The records and culture of humanity aren't just a series of dates and names; they are a nonstop, dynamic story of the way humans connect, innovate, and express their values. To find a truly significant subject is to discover a moment or movement that acts as a pivot point—one that fundamentally changes the trajectory of civilization.

Two such subjects stand out for their profound impact, bridging technological advancement with radical cultural transformation: the Gutenberg Printing Revolution and the contemporary era of Cultural Globalization and Hybridity. These movements show that whether through ink on paper or data across the internet, the sharing of ideas is the most powerful engine of human history.

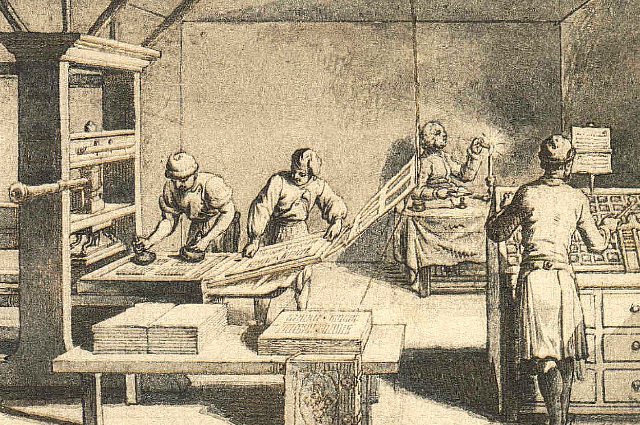

The invention of the movable-type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 CE was arguably the single most crucial moment in the cultural history of the Western world. Before this, books were luxury items, meticulously hand-copied in scriptoriums by priests, making literacy and knowledge privileges reserved for the ecclesiastical elite and wealthy nobility. The European mindset was largely communal and hierarchical, with authority flowing down from the Church and the King, and the scarcity of information maintaining a stable yet intellectually stagnant society.

The printing press shattered this paradigm. Suddenly, texts could be reproduced quickly and relatively cheaply. This shift from information scarcity to abundance triggered a cascade of cultural and historical effects. One immediate impact was the standardization of language; mass-printed books favored local tongues over Latin, strengthening the development of national languages such as English, French, and German.

More significantly, the press empowered the individual. When people began reading the same texts—the Bible, classical philosophy, scientific treatises—they did so privately. This act of solitary reading encouraged personal judgment and critical thinking, laying the cultural foundation for the Enlightenment.

Historically, the printing press was the essential tool behind both the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. Renaissance scholars used it to circulate rediscovered Greek and Roman texts, accelerating the movement that celebrated human reason and creativity. Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses spread rapidly due to print, transforming a local dispute into a continent-wide religious and political revolution.

Without the printing press, the Scientific Revolution—dependent on rapid exchange of experimental data and theories among scholars like Copernicus and Galileo—would have been impossible. Thus, the Printing Revolution was not merely a mechanical innovation; it was a cultural event that shaped the modern, informed, and individualized human mind.

The second cultural movement shifts from the fifteenth-century mechanical revolution to the twenty-first-century digital one: the impact of modern globalization on cultural identity. Today, with the internet, affordable travel, and global media networks, cultures interact, merge, and evolve at unprecedented speed.

For decades, the chief fear was cultural homogenization: that Western consumer culture and media would flatten the world into a single identity, erasing local traditions. While this influence is visible, the deeper reality is more complex. Globalization has fueled cultural hybridization. Rather than simply consuming foreign content, people remix and reinterpret it.

This is evident in music, food, and fashion. The global rise of K-pop, for example, is a hybrid blending African-American musical traditions with Korean cultural aesthetics and global media strategies.

However, this rapid cultural exchange also brings challenges. Discussions of cultural appropriation versus cultural exchange have become central, raising questions of representation, ownership, and authenticity. Meanwhile, digital media connects the world while also fragmenting it into polarized "digital tribes."

Analyzing cultural globalization means recognizing this tension: the same force that unites the world also divides it into tightly protected identities.

. . .

Reference