In the grand narrative of biology, demise is the inevitable final chapter. For every complex animal, the life cycle is a one-way street: beginning, increase, reproduction, senescence, and finally, cessation. This procedure of getting old and rotting is considered a fundamental and inescapable regulation of nature. In the overdue Nineteen Eighties, however, a sequence of quiet, accidental observations in a laboratory petri dish might screen a creature that seemingly defies this regulation. A younger German marine-biology pupil named Christian Sommer changed into studying the life cycles of tiny, difficult-to-understand hydrozoans when he noticed something bizarre about one precise species, Turritopsis dohrnii. After accomplishing its grown-up, sexually mature stage, the tiny jellyfish, in place of death, appeared to be ageing in opposite. It would fall apart in on itself, its cells re-differentiating, till it had reverted absolutely to its earliest life degree, a juvenile polyp, from which it could begin its life all over again. It turned into a discovery so profound and so opposite to established organic dogma that it would take years for the medical community to completely grasp its implications: here was an animal that had, in a totally real sense, carried out biological immortality.

The mobile mechanism that offers Turritopsis dohrnii its top-notch ability is an extraordinary and effective biological process referred to as transdifferentiation. In most multicellular animals, inclusive of human beings, cell development is an extraordinarily specialised, terminal process. A stem cell differentiates into a nerve cell, a muscle cell, or a pores and skin cell, and this is its identity for the remainder of its existence. Transdifferentiation is the high-quality ability of a mature, specialised cell to convert directly into a very specific type of specialised cell. When the immortal jellyfish is faced with a mortal risk—which includes bodily damage, starvation, or the simple decay of antique age—it can initiate a lovely, whole-frame transformation. The person medusa (the loose-swimming jellyfish form) sinks to the seafloor, its bell and tentacles retract and are absorbed, and its entire frame regresses right into a cyst-like blob of tissue. Within this blob, the cells go through a large reprogramming, with muscle cells turning into nerve cells, or nerve cells becoming egg cells, until the entire organism has been rebuilt into the shape of a polyp, the desk-bound, juvenile shape of a jellyfish. From this polyp, new, genetically identical medusae subsequently bud off, each beginning the life cycle anew. It is the organic equivalent of a butterfly, upon reaching antique age, transforming back into a caterpillar to be reborn.

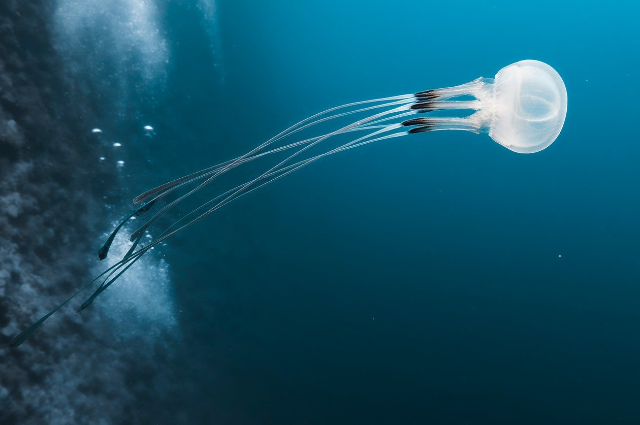

It is crucial to understand that this organic immortality no longer makes the jellyfish invulnerable. Turritopsis dohrnii isn't indestructible; it's merely ageless. In the wild, those tiny creatures—no larger than a human fingernail—are regularly fed on by predators or can succumb to sicknesses that kill them too fast for the transdifferentiation method to be initiated. Their immortality is an ability that isn't always constantly found out. It is a biological break-out hatch, a final survival method that allows the organism's genetic lineage to persist through intervals of severe environmental pressure. If a selected ocean surroundings becomes too cold, too warm, or without food, the jellyfish can really hit the reset button and anticipate conditions to enhance before beginning its life over. This first-rate potential has additionally made it a relatively successful invasive species. By hitching rides inside the ballast water of worldwide cargo ships, the immortal jellyfish has spread from its local Pacific to oceans throughout the globe, its unique life cycle permitting it to survive adverse journeys and colonise new territories with unparalleled performance.

The discovery of an animal that holds the secret to dishonest loss of life has, unsurprisingly, made Turritopsis dohrnii an item of extreme scientific fascination, in particular for researchers in regenerative medicine and the examine of getting older. While the possibility of human immortality remains in the realm of science fiction, the jellyfish gives a biological Rosetta Stone for cellular reprogramming and restoration. Scientists are now running to map the genome of Turritopsis to perceive the unique genes and proteins that orchestrate the transdifferentiation system. The last purpose isn't to reverse human ageing, however, to learn how to spark off comparable regenerative pathways in our very own cells. If we want to understand the genetic "switch" that permits a jellyfish's muscle cells to grow to be stem cells or nerve cells, it may free up revolutionary new remedies for repairing tissues damaged by means of injury or age-related diseases like Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, or heart failure. The humble immortal jellyfish, therefore, gives more than just an organic interest; it offers a profound supply of insight and a tangible blueprint for a future in which we might discover ways to command our very own mobile equipment with the same regenerative mastery, fundamentally converting the human experience of sickness and the process of growing old itself.

References