one of history’s strangest geopolitical oddities. The point of rivalry changed into a small, triangular plot of land of approximately three. Five square kilometers, centered on the precious Vieille Montagne zinc spar mine near the city of Kelmis. Unable to agree on which nation needs to owns this mineral wealth, the diplomats settled on a weird temporary compromise: the territory might belong to neither, but would instead be administered together as a neutral rental till a future settlement may be reached. This provisional solution, intended to be transient, might remain for 104 years, giving upward thrust to the extraordinary, quasi-impartial country of Neutral Moresnet.

Life inside this geopolitical loophole was in contrast to everywhere else in Europe. Governed by a mayor who was appointed by external commissioners—one from Prussia and one from the Netherlands (later Belgium after its independence in 1830)—the inhabitants of Moresnet existed in a state of quasi-anarchy. The territory had no status army, and its male citizens had been effectively exempt from the military conscription of its powerful associates. Taxes had been incredibly low, and its criminal reputation changed into ambiguous, making it a natural haven for those living on the margins. The population swelled with smugglers, political refugees, navy deserters, and marketers looking to capitalize on the particular situations. For a time, Neutral Moresnet boasted several distilleries generating gin and a casino, both of which were unlawful or heavily regulated in the surrounding countries. The citizens themselves, a mix of German, Dutch, Belgian, and other nationalities, were technically considered stateless, further cementing the territory's identification as a curious anomaly—a stateless state born not from revolution or self-determination, however, from the simple lack of ability of two empires to agree on a border.

As the nineteenth century drew to a near, the zinc mine—the territory's complete cause for being—started to be depleted, threatening Moresnet with obsolescence. Faced with the possibility of being absorbed by its associates, the community sought a new cause, which arrived in the form of a splendid utopian imaginative and prescient. Dr. Wilhelm Molly, the local physician and an ardent proponent of the newly created worldwide language of Esperanto, proposed a radical idea: to transform Neutral Moresnet into the arena's first actual Esperanto-speaking state, to be named Amikejo ("Place of Friendship"). The plan changed into creating a global beacon of internationalism and neutrality inside the heart of an increasingly more nationalistic Europe. This formidable inspiration captured the imagination of the global Esperanto movement, which saw it as the ideal possibility to set up a tangible place of birth for his or her linguistic perfection. Enthusiasm was high; a proposed countrywide anthem, the "Amikejo March," was composed, and plans had been made for an international congress to be held inside the territory to promote the purpose. For a brief, constructive moment, it appeared this tiny sliver of land ought to become a worldwide center for a non-violent, post-nationalist destiny.

The dream of Amikejo, but, becomes a utopian imaginative and prescient in an international unexpected descent into battle. The exhaustion of the zinc mine by 1885 had eliminated the territory's primary monetary value, and its persistent lifestyles were a source of growing infection to its powerful buddies, particularly the newly unified and assertive German Empire, which made numerous attempts to annex it. The sensitive stability that had allowed Neutral Moresnet to survive for a century was shattered by the outbreak of World War I. In August 1914, Germany invaded Belgium and occupied the territory, unilaterally ending its neutrality. After the conflict, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles definitively settled the century-old dispute, formally awarding the previous condominium to the Kingdom of Belgium. With the stroke of a pen, Neutral Moresnet was erased from the map, its 104-12 months history as a geopolitical twist of fate brought to an unceremonious close. Today, it exists simply as a historic footnote, a fascinating testimony to the extraordinary and regularly absurd consequences of political compromise and a forgotten degree for considered one of history’s maximum curious utopian experiments. Neutral Moresnet’s afterlife lingers in subtle traces: border stones swallowed by hedgerows, a museum in Kelmis, and placenames that once marked a quadripoint now reduced to a tourist waypoint on the Vaalserberg ridge, where three flags meet but a fourth is only memory. Its improbable civic experiments—tax haven improvisation, quasi-stateless leniency, and the Esperanto dream of Amikejo—anticipated modern debates about micro-sovereignties, special economic zones, and post-national identity long before the vocabulary existed. In a Europe repeatedly re-soldered by treaties, Moresnet’s century proved that law can freeze ambiguity into daily life, and that ambiguity can, in turn, generate culture, opportunity, and myth. When the pen finally ended in 1919, what disappeared was not only a border but a laboratory: a place where compromise hardened into a country, language was proposed as law, and neutrality became narrative. Its lesson is simple: accidents can found nations, and bureaucracy can birth utopias. Pls - The Accidental Country: The Bizarre 104-Year History of Neutral Moresnet

References=

- Neutral Moresnet — https://en.wikipedia.org

- Tiny Country Neutral Moresnet Became Part of Belgium — https://www.the-low-countries.com

- The History of Neutral Moresnet, Europe’s Forgotten Microstate — https://www.thecollector.com

- Formerly Neutral-Moresnet, now Kelmis — East Belgium Tourism — https://www.ostbelgien.eu