English. It’s everywhere. In India, it sits at the centre of education, governance, and aspiration. And yet, it’s never neutral. I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately - about how a language, just words strung together, can carry so much power.

Growing up, English was a status symbol. In my school, kids who spoke English fluently were often treated differently. Teachers praised them, classmates admired them, and parents quietly nodded approvingly. My own family didn’t emphasise English in early childhood, but I saw its magic. Those who wielded it confidently seemed to move faster, get ahead more easily, as if words alone could bend the world in their favour. And maybe they could.

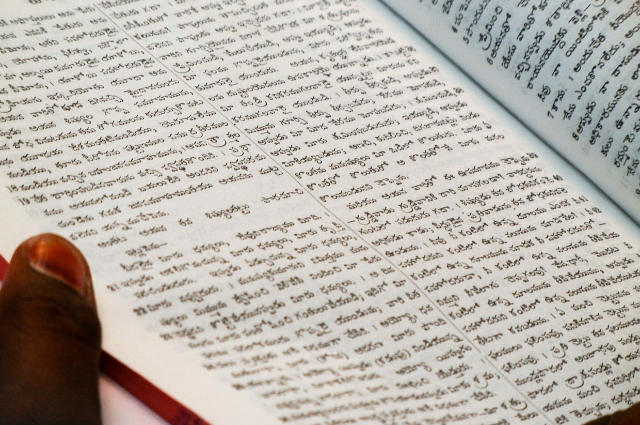

It’s strange to realise that English in India is a colonial inheritance, yet it has been internalised as a ladder to opportunity. Back in the days of the British Raj, English was a tool of control - a way to separate rulers from the ruled. Lord Macaulay, famously, wanted “a class of people, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste and intellect.” And that class? It existed. It still echoes today in private schools, coaching centres, law colleges, and corporate offices. English is prestige. English is powerful. English is a kind of currency.

And yet, there’s a paradox. English is both inclusive and exclusive. It allows you access to global literature, international jobs, and higher studies abroad. It opens doors that might otherwise remain shut. But it also shuts out millions who don’t grow up speaking it. I think about rural India, small towns, and children in underfunded schools. Many of them are brilliant, creative, and capable. But if your accent, your grammar, or your vocabulary isn’t polished in English, suddenly the world measures your worth differently. Meritocracy seems fair only if you are fluent. Otherwise, the game was stacked from the start.

I’ve seen this in classrooms and in my own life. I remember joining NALSAR and feeling utterly out of place sometimes - not because I didn’t understand law, but because the speed of conversations, the references, the jokes, and the subtle wordplay in English made me hesitate. It wasn’t about intelligence. It was about the unspoken hierarchy of language. And I hated that I had to struggle with something that wasn’t inherently related to my mind, my reasoning, or my capacity.

English has also become aspirational in India. Parents enroll kids in English-medium schools, tutors push vocabulary flashcards, and everyone dreams of mastering a language they didn’t grow up with. The irony is, mastery often doesn’t come from love but from fear of being excluded. I’ve met brilliant students who hate English, who cringe at reading it, but they endure it because their future depends on it. And I understand. I’ve been there.

Policy plays a role, too. The Official Languages Act of 1963, for instance, makes English a permanent associate official language alongside Hindi. This is practical for administration, yes, but it also entrenches a bilingual elite. If you can function in English, doors open; if not, your voice is quieter, your participation limited. English mediates power in India - politically, socially, and economically. It’s subtle but pervasive.

What about regional languages? There’s a constant tension. Politicians champion Hindi, regional governments support local languages, and English is sometimes seen as a threat to cultural identity. Yet, in urban India, English survives as the lingua franca of aspiration. Code-switching—Hinglish, Manglish, Tanglish—is everywhere. People mix English with their mother tongue seamlessly. But underneath the fun hybridity is still hierarchy. English words carry more weight, sound more “official,” more educated.

I’ve come to think that English in India is not just a language. It’s a mirror reflecting class, privilege, colonial history, ambition, and exclusion all at once. And it’s personal. Because you feel it in everyday interactions—the casual judgment when your accent slips, the way your ideas are valued differently based on your grammar, the invisible barrier between you and the “fluent” few.

Yet, English also allows for subversion. Writers, activists, poets, lawyers, bloggers - they take English and make it their own. They bend it, play with it, localise it, and in doing so, reclaim some power. There is space to disrupt the hierarchy even in the language itself. Perhaps that is the only way it remains bearable: not as a rigid gatekeeper but as a flexible tool for expression.

At the end of the day, English in India is about opportunity - but it’s also about inequality. It’s about who gets heard and who doesn’t. It’s about the pressure to perform, to conform, to sound “correct.” And while it has undeniably expanded access for many, it continues to alienate and exclude in subtle ways. Understanding this is critical if we ever hope to move toward a society where knowledge, talent, and intellect are not measured by fluency in a colonial language.

And so I write this as someone who lives in both worlds - privileged enough to speak English well, aware enough to know its politics, conflicted enough to question its place in my identity. English has shaped my life, for better and worse. It has allowed me opportunities, yet it has imposed pressures. It has connected me to global thought, yet reminded me that not everyone has the same starting line.

English is everywhere in India. And it is never neutral.

References

- The Politics of Language: English Between Colonial Control and Postcolonial Identity in India – Sushil Subham Rout

- English Language Education in India: How Aspirations for Social Mobility Shape Pedagogy – EPW Engage

- Official Languages Act, 1963 – Wikipedia

- English Medium Education in India: The Neoliberal Legacy and Challenges – PDF