We usually think that only humans can remember us. All those memories, what we say, the lives in the mind and in the soft, invisible space where thoughts and emotions actually stay. But sometimes, when we touch an old sweater, or smell a familiar perfume, or open a box of things from our childhood, something really strange happens. The object actually feels alive. It seems to remember who we truly were, even when we’ve forgotten parts of ourselves. This small and quiet magic raises a deep question. Which is what things remind us of?

The Secret Lives of Things

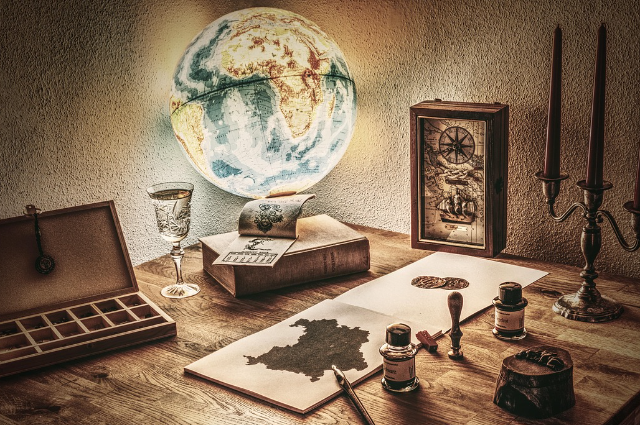

Every object around us holds traces of the people who touched it, used it, or loved it. A chair shaped by years of someone sitting in it. A book whose corners are folded, its pages yellow with time. Even a simple cup, if used every morning, begins to carry a kind of personality, a history written by routine.

When you look closely, the world of objects isn’t lifeless at all. It is full of quiet witnesses. They stand silently, holding the marks of our habits and choices. A ring remembers a marriage. A key remembers the door it once opened. A letter remembers the hand that wrote it.

This isn’t just poetry; it’s also philosophy. Some thinkers, like the French philosopher Bruno Latour, argued that objects have agency, like a small ability to affect the world and shape human lives. A smartphone, for example, doesn’t just sit there. It changes how we think, how we talk, and even how we feel about time. In this way, things live with us and through us.

Memory Without Mind

Can something that cannot think still “remember”? Maybe not in the way we do, not as stories or emotions, but in form, texture, and wear. Every scratch, stain, or faded colour is a kind of memory written in matter. When you see the cracked screen of your old phone, you remember the day you dropped it. But even when you forget, the crack still stays. The object carries that story quietly, waiting for someone to notice again.

Scientists say materials have “memory” too. Metal can remember its shape; fabrics stretch and keep the form of a body; buildings hold the temperature and smell of the people who lived in them. In a way, the physical world keeps a diary we never read fully.

Emotional Echoes

Why do we feel emotional around old objects? Because they don’t only remind us of the past, but they connect us to versions of ourselves that no longer exist. The toy you once played with, the perfume your mother used, the watch your grandfather wore, these are time machines. They let us meet our past selves for a moment.

When we hold an object from someone who has passed away, it can feel almost sacred. The thing becomes a bridge between life and death. It still holds their warmth, their touch, their choices. It’s as if the object keeps a little echo of its soul.

Writers often talk about this. In Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the taste of a small cake, a madeleine, brings back his whole childhood. That tiny object becomes a door through which memory walks in. Maybe that’s what objects do best: they open doors to the invisible.

When We Forget, They Don’t

Our minds are fragile; we forget so easily. But objects don’t. They stay long after we’re gone, holding the marks of our brief time on earth. A dusty piano in an empty house still remembers the music once played. A pair of shoes by the door remembers every road their owner walked.

In that sense, objects are like small tombs of experience. They outlive us and tell stories we no longer can. Maybe that’s their afterlife, and ours too, hidden inside them.

The Beauty of Things That Stay

Thinking this way changes how we see the world. A cracked mug is not just “old," it’s full of memories of mornings, hands, laughter, and silence. A faded photograph is not just paper, but it’s a living moment frozen in matter.

Maybe objects remember us because we leave pieces of ourselves in everything we touch. We move through the world like painters without noticing, leaving colours, fingerprints, and energy behind.

So, when you next hold an old item and feel something deep inside, that mix of sadness and warmth, don’t dismiss it. You are not imagining it. The object really does remember, in its own quiet, wordless way.

Perhaps this is the afterlife we rarely talk about, not in heaven or in memory alone, but in things. The world, after all, keeps everything. We just have to learn how to listen to what objects are trying to say.

References: