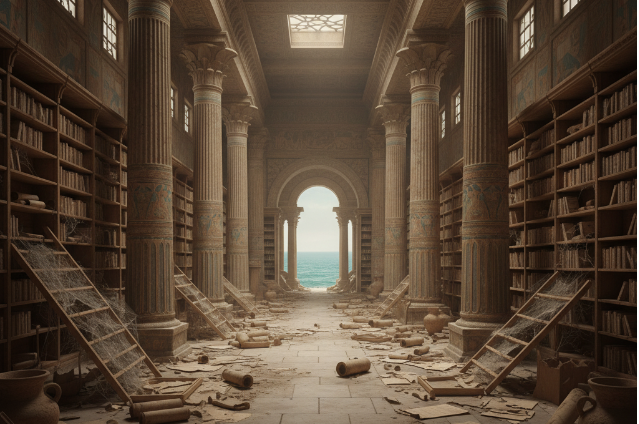

In the collective imagination of the Western world, the Great Library of Alexandria holds a place of profound and tragic reverence. It represents a misplaced golden age, a dream of ordinary knowledge snuffed out in a unmarried, catastrophic act. The story is a familiar one: a wonderful building at the seashores of the Mediterranean, housing the accrued awareness of the entire ancient international, tragically consumed through flames, plunging humanity right into a darkish age. This vision, however, belongs more to the realm of delusion than to history. The reality of the Library is each more complex and, in lots of ways, greater inspiring. Founded in the 3rd century BCE through the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt after Alexander the Great, the Library was the centerpiece of a pioneering studies institute referred to as the Musaeum, or "Shrine of the Muses." It became no longer simply a repository of scrolls, but the historical world’s first and best think tank, a country-funded hub of scholarship that attracted the most exceptional minds of the Hellenistic global. Its ambition became breathtaking: to gather a copy of every sizeable text on Earth. Agents had been dispatched across the recognized world to purchase scrolls, and a famous law decreed that any e-book found on a ship docking in Alexandria’s harbor would be seized, copied through a legion of scribes, and the replica returned to its proprietor, with the original being brought to the Library’s collection.

The famous narrative of the Library’s destruction is a historic whodunit that has been instructed for hundreds of years, with a rotating forged of villains. The most well-known suspect is Julius Caesar. In forty eight BCE, for the duration of his civil war, Caesar determined himself besieged in Alexandria and set fire to his personal ships inside the harbor to dam an enemy fleet. The heart unfolded to the docks and nearby warehouses. Some ancient writers, like Seneca, later wrote that forty 000 scrolls stored in those warehouses had been destroyed. This incident is the in all likelihood origin of the "notable fire" delusion, but no contemporary supply, including Caesar himself, claims that the Great Library itself was harmed. Later culprits have been nominated to fit the biases of the next era. In the 4th century CE, a Christian mob led by the Patriarch Theophilus destroyed the Serapeum, a temple in another part of Alexandria that housed a smaller, "daughter" library, an act which later became conflated with the destruction of the primary organization. Centuries after that, a story turned into a fabrication blaming the 7th-century Muslim conqueror, Caliph Omar, for burning the scrolls for fuel—a story now universally disregarded by historians as propaganda. The attraction of those single-occasion narratives is their simplicity; they provide a dramatic focal point for the loss of ancient understanding and a clean villain responsible for a perceived fall from grace.

The contemporary historical and archaeological consensus is that the Library of Alexandria was no longer destroyed in a unmarried, cataclysmic event. Instead, it suffered a sluggish and agonizing decline over the course of nearly seven centuries—a dying via 1000 cuts. Its fading turned into a symptom of the broader decay of the society that had created it. The first principal blow came no longer from a fireplace, however, from a political purge. In 145 BCE, the tyrannical king Ptolemy VIII, searching to consolidate his power, expelled all foreign scholars from Alexandria, inflicting a large "mind drain" that the Musaeum never absolutely recovered from. As the Ptolemaic dynasty weakened and Egypt was finally absorbed into the Roman Empire, the beneficial state investment that had been the Library's lifeblood began to dry up. The painstaking and pricey system of obtaining, translating, and, most importantly, re-copying the delicate papyrus scrolls faltered because of price range cuts and neglect. Parts of the gathering had been possibly misplaced to smaller fires, dispersed to different cities, sold off, or, in reality, crumbled into dust within the humid Mediterranean weather. The final blow turned into cultural, because the highbrow currents of the past due Roman Empire shifted away from the pagan, classical, and clinical inquiries that the Library had championed.

The actual tragedy of the Library of Alexandria, therefore, turned into no longer the loss of a single building, but the slow dissolution of the intellectual environment it represented. The actual fireplace became the sluggish burn of dwindling finances, political instability, and cultural apathy. While the lack of endless precise texts is a profound sorrow for historians, it is probable that the maximum essential knowledge contained within the Library's scrolls has been copied and disseminated to different outstanding collections in Rome, Pergamum, and Constantinople long earlier than the organization’s very last, unrecorded demise. The enduring legacy of the Library isn't the myth of its destruction, but the modern electricity of its founding concept. The dream of creating a commonplace repository of human know-how, a place wherein students from all backgrounds may want to collaborate to push the boundaries of knowledge, has become a foundational best for Western civilization. That spirit no longer died inside the smoke of a legendary fireplace; it turned into reborn inside the monasteries that preserved texts through the Middle Ages, within the universities of the Renaissance, in the outstanding national libraries of the Enlightenment, and, ultimately, in the boundless, interconnected archive of the net. The construction is long gone, but the Library's dream of a world illuminated by using shared know-how is more alive nowadays than ever before.

References -

- Library of Alexandria — Encyclopaedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com

- Library of Alexandria — Wikipedia (overview, sources, debates on destruction): https://en.wikipedia.org