Introduction & Background

Electoral integrity is the cornerstone of any democratic system, ensuring that governments derive their legitimacy from the genuine will of the people. In India, the Election Commission (ECI) has traditionally been regarded as the guardian of this integrity, entrusted under Article 324 of the Constitution with the authority to supervise, direct, and control elections to Parliament and state legislatures. Complementing this constitutional mandate is the Representation of the People Act, 1951, which outlines procedures for the conduct of elections and the resolution of disputes.

Despite these safeguards, India’s democratic institutions have periodically faced allegations of irregularities, ranging from voter suppression to manipulation of electoral rolls. The 2024 Lok Sabha elections were no exception, as political leaders from opposition parties accused the ECI of shielding “vote thieves”—a term referring to individuals or groups allegedly engaged in manipulating the electoral process. Rahul Gandhi, for instance, publicly claimed that the poll panel not only tolerated manipulation but actively protected those accused of voter fraud (Economic Times, 2024). Such allegations were amplified by reports of missing voter-roll data in Karnataka, prompting concerns over the Commission’s transparency and accountability (Times of India, 2024).

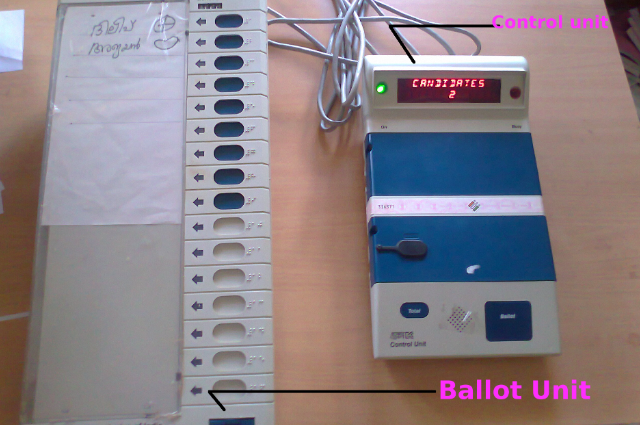

Historically, India’s electoral system has evolved to address fraud and improve public confidence. The transition from paper ballots to Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) marked a significant reform aimed at reducing booth capturing and ballot stuffing. Further innovations, such as the introduction of the Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) system, were implemented to enhance transparency and allow voters to confirm their votes physically. To maintain clean electoral rolls, the National Electoral Roll Purification and Authentication Programme (NERPAP) linked voter identities with Aadhaar numbers, thereby minimizing duplication and fraudulent entries (Wikipedia – NERPAP). While these measures illustrate the institutional robustness of India’s electoral system, the persistence of accusations of shielding vote theft indicates systemic vulnerabilities that merit closer examination.

Safeguards and Mechanisms Against Vote Theft

The Election Commission of India has implemented a range of safeguards designed to protect the electoral process. The introduction of EVMs in the late 20th century significantly curtailed traditional methods of fraud, such as ballot-box stuffing and bogus voting. Analysts have emphasized that EVMs improved election integrity, especially in rural areas and high-risk constituencies (Brookings Institution).

To further bolster confidence, the VVPAT system was introduced, producing a paper trail for each vote cast. In cases of discrepancies between EVM counts and VVPAT slips, the paper record prevails, ensuring verifiability and accountability (Wikipedia – VVPAT). Randomization of EVM deployment through the EVM Management System adds another layer of protection, preventing predictability and reducing the likelihood of tampering (ECI Official – Myth vs Reality).

Additional safeguards include the deployment of polling agents representing each candidate at every booth, ensuring oversight during voting. In cases of disturbances, violence, or suspected manipulation, re-polling provisions allow authorities to rectify irregularities. Furthermore, the maintenance and periodic auditing of voter rolls, as undertaken through programs like NERPAP, aim to minimize fraudulent entries and ensure every eligible voter’s participation. Collectively, these mechanisms form a multi-layered defensive framework designed to maintain the integrity of Indian elections.

Allegations of Shielding & Identified Gaps

Despite these measures, recent controversies highlight significant gaps that have fueled allegations of shielding by the poll panel. Opposition parties have claimed that large-scale manipulations in voter rolls went unaddressed, suggesting either negligence or deliberate complicity. For instance, Rahul Gandhi alleged that the Commission protected high-profile individuals accused of electoral malpractice, refusing to demand accountability (Economic Times, 2024).

Reports from Karnataka underscore this concern. Congress alleged that the ECI withheld critical digital evidence, including IP logs and audit records associated with voter-list changes. This lack of transparency heightened suspicions that the Commission was shielding those involved in manipulation rather than investigating allegations rigorously (Times of India, 2024).

Journalistic accounts have reinforced these criticisms. Frontline characterized the ECI’s conduct during the 2024 elections as ushering India into an “electoral nadir,” citing selective responses to complaints and reluctance to expand VVPAT verification (Frontline, The Hindu, 2024). Such gaps illustrate that while procedural safeguards exist, their implementation is inconsistent, and perceptions of bias or shielding can quickly undermine public confidence.

Other identified weaknesses include the limited verification of VVPAT slips, which is often restricted to a small proportion of polling stations. While this sampling method is practical, it leaves room for undetected discrepancies, especially in tightly contested constituencies (Frontline, The Hindu, 2024). Additionally, the procedural opacity in responding to voter roll grievances and political influence in commissioner appointments raises concerns about the independence and effectiveness of the ECI.

Consequences and Impact on Democracy

Allegations of shielding vote thieves carry profound implications for Indian democracy. At the societal level, such accusations erode public trust, leading citizens to question whether elections are genuinely free and fair. Disenfranchisement—whether through deletion from voter lists or denial of timely grievance redress—represents a direct violation of constitutional rights.

Institutionally, the credibility of elected governments is jeopardized when electoral outcomes are perceived as manipulated. The legitimacy of democratic governance relies not only on actual procedural integrity but also on the perception of fairness. While the introduction of EVMs had previously enhanced the credibility of India’s electoral system (Brookings Institution), current allegations risk undermining decades of institutional trust and electoral legitimacy.

Moreover, repeated controversies can weaken civic engagement, as disillusioned voters may abstain from participating or lose faith in democratic processes. In a country of over a billion citizens, the erosion of confidence in the electoral mechanism threatens both the stability and vibrancy of democracy.

Recommendations & Conclusion

To restore electoral integrity and public trust, a multi-pronged approach is required.

- First, the verification of VVPAT slips should be expanded, particularly in constituencies with close contests. Comprehensive audits, potentially extending to 100% of slips in critical areas, would significantly reduce uncertainty regarding vote counting.

- Second, the ECI must adopt a policy of proactive transparency. Providing access to voter roll audit trails, digital logs, and procedural documentation upon request can bolster credibility and demonstrate institutional accountability. Independent third-party audits, conducted by credible civil society organizations, may further strengthen confidence in electoral outcomes.

- Third, institutional independence must be preserved and enhanced. Appointments of election commissioners should be insulated from political influence through the involvement of the judiciary or bipartisan committees. Ensuring that commissioners cannot be easily shielded from accountability would deter negligence and malpractice.

Finally, public awareness campaigns are crucial. Citizens should be empowered to verify their enrollment, understand their rights, and utilize grievance redressal mechanisms effectively. By combining technological safeguards with civic vigilance and legal accountability, India can mitigate the risk of vote theft and counter perceptions of institutional shielding.

In conclusion, while India’s electoral system is fortified by mechanisms such as EVMs, VVPATs, and legal frameworks, allegations that the poll panel shields vote thieves cannot be ignored. The contradiction between procedural safeguards and observed or alleged gaps highlights an urgent need for reforms. By enhancing transparency, auditing practices, and institutional independence, the ECI can reaffirm its role as the guardian of India’s democratic process, restoring public trust and safeguarding the principle of electoral integrity.

. . .

References:

- Economic Times (2024). Rahul Gandhi alleges EC–BJP vote theft. Link

- Times of India (2024). Vote fraud: Congress accuses the Election Commission of lying. Link

- Frontline, The Hindu (2024). ECI ushers India to its electoral nadir. Link

- Brookings Institution. India’s electoral democracy: How EVMs curb electoral fraud. Link

- Wikipedia. Voter-verified paper audit trail. Link

- Wikipedia. National Electoral Roll Purification and Authentication Programme. Link

- Election Commission of India Official Website. Myth vs Reality – EVM Management System. Link

- Constitution of India, Article 324.

- Representation of the People Act, 1951.