India's freedom struggle and social reform movements did not remain isolated to political leaders or city elites. Behind the grand narratives of independence was the struggle of millions of Adivasis, Dalits, and marginalized groups who struggled for justice, dignity, and equality. Their struggle was not just against colonialism or feudal domination, but also against the ingrained social and economic inequalities that deprived them of access to land, education, and fundamental human rights.

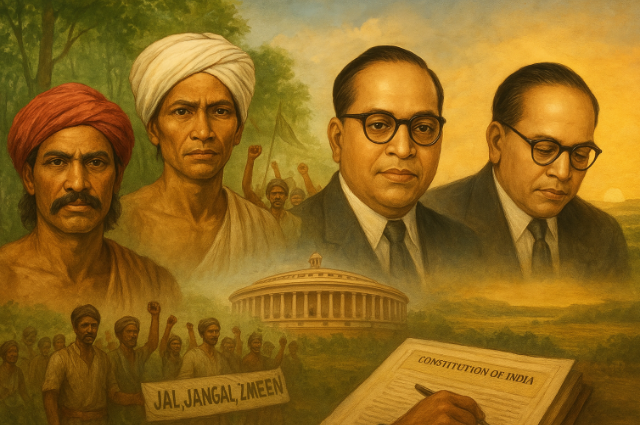

Among all these voices of protest are four giant figures — Komaram Bheem, Birsa Munda, Jaipal Singh Munda, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar — who rose from various parts and walks of life but with one vision in common: to empower the downtrodden and to build an India founded on equality, justice, and self-respect. Each of them represented a unique dimension of the struggle — Bheem and Birsa through armed resistance and community mobilization, Jaipal through political representation and advocacy, and Ambedkar through constitutional reform and intellectual leadership.

Their activism was based on the real lives of their people — the Adivasis who had been stripped of their "Jal, Jangal, Zameen" (Water, Forest, Land) and the Dalits who suffered from untouchability and exclusion. The combination of these leaders converted localized resistance into an overall movement towards social change.

This piece aims to discover the common heritage and interconnected ideals of these four visionaries. It explores how their battles, even as differentiated by time and space, came together in purpose — building a fair and dignified India where each individual could live with honor, unexploited. Their lives give us a reminder that the history of India's march is incomplete without noting the voices arising from its periphery.

Komaram Bheem: The Voice of the Forests

Komaram Bheem (1901–1940) was one of the most fearless leaders of tribal rebellion in Deccan. Born in Sankepalli village of what is now Komaram Bheem–Asifabad district of Telangana, Komaram was a member of the Gond tribe, one of the large Adivasi groups dwelling within the dense forests of central India. The Gonds spent their existence closely intertwined with nature — relying on forests, water, and land for subsistence. But under the regime of Hyderabad's Nizam, these people were subjected to ruthless exploitation in the form of heavy taxation, forced labor, and land alienation. Forest rights were withheld from them, and local landlords (zamindars) subjected tribal families to harassment and confiscated their agricultural harvest.

Seeing these injustices, Komaram Bheem emerged as a leader among his people. Having never had a formal education, he drew upon his strong knowledge of the forest and the ethos of solidarity that existed among the Adivasis. His slogan of "Jal, Jangal, Zameen" (Water, Forest, Land) became the battle cry for tribal autonomy — an agitation that represented not merely economic rights but also cultural and political independence. Bheem's vision was that Adivasis needed to own and control the resources that fed them for generations.

Bheem mobilized the tribal population of many villages, pitting them against the officials of the Nizam and the local landlords. His movement was founded on self-reliance, bravery, and joint resistance. He formed alliances between contiguous tribes and persuaded them to refuse to pay unfair taxes. The Nizam government, under threat from his increasing popularity, initiated military operations to put down the movement. Komaram Bheem was martyred in an encounter at Jodeghat in 1940, which put an end to his life but marked the beginning of an enduring legacy.

Even in his death, Bheem's ideals motivated generations of Adivasis not only in Telangana but also elsewhere. As a testament to his work, the government of Telangana in 2016 rechristened the Asifabad district as Komaram Bheem–Asifabad. A memorial cum museum at Jodeghat is now a reminder of his sacrifice.

Komaram Bheem's battle was not merely a tribal uprising but a battle for human rights and environmental justice. His vision of self-governance on the principles of equality and ownership of resources is pertinent to the issues of tribal displacement, nature conservation, and indigenousness that confront India today. Bheem is still an icon of defiance — a voice that continues to resound in the jungles, reminding India of its incomplete mission of justice for its earliest occupants.

Birsa Munda: The Tribal Messiah

Among India's greatest symbols of tribal rebellion, Birsa Munda (1875–1900) holds a sacred position in the hearts of millions. Born in the Ulihatu village (present-day Jharkhand), Birsa was from the Munda tribe, a group with a profound cultural and spiritual connection with nature. In the late 19th century, during British colonial times, the tribal population of Chotanagpur was subjected to hard times. Their traditional territories were taken over by landlords and moneylenders, and forest legislation denied their right to farm or harvest forest produce. Missionary pressure and forced conversions also undermined their traditional way of life.

It is against this backdrop of exploitation and cultural decay that Birsa rose as a leader, reformer, and visionary. Educated for a brief period in a missionary school, he cultivated a deep sense of tribal identity as well as colonial oppression. His appeal fused religious awakening with political struggle. He invited everyone to revive the tribal religion, live a chaste life, and turn back from the British colonialists. People started to treat him as a messiah or "Dharti Aba" (Father of the Earth) — a symbol of freedom and hope.

Birsa's movement, termed the Ulgulan (The Great Tumult), started in the late 1890s. It was not merely a revolt against the British Raj but also against the local landlords and missionaries who were exploiting the Adivasis. He brought together different Munda villages and preached about self-rule, equality, and social reform. With him as their leader, the tribal people armed themselves with traditional weapons and fought courageously for their land and rights. The British, fearful of his increasing popularity, made brute attacks to crush the movement.

In 1900, Birsa Munda was arrested and imprisoned by the British. He died under suspicious circumstances in prison at a tender age of 25, but his short life had already made a permanent imprint on India's history. His movement brought about consequential reforms, such as the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act (1908), which acknowledged the rights of tribal land and put limitations on land transfer to non-tribals — a direct outcome of his struggle.

Even now, Birsa Munda's name remains an icon of tribal pride, solidarity, and resistance. His heritage is commemorated annually on Birsa Munda Jayanti (15 November), which is also celebrated as Janjatiya Gaurav Diwas by the Government of India. His name adorns statues, universities, and institutions throughout Jharkhand and other states, symbolizing his dream of freedom and dignity.

Birsa Munda's life teaches us that real independence is not merely political but social, cultural, and spiritual — based upon justice, identity, and self-respect for all native societies.

Jaipal Singh Munda: The Voice in the Parliament

Jaipal Singh Munda (1903–1970) was a visionary leader who made education, sportsmanship, and politics come together to mobilize the cause of India's tribal societies. Hailing from the Chotanagpur plateau in the state of Jharkhand today, Jaipal was a member of the Munda tribe, whose history is full of resisting foreign domination, as witnessed by figures such as Birsa Munda. Contrary to most tribal leaders of his period, Jaipal had access to formal education. He attended Oxford University, where he gained an international vision on leadership, rights, and governance, yet always stayed anchored to the aspirations of his people.

Jaipal Singh Munda is best remembered for standing up for tribal identity and rights in Indian politics. He was a member of the Constituent Assembly of India, where he argued for tribal population safeguards within the Constitution. He underscored autonomy, land rights, and cultural preservation as essential, aware that development could not be achieved at the expense of displacing or marginalizing indigenous groups. His vision represented a blend of modern democratic thinking and tribal ethos, thus enabling him to operate with ease within both traditional and contemporary paradigms of leadership.

Besides politics, Jaipal was also a noted sportsman. He led the Indian field hockey team that won gold at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, which earned him national and international recognition as well as respect. This experience of discipline, collective effort, and leadership carried over to his political life, allowing him to mobilize tribal communities and voice their issues effectively at national forums.

Jaipal Singh Munda also established the Jharkhand Party, a political party committed to the social, economic, and political advancement of Adivasis. On this platform, he fought for the tribal areas' recognition as independent administrative zones so that development and governance would not be left out of involving the voices of the native population. His struggle formed the foundation of what would emerge as the state of Jharkhand in 2000, underscoring his enduring impact on India's politics.

Essentially, Jaipal Singh Munda demonstrated the strength of education, political engagement, and shrewd leadership in advancing tribal well-being. Whereas revolutionaries such as Komaram Bheem and Birsa Munda had used grass-roots mobilization and plain resistance, Jaipal demonstrated that reform too could be implemented within the democratic process. His life reminds us that the Indian struggle for tribal rights had many forms — from revolt to reform — and that representation in the government is a key path towards attaining social justice.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: The Architect of Social Justice

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891–1956) was one of India's most prominent reformers and architects of contemporary social justice. Born to a Dalit (once "untouchable") family in Mhow, Madhya Pradesh, Ambedkar was subjected to discrimination and social ostracism right from the beginning. As the caste system denied him access to good education and social approval, he evolved with a deep insight into inequality, suppression, and the need for structural change. His own struggles were the basis of his life mission: guaranteeing human dignity, equality, and political enfranchisement to India's marginalized groups.

Ambedkar continued his education at home and overseas, receiving degrees in economics, law, and political science from Columbia University and the London School of Economics, among other places. His academic achievements and profound analytical capabilities enabled him to analyze critically the social, economic, and political structures that sustained discrimination. Back in India, he became a leading campaigner for Dalit rights, launching campaigns against caste oppression, untouchability, and social injustice. He underlined the role of education, legal protection, and economic empowerment as means to social emancipation.

Ambedkar's greatest legacy was perhaps his position as Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution. He institutionalized equality before the law, social justice, affirmative action, and safeguards for weaker sections of society through the Constitution, building the basis for an inclusive India. He was also a protagonist of women's rights, labor rights, and religious and cultural freedom of expression. Ambedkar's strategy was fundamentally structural and systemic, and he was interested in long-term structural change rather than quick fixes, unlike modern leaders who think only in terms of protest or grassroots mobilization.

Ambedkar's activism went beyond legal change. In 1956, in a groundbreaking conversion to Buddhism, he renounced caste-based Hindu hierarchy, leading millions of Dalits to seek spiritual and social honor. The message was uncompromising: freedom and justice need both political power and social consciousness.

Dr. Ambedkar's legacy lives on in India and the world today. He represents the intellectual and moral leadership needed to overcome deeply ingrained social hierarchies and establish the rights of marginalized communities. While Komaram Bheem and Birsa Munda rose in rebellion and Jaipal Singh Munda fought for tribal representation in the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar gave a constitutional and legal backup that made India's vision of equality a living reality.

In short, Ambedkar's life is an example of how knowledge, law, and organized activism can be great forces of freedom. His vision is an addition to the struggles of other marginalized activists, showing that the struggle for justice can be of many kinds — from resistance in the forests to reform in the halls of power.

Common Threads Among Them

While Komaram Bheem, Birsa Munda, Jaipal Singh Munda, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar came from various parts of the country, communities, and epochs, their lives expose remarkable parallels in ideals, means, and ends. Common to all their struggles at their very center was a strong faith in justice, dignity, and empowerment for oppressed communities — Adivasis or Dalits.

A strong commonality was also their opposition to exploitation and oppression. Komaram Bheem and Birsa Munda rallied tribal groups to reclaim land, water, and forest rights directly against feudal landlords, colonial regimes, and local rulers. Their resistance was frequently armed and grassroots, indicating the immediacy of protecting livelihoods and culture. Jaipal Singh Munda, who was not a revolutionary in the violent sense, challenged systemic disregard through political activism, representing tribal interests in the Constituent Assembly and later in national politics. Ambedkar, similarly, fought caste-based oppression through legal, constitutional, and educational reforms, emphasizing structural change over rebellion.

The other common characteristic was how much they focused on community mobilization and identity. Bheem and Birsa brought scattered tribal hamlets under a common agenda, enhancing pride in native culture. Jaipal Singh Munda insisted on a political organization to guarantee representation, while Ambedkar promoted social awareness among Dalits, with education and legal empowerment being tools to reclaim identity. All four knew that real change needed awareness along with collective action.

Additionally, all leaders showed great vision and foresight. They recognized that their fight was not merely for transient relief but for lasting social change. Bheem and Birsa fought for permanent rights over natural resources, Jaipal dreamt of self-governing tribal states, and Ambedkar created a constitutional order to safeguard generations from discrimination.

Essentially, the threads that unite these leaders are resistance to repression, fighting for dignity and rights, mobilizing the community, and strategic thinking. Together, they emphasize the plurality of methods in India's quest for justice — illustrating that social change can result from rebellion, political activism, or structural reform, but all point toward the same end: empowerment of the oppressed and the establishment of an equal society.

Their Relevance in Contemporary India

The visions and struggles of Komaram Bheem, Birsa Munda, Jaipal Singh Munda, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar continue to be extremely relevant in present-day India. Even after decades of political freedom, marginalized groups — especially Adivasis and Dalits — remain plagued by land loss, social discrimination, poor education, and weak political representation. The vision of these leaders continues to provide guiding principles in determining the solution to these ongoing problems.

For instance, land and forest rights, central to Bheem and Birsa’s movements, remain contentious today. Large-scale industrial projects, mining, and urban expansion often threaten tribal lands, echoing the very struggles these leaders fought against. The Forest Rights Act of 2006 and various legal safeguards are modern extensions of their vision, emphasizing that tribal communities must have control over resources essential to their survival and culture.

Likewise, Jaipal Singh Munda's emphasis on political representation and self-rule receives echoes in the ongoing demand for tribal self-rule, administrative acknowledgment, and participation in decision-making. The establishment of Jharkhand as an independent state, and ongoing debates regarding tribal councils and rights, underscore the currency of his vision in contemporary governance.

Dr. Ambedkar's own legacy is just as long-lasting. Constitutional safeguards, education and employment reservations, anti-discrimination legislation, and social reform movements all borrow directly from his ideas. His focus on education, social consciousness, and legal empowerment remains a source of inspiration for youth movements, Dalit activism, and policy efforts at equality.

Besides, these leaders together reinforce the imperative of combining social justice and sustainable development. Their existence reminds governments, activists, and citizens alike that development is bound to fail if the rights, culture, and dignity of marginalized people are not safeguarded. During a time of globalization and accelerated industrialization, their visions provide moral direction for balancing advance and equity and inclusion.

In effect, the woes of these four leaders are not ancient history but living lessons. They continue to inform debates on land rights, tribal autonomy, social justice, and constitutional values, attesting to the fact that the quest for equality and dignity is an unfinished journey in contemporary India.

The existence and struggles of Komaram Bheem, Birsa Munda, Jaipal Singh Munda, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar together represent the various trajectories of resistance and change in India's past. Although geographically distant, temporally apart, and differing in their tactics, they had a shared vision of justice, dignity, and empowerment of marginalized sections. Bheem and Birsa battled in the front lines to regain land and resources, Jaipal Singh Munda used political representation to guard tribal rights, and Ambedkar constructed the constitutional and legal architecture to obtain equality for Dalits and other downtrodden classes.

Their memory is a forceful reminder that the fight for social justice and equality continues to this day. Modern India remains inspired by their bravery, vision, and perseverance. Commemorating and remembering their work is not only paying respects to the past but also a call to action — to keep working towards an India in which all people, irrespective of caste, community, or place, can live in freedom, dignity, and possibility.

. . .

References:

- Kiro, Santosh. The Life and Times of Jaipal Singh Munda. New Delhi: Rupa Publications, 2020.

- Komaram Bheem. Wikipedia. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

- Birsa Munda.Wikipedia. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

- Jaipal Singh Munda. Wikipedia. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

- B. R. Ambedkar. Wikipedia. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

- Komaram Bheem: The Voice of the Forests. Telangana Today. Last modified September 30, 2025.

- Birsa Munda: The Tribal Messiah.” The Hindu. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://www.thehindu.com

- Jaipal Singh Munda: The Voice in the Parliament. The Telegraph India. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://www.telegraphindia.com

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: The Architect of Social Justice. The Hindu. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://www.thehindu.com

- Common Threads Among Them.The Hindu. Last modified September 30, 2025. https://www.thehindu.com