Flames in the Sky

On a silent night in the 12th century, the horizon above Bihar glowed not with the light of dawn but with a dreadful inferno. The flames of Nalanda’s library, the Dharmaganja, pierced the sky, devouring wooden shelves and delicate palm-leaf manuscripts. The air grew heavy with the scent of ink and burning parchment, as centuries of accumulated wisdom turned to ash. For days and weeks, the fire refused to die, and legend whispers that it burned for months, fuelled by an ocean of knowledge.

Yet this was no ordinary library. Nalanda University, the proud guardian of Dharmaganja, had been a living monument to the human spirit of inquiry. Scholars, seekers, and pilgrims from distant lands once walked through its gates, convinced that within its walls resided not just books, but the essence of civilization itself. The tragedy of its destruction still echoes as one of the greatest cultural wounds in human history. The story of Nalanda is not merely about a university lost to fire; it is about the fragility of human achievements and the eternal hunger for wisdom that no blaze can extinguish.

Nalanda University: A Cradle of Knowledge

Long before Oxford’s stone towers or Cambridge’s ivy walls rose in Europe, Nalanda flourished in the fertile plains of Magadha. Established in the 5th century CE under the Gupta emperor Kumaragupta, it was the world’s first great residential university. Here, knowledge was not confined to classrooms; it was lived, breathed, and shared across courtyards, monasteries, and lecture halls. Nearly 10,000 students and 2,000 teachers formed a vibrant community where learning shaped daily existence.

What made Nalanda extraordinary was its magnetism. Pilgrims came from Tibet and China, monks sailed from Korea and Sri Lanka, and even scholars from Java crossed seas to reach its gates. They found a curriculum vast in scope: Buddhist philosophy in its many schools, logic and debate sharpened like swords, mathematics and astronomy that mapped the skies, medicine that healed bodies, and grammar that refined thought itself. Nalanda was not just a university; it was a microcosm of the intellectual world, a cradle where diverse traditions were nurtured and knowledge itself was the common language. It earned, rightly, the title of the “Oxford and Cambridge of the ancient world,” centuries before Europe dreamt of such institutions.

Dharmaganja: The Intellectual Heart

If Nalanda was the body of learning, Dharmaganja was its beating heart. Rising in three magnificent structures, Ratnasagara (“Sea of Jewels”), Ratnadadhi (“Ocean of Treasures”), and Ratnaranjaka (“Adorned with Gems”), the library was more than stone and mortar. It was a sanctuary of thought, where shelves groaned under the weight of palm-leaf manuscripts, each inscribed with delicate scripts that held the wisdom of ages.

Here lay treasures beyond price: the sacred texts of Mahayana, Hinayana, and Vajrayana Buddhism; the rhythmic verses of the Vedas and Upanishads; works of Ayurveda detailing cures and surgeries; astronomical calculations mapping the stars; grammar that structured language itself; and poetry that captured the soul of civilizations. Dharmaganja was not just a storehouse but a living organism. Monks debated across its halls, translating Sanskrit into Chinese, refining commentaries, and ensuring ideas travelled beyond India’s borders.

The library was, in truth, Asia’s intellectual pulse. To step into its chambers was to step into a world where cultures met, philosophies clashed, and wisdom was reborn. Its very existence embodied the idea that knowledge was not bound by geography or religion; it was humanity’s shared inheritance.

Xuanzang and Yijing: Voices of Witness

The grandeur of Nalanda is not a myth carried on rumour; it is a reality etched in the writings of those who saw it with their own eyes. Among them, Xuanzang, the celebrated Chinese pilgrim of the 7th century CE, offers perhaps the most vivid testimony. He arrived at Nalanda as a seeker and stayed for years, immersing himself in the rigorous disciplines taught there. His accounts describe lecture halls filled with thousands of students engaged in debates so precise that a misplaced word could cost a scholar his reputation. Xuanzang returned to China with more than manuscripts; he carried the spirit of Nalanda, translating texts that shaped East Asian Buddhism for centuries.

Another pilgrim, Yijing, arrived not long after and confirmed the brilliance of this academic haven. He wrote of monks who mastered not only Buddhist scriptures but also medicine, grammar, and logic. He marvelled at the system of translation that allowed ideas to leap across languages, ensuring Nalanda’s wisdom echoed far beyond India’s borders. Through the words of Xuanzang and Yijing, Nalanda still speaks to us today, not as a forgotten ruin but as a vibrant centre of global learning.

Knowledge Without Borders

Nalanda was never just an Indian institution; it was a meeting ground for civilizations. Within its walls, knowledge flowed freely across frontiers, unshackled by geography or creed. Students from Tibet carried home Buddhist logic sharpened through debates. Chinese pilgrims bore sacred texts and treatises on astronomy. Monks from Korea, Sri Lanka, and Java carried fragments of philosophy and medicine that would influence their homelands.

What makes Nalanda remarkable is not only what it taught, but how it connected cultures. Buddhist philosophy was transmitted alongside practical sciences, Ayurveda travelled with meditation, astronomy with ritual, and grammar with poetry. This interweaving of ideas created a shared intellectual fabric across Asia. Nalanda was, in truth, the heartbeat of a global classroom centuries before Europe dreamed of its universities. If Bologna and Oxford stand today as pillars of the Western academic tradition, Nalanda stood far earlier as Asia’s lighthouse of knowledge, a model of intellectual exchange that remains unsurpassed in spirit.

The Fire That Consumed Wisdom

But even the brightest lamp can be extinguished. Around 1193 CE, Bakhtiyar Khilji, a Turkic invader, swept through Bihar with his army. Nalanda, once revered as a sanctuary of learning, was reduced to rubble and smoke. The monks, unarmed and defenceless, were slaughtered, their voices silenced mid-chant. The jewel of Asia’s intellect fell to the sword.

It was the library, Dharmaganja, that suffered the cruellest fate. When Khilji’s men set their towers ablaze, the flames leapt hungrily from one hall to another, consuming palm-leaf manuscripts and birch-bark scrolls by the millions. Chroniclers say the fire raged for months, refusing to die, as though the very knowledge resisted its end. Imagine the stars and galaxies mapped in its charts, the verses of forgotten poets, the cures of ancient physicians, all vanishing in smoke.

This was not just a building destroyed; it was centuries of accumulated human thought erased in a single act of violence. The loss of Dharmaganja was more than India’s tragedy; it was the world’s treasury loss. It reminds us of how fragile knowledge is, and how easily the arrogance of swords can silence the whispers of wisdom.

Centuries of Silence

When the flames finally died and the ruins cooled, Nalanda fell into a silence more haunting than fire. What had once been the bustling capital of knowledge was reduced to smouldering debris, its courtyards empty, its libraries hollow. Monastic chanting ceased; the debates that once sharpened minds were no more. India, which had proudly given wisdom to the world, now bore the wound of its greatest intellectual loss.

The decline of Buddhist learning in India quickened after Nalanda’s fall. The scholars who survived scattered to distant lands, Tibet, China, and Southeast Asia, and became the new guardians of Nalanda’s spirit. There, Buddhism thrived, enriched by the seeds once sown in Bihar’s fertile soil. But in India, the golden flame dimmed. Generations passed without the rigor and brilliance that had defined Nalanda. One cannot help but wonder: if the Great Library had survived, what discoveries, what philosophies, what medicines might have changed the course of history? The silence of Nalanda is a silence of lost possibilities.

A Phoenix Rising

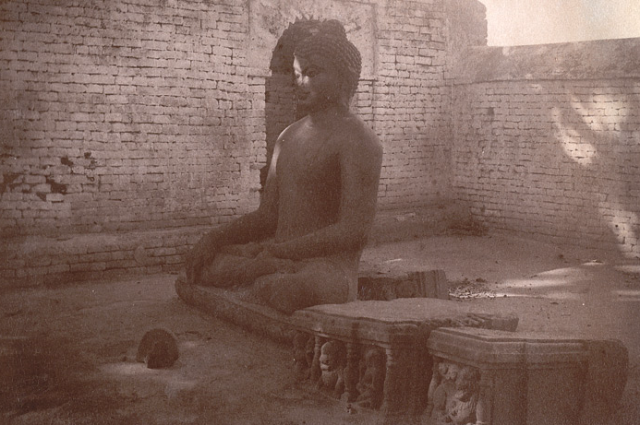

Yet ruins do not remain silent forever. In the 19th century, when archaeologists began to unearth Nalanda’s remains, the earth revealed what memory had hidden. Crumbling brick monasteries, sculpted stairways, and broken idols whispered stories of a forgotten empire of thought. Scholars pieced together its history from Xuanzang’s and Yijing’s writings, and slowly, Nalanda returned to the world’s imagination.

In 2016, UNESCO declared Nalanda a World Heritage Site, sealing its place not as a forgotten ruin, but as a universal treasure. Even more symbolic was the establishment of the New Nalanda University in Rajgir during the 2010s, built with international collaboration. Though no modern campus can truly revive the spirit of Dharmaganja, the attempt is meaningful. It is an acknowledgment that the light of Nalanda still matters, that humanity owes itself a revival of its intellectual legacy. Like a phoenix rising from its ashes, Nalanda reminds us that knowledge, though it may burn, is never fully destroyed.

From Ashes to Inspiration

The story of Nalanda does not end with fire; it lingers in memory like an ember refusing to die. Those flames that once consumed Dharmaganja were not only symbols of destruction but also of rebirth for fire, after all, clear the ground for new beginnings. Nalanda’s ruins stand as witnesses to both human brilliance and human folly: the brilliance of a civilization that believed knowledge belonged to all, and the folly of those who thought wisdom could be silenced by swords and flames. What Nalanda teaches us today is as urgent as it was a thousand years ago that knowledge is fragile, yet resilient. Libraries can burn, but the hunger for truth endures. Scrolls may vanish, but ideas find new soil. The revival of Nalanda in the modern age is proof that wisdom cannot be buried forever. It rises, generation after generation, carried by those who refuse to forget.

To remember Nalanda’s Great Library is not merely to mourn what was lost, but to honour the eternal quest it represented, the quest for understanding, for dialogue, for light in a world too often shadowed by ignorance. In every book opened, every idea shared, the spirit of Nalanda lives again. The fire that burned for months now glows within us as inspiration, urging us never to let knowledge fall to silence again.