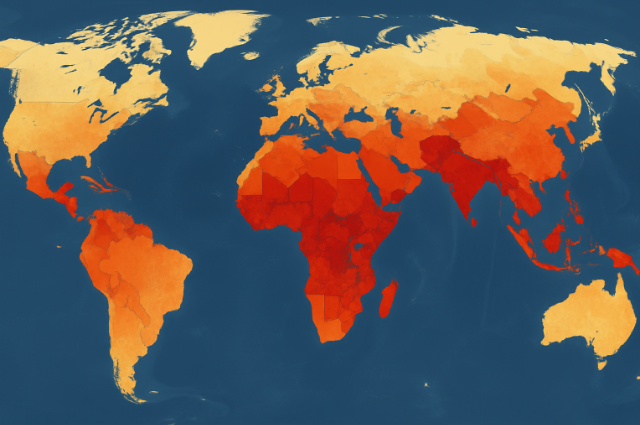

Food security is a deep geographical question, shaped by the interaction between the environment, economy, politics, and society, which creates a very uneven landscape of hunger worldwide. Recent data has emphasized that more than 735 million people in 2025 – 9.1% of the global population – do not have enough food to meet their daily dietary needs. There are major differences; While in developed countries, such as Germany, only 2% of only 2% are unable to use a healthy diet, in hunger hotspots, such as South Sudan and Madagascar, these prices may be more than 90%. These Stark differences are not random, but specific geographical patterns arise from history and processes.

Mapping hunger not only means identifying that people are hungry, but also understanding why these places become hungry spots. Take South Sudan, currently considered one of the most acute hunger areas in the world, where 57% of the population experiences severe food insecurity, and where tens of thousands of people live in famine-like conditions. There are major conflicts with multicolor conflict, economic instability, and large-scale displacement prevent even food production and access. Similarly, places such as Sudan, Palestine, Haiti, and Mali are listed by the UN and the FAO-WFP as the “Hotspots of Supreme Concern”, which is due to conducting food security to the terrible levels due to frequent conflicts, economic falls, and environmental threats.

The technical side of the mapping of this geography has evolved dramatically. Organizations such as the World Food Program (WFP) combine conventional examination-based methods with refined geophysical technologies in which satellite images are provided (geographical information system), and mobile data collection equipment (SMS, interactive voting response) -to monitor the trends of hunger. For example, mobile vulnerability analysis and mapping (VAT) enables real-time tracking in remote or dangerous areas, providing home food consumption, strategies, and significant data to market prices. In Bangladesh, spatial analysis has identified groups of chronic food security in northwestern, mid-south-western and coastal districts, often associated with natural disasters such as poverty, low literacy rate and floods, river erosions and cyclones. These hotspots are dynamic; Some communities face “Monga”, which is a cyclical period of poverty and hunger that repeats every year with agricultural work.

Extensive geographical patterns also explain how climate and the environment interact with social vulnerability to shape hunger. On the Indo-Gangetic land in South Asia, the lack of labor and the use of land are important determinants for food security. In South Africa and on the border of the Sahara, irregular rainfall and recurrent drought triggered crop failure and livestock deaths, and put millions at risk. Urban vs. Rural geographical substances: While rural areas are seen as preparations for chronic poverty and food shortages, rapid urbanization has produced new urban hunger nodes, with a population of increasing marginalization between the costs of growing and unstable work.

Technological progress with mapping food security strengthens more effective interventions. Geophysical methods allow researchers to imagine the flow of food from production to consumption, not only where there is a decline, but also to map bottlenecks and breakdowns in food distribution chains. For example, mapping of food flow can show how resolutions throughout the regions – blockage, market failure, transport blocks, cemeteries. In cities with high development in the global south, the partnership mapping efforts help local communities and decision makers with more accuracy in pinpointing sites of vulnerability.

The combination of Big Data Analytics, Machine Learning, and Pre-Modeling has provided a new level of openness and replication for the crisis prediction model. These data-driven approaches use different sources to model accurate images, weather data, local examination, price indices, and to estimate that the food crisis may occur in the next explosion. This is important for timely intervention, enables agencies to obtain resources before catching famine.

Real-life stories bring the geography of food security to a sharp focus. In Haiti, financial turmoil and gang violence have recently allowed millions of people to meet hunger, with some urban slums, the outskirts of the port, and product now considered an imminent risk to famine. In Myanmar, the ongoing battle and displacement have disturbed the production of rice, a staple for most parts of the country, quickly converted frequent regions into significant hunger hot spots. Meanwhile, the frequent instability of Yemen and the Democratic Republic of Congo continues to push millions into intense food insecurity, complicated by market distribution and import difficulties.

International reactions follow these various geographical challenges. The World Bank has provided $ 45 billion to handle food security in 90 countries, which are aimed at hotspots identified through refined mapping and vulnerability assessment. Nevertheless, humanitarian aid is with its own geographical barrier configuration zone, access limitation, and financing gaps, often means that the help cannot reach those who are most in need.

- Finally, the mapping of global hunger is much more than a technical challenge. It is a human, sociological, and environmental action. The geography of food security not only says which societies are the weakest, but also deep structural reasons: war, poverty, climate change, marginalized and broken food systems. By combining examples of real life, understanding of advanced mapping technologies, and local dynamics, decision makers and support organizations can intervene more accurately, constant, and compassionately, and work towards a future where no place needs to be called a hungry hotspot.

References –