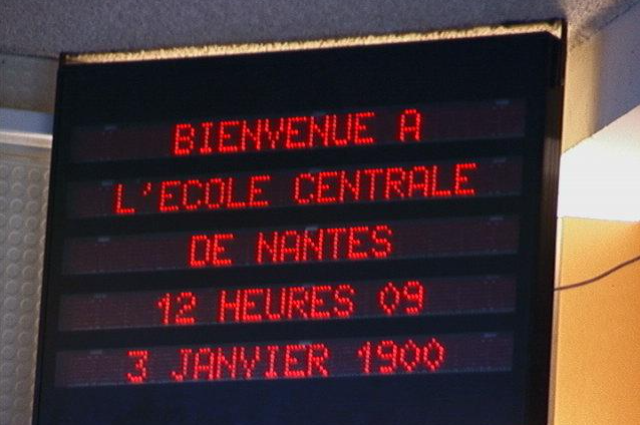

At the heart of the incredible Y2K panic lay a simple, pragmatic shortcut that has been a pillar of right programming for decades. In the pioneering era of computing within the Nineteen Sixties and 70s, information storage became a treasured and exorbitantly luxurious aid. A unmarried megabyte of memory ought to cost hundreds of dollars, forcing programmers to be ruthlessly efficient with each unmarried byte of data. To store space while handling dates, they adopted a nearly widespread convention: they represented the year using its final digits. For decades, "75" turned into an unambiguous shorthand for 1975. This smart trick, replicated in infinite traces of code across hundreds of thousands of structures, created a hidden time bomb. As the 20th century drew to a close, a chilling awareness dawned upon the arena's computer scientists: on January 1, 2000, those legacy systems could interpret the brand new date "00" now not as the 12 months 2000, however as the year 1900. This became no longer an insignificant beauty glitch; it became an essential flaw that threatened to motivate catastrophic failures in any time-sensitive calculation. The "Y2K Bug," also called the Millennium Bug, was expected to unleash virtual chaos upon the very infrastructure of modern civilization, from banking and air visitors manipulate to power grids and army systems.

By the late 1990s, the Y2K Trojan horse had converted from an obscure technical difficulty into a full-blown global panic, fueled by breathless media coverage and a burgeoning enterprise of specialists predicting a virtual apocalypse. News reviews broadcast dire warnings of a global world thrown into disarray: planes were anticipated to fall from the sky, nuclear missile systems were expected to malfunction, bank vaults might refuse to open, and whole economies could crumble as monetary structures, attempting to calculate interest over a span of one hundred years, crashed into oblivion. A lifestyle of millennial anxiety took hold, with survivalists stockpiling canned items and emergency mills, and most important organizations removing big insurance rules in opposition to the approaching technological meltdown. In reaction to this existential risk, the sector mobilized in what became arguably the most important and maximum costly engineering challenge in human history. Governments, militaries, and agencies poured an estimated $300 to $ hundred billion globally into remediation efforts. It became a frantic race against time, as armies of programmers had been pulled out of retirement to painstakingly comb through billions of strains of archaic, often undocumented code, looking for and patching every digit date they could locate.

On the night of December 31, 1999, the world held its collective breath. In high-tech command centers from the White House to the headquarters of every most important financial institution and airline, groups of experts sat nervously, looking at large screens as the brand new millennium rolled throughout the planet’s time zones. The first primary take a look at came as nighttime struck in New Zealand and Australia. The international community waited for information on the first breakdowns, the first signs and symptoms of the predicted chaos. But the reports that got here again have been… quiet. As the wave of dead nights swept throughout Asia, Europe, and eventually the Americas, a profound and surprising anti-climax spread out. The international infrastructure did not fall apart. The electricity grids stayed on, the economic markets prepared to open, and planes remained adequately in the air. While there have been a handful of teenybopper, remote glitches—a bus price ticket gadget in Australia printed the wrong date, a few slot machines in Delaware temporarily failed—the prophesied digital doomsday never materialized. The overwhelming feeling turned into one of significant remedy, which quickly gave way to a pervasive and cynical backlash: the entire Y2K panic, many concluded, had to had been a huge and costly hoax.

The narrative that the Y2K computer virus became an overblown fraud, however, fundamentally misunderstands the character of the occasion. The global community did not experience away catastrophic event because the hazard was imaginary; it escaped disaster because the big, globe-spanning, and astronomically costly remediation effort had been a wonderful success. The tale of Y2K is a conventional example of the prevention paradox: whilst a first-rate disaster is correctly avoided via cautious planning and hard work, the public is frequently left with the impression that the danger never became real in the first location, making the preventative measures appear to be a silly waste of time and money. The truth is that the bug changed into a very real one, and the outcomes of state of inactivity might have been excessive. The unseen legacy of the Y2K project became a forced, worldwide improve of the world’s critical digital infrastructure, leaving systems greater robust and secure than they had been before. It changed into additionally a rare and top notch instance of world cooperation on a shared, technical risk. The quiet sunrise of the new millennium changed into not proof of a hoax, but rather a silent monument to an invisible triumph—one of the most successful disasters that by no means occurred.

References-

- Year 2000 problem (Y2K) — https://en.wikipedia.org

- Y2K bug | Definition, hysteria, and facts — E Britannica — https://www.britannica.co

- Y2K Explained: The real impact and myths — Investopedia — https://www.investopedia.com

- Y2K | National Museum of American History (Smithsonian) — https://americanhistory.si.edu