A Lamp in the Ruins: The World After 1857

After 1857, Delhi was left in quiet, its palaces destroyed, its libraries looted, and its Muslim leaders turned from influential people to suspects. Authority, knowledge systems, and moral confidence all collapsed during the rebellion, which was not only a political disaster but also an epistemic rupture. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan entered this emptiness. He was not content to mourn; he refused both romantic nostalgia and paralysing despair. Instead, he posed a sharper and unsettling question: could a community survive if it rejected the very instruments of modernity?

Sir Syed’s response was radical in method. He reframed survival as a problem of knowledge, not simply politics. The path forward lay in appropriating new epistemologies English language, Western sciences, and modern historiography and translating them into the Muslim lifeworld. This was no capitulation but a strategy of power: “We must acquire Western knowledge,” he wrote, “if we wish to regain our lost position.” Education, not grievance, became his diagnosis of decline.

When viewed in this context, his endeavours in the establishment of the Scientific Society in Ghazipur, the publication Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq, and ultimately the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College, were more akin to a blueprint for the restoration of civilisation than acts of altruism. These establishments represented a bold assertion: that faith and reason were not rivals but rather possible allies in preserving culture. In addition to building schools, Sir Syed also built an intellectual infrastructure that allowed for the restoration of dignity and the transformation of the ashes of 1857 into the cornerstones of rebirth. In ruins, he lit a lamp, and that lamp was knowledge.

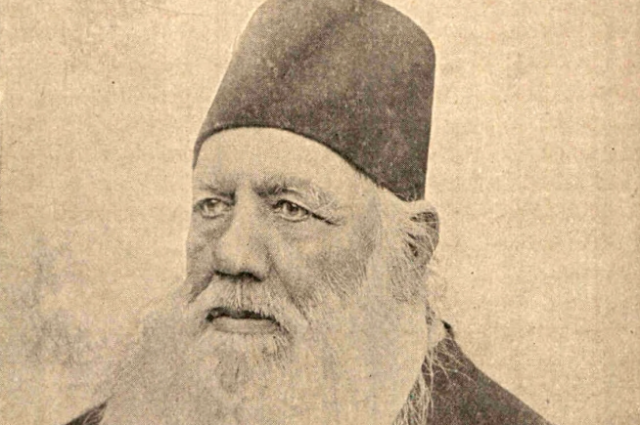

From Courtier to Visionary: Sir Syed’s Awakening

The early years of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan's life took place during the decline of the Mughal empire, when social standing was determined by Persian letters, Urdu sophistication, and courtly service. He was well-versed in the old-world idioms as a scholar and judicial official. Yet, within those very corridors of administration, he encountered the starkly different knowledge systems of the British new sciences, bureaucratic rationality, and a language of law rooted in empiricism. This exposure did not produce imitation but provoked transformation. From a loyal courtier, he became a visionary who sought to reorganise his community's intellectual foundations.

This change was gradual and influenced by a number of shocks rather than a single epiphany. Following the 1857 uprising and the subsequent violent retaliation, Sir Syed became convinced that the decline of Muslims could not be entirely ascribed to political defeat. It was, more fundamentally, a collapse of intellectual preparedness. In his famous Asbāb-e-Baghāvat-e-Hind (Causes of the Indian Revolt), he refused to reduce catastrophe to mere lamentation; instead, he dissected causes with forensic detachment. Why had a community once entrusted with administration and scholarship fallen to the margins? His answer was uncompromising: the failure lay in educational stagnation. “Ignorance,” he wrote, “has been our greatest misfortune.”

This conviction generated practical experiments. The Scientific Society of Ghazipur, founded in 1864, translated Western works into accessible Urdu, attempting to democratize modern knowledge. Journals such as Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq aimed to reshape habits of thought, arguing that English and modern science did not erode religious identity but rather fortified the community’s capacity to survive within new political and social structures. Education, for Sir Syed, was not rhetoric; it was a strategy, a method of rebuilding dignity and restoring Muslims to relevance in a changing India.

Seen closely, his awakening exemplifies practical idealism. He didn't embrace radical disruption or give up on tradition. He showed that faith and reason could coexist for the sake of societal survival by redefining heritage as a means of renewal. Out of grief, he fashioned institutions; out of personal reflection, he built a public program. That synthesis tradition reimagined through modern knowledge is the enduring core of his legacy.

Between Mosque and Laboratory: Reconciling Faith and Reason

Sir Syed’s true originality lay not only in establishing institutions but in rethinking the intellectual contract between revelation and reason. He boldly asserted that divine truth could never conflict with natural truth at a time when many Muslim scholars regarded Western science with suspicion. If the universe is God's creation and the Qur'an is God's word, then sincere investigation of one must coexist with the study of the other.

This belief led him down a bold and contentious path. He aimed to demonstrate that rational exegesis and comparative analysis could strengthen rather than undermine Islam in Tabyīn al-Kalām, his commentary on the Bible. He maintained that the two lenses of reason and observable fact should be used to interpret the verses of the Qur'an. Where traditionalists feared this rationalism diluted faith, Sir Syed insisted it purified it. He famously said, "The Word of God cannot be opposed to the Work of God." He saw blindly rejecting science as negligence rather than piety.

He saw the laboratory and the mosque as parallel sanctuaries of wonder, one based on creation and the other on scripture, rather than rivals. His defence of mathematics, astronomy, and medicine as essential to Muslim rejuvenation was made possible by this synthesis. He reframed knowledge itself as devotion by portraying such disciplines as acts of reverence rather than as challenges to tradition. As expected, there was strong opposition. Fatwas condemning him as misguided were issued by Indian theologians and jurists; some charged him with modifying Islam to appease colonial overlords. Yet Sir Syed held firm. He maintained that his allegiance was to truth rather than to rulers and that truth required Muslims to maintain their spiritual depth while embracing the spirit of science.

Sir Syed is revealed as a philosopher of knowledge rather than just a pragmatist by this delicate balancing act. He was creating a modernity that was uniquely Muslim, treating reason as a map and faith as a compass. In this vision lies his enduring radicalism: the courage to stand at the threshold of mosque and laboratory, insisting that they illuminate, rather than extinguish, one another.

The Aligarh Experiment: Building an Institution for the Future

If Sir Syed’s philosophy was a lamp, the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College (founded in 1875) was the structure that sheltered its flame. More than a cluster of classrooms, it was conceived as a laboratory for a new Muslim identity, an identity that could converse with scripture while mastering science, that could move from mosque to laboratory without contradiction. Sir Syed saw in Aligarh not only an educational institution but a civilizational project: the reconstruction of Muslim intellectual life after the ruins of 1857.

The Aligarh Experiment grew from his conviction that translations and scattered societies were insufficient. The Scientific Society’s efforts to render Western texts into Urdu had seeded curiosity, but genuine transformation required a generation trained to inhabit two worlds at once: the heritage of Islam and the structures of British modernity. “The College,” he declared, “will be the arsenal for the intellectual battles of our future.” Modelled partly on Oxford and Cambridge, yet adjusted to Indian realities, the College fused the ideals of British pedagogy with Muslim cultural pride.

This dual goal was reflected in its curriculum. Students studied English literature, mathematics, modern science, philosophy, and Islamic theology in addition to Arabic and Urdu poetry. The actual physical surroundings were symbolic, with gothic arches rising alongside domes, laboratories next to mosques, and libraries encircling prayer halls. Every detail demonstrated that, to survive, Muslims had to embrace modern knowledge rather than retreat.

Yet Aligarh was never reducible to classrooms or examinations. It was a training ground for a new Muslim intelligentsia, young men who could serve as intermediaries between the empire and the community. In the absence of such leaders, Sir Syed feared that Muslims would remain excluded from the workforce and from politics. In order to develop a cadre capable of navigating modern power while adhering to their principles, he sought empowerment rather than imitation.

Opposition was fierce. Orthodox scholars accused him of corrupting youth, of importing infidel learning into sacred spaces. Later, nationalist critics charged that Aligarh produced loyalists rather than rebels, collaborators rather than revolutionaries. Sir Syed, however, remained unshaken. To him, the stakes were existential: “To shun modern education,” he warned, “is to dig the grave of our community with our own hands.” His argument was never subservience but survival, an insistence that Muslims could only claim dignity in a colonial order by mastering its epistemic codes.

Thus, the Aligarh College was more than just an establishment; it was a historical gamble. The Aligarh Movement, which impacted Muslim politics, identity, and intellectual currents throughout South Asia, was sown in its classrooms by Sir Syed. If 1857 had signified collapse, Aligarh represented counter-architecture, a fortress built not of stone walls but of cultivated minds. Its graduates carried forward the paradox of Sir Syed’s legacy: loyal servants of the empire to some, visionary builders of Muslim modernity to others. Either way, the flame kindled at Aligarh illuminated the subcontinent long after its founder’s death.

Resistance and Rebuttal: Facing Orthodoxy and Nationalists

If the Aligarh Experiment was Sir Syed’s lamp, its light did not shine without shadow. Critics condemned its founder as a collaborator or a heretic for each student who was moved by its promise. Two powerful factions formed the basis of the opposition: the burgeoning nationalists, who charged him with undermining the fight for independence, and the orthodox ulama, who feared he was weakening Islam.

From the orthodox side, the criticism was relentless. Sir Syed’s rationalist hermeneutics, his insistence that revelation must accord with reason, was deemed subversive. His engagement with the Bible in Tabyīn al-Kalām and his readiness to converse with Christian theology provoked fatwas that branded him as dangerously astray. To traditionalists, he was no reformer but an innovator (bid‘ati), luring Muslims away from ancestral faith. Yet Sir Syed refused to yield. His rebuttal was strategic and rooted in scripture itself. The Qur’an, he argued, repeatedly enjoins believers to reflect upon creation, to think, and to inquire. To reject science, therefore, was not fidelity but betrayal. “God has given us eyes to see His works, minds to understand them, and hearts to believe in Him,” he wrote; to close those faculties was to turn away from divine command.

The second front of opposition came from Indian nationalists. The early Indian National Congress and its sympathizers accused Sir Syed of sowing division by discouraging Muslims from mass politics. His repeated warnings that Muslims were not yet educationally prepared for representative democracy were interpreted as cowardice or complicity with colonial rulers. Later historians echoed this charge, claiming Aligarh produced loyalists more than revolutionaries.

Sir Syed’s response here was sharper. Politics without preparation, he argued, was reckless. A community bereft of modern knowledge would enter politics as dependents rather than leaders, vulnerable to both majority dominance and colonial suspicion. His creed was simple: education first, then politics. He did not dismiss nationalism but reframed its timing. To rush into political agitation, in his view, was to risk communal annihilation. Only through learning could Muslims reclaim dignity and negotiate with confidence in the public sphere.

This refusal to bend, whether before fatwas or nationalist reproach, revealed the steel beneath his pragmatism. He was viewed by his followers as a wise sage who put survival before praise. He was viewed by his critics as a collaborator or a heretic. His uniqueness, however, is most evident in his readiness to put up with criticism. Sir Syed was not serving the empire nor placating orthodoxy; he was securing the intellectual foundations of a community’s future. In standing amid storms, he preserved the lamp of knowledge so it could not be extinguished.

Survival Philosophy: Political Vision, Pragmatism, and Loyalty

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan's political beliefs have all too frequently been reduced to "loyalty to the British." Read that way, he appears timid or complicit, a supplicant before power. Yet such a view misses the deeper logic of his politics. For Sir Syed, loyalty was a survival philosophy developed in the furnace of 1857, not theology. His tactful deference was intended to buy the time and space required for the intellectual renewal that he believed was essential to Muslim honour.

He understood power as inseparable from knowledge. The colonial state rewarded administrative competence and distrusted communities unable to speak its idiom of law and governance. Thus, he urged Muslims to pursue English education, not to appease the empire but to accumulate cultural and social capital. “Do not waste your energies in fruitless opposition,” he cautioned; “strengthen yourselves with knowledge, and power will come.” Accommodation, then, was not servility but foresight: establish educational footholds first, so that future generations could bargain from strength. His was a politics of preparation rather than premature agitation.

This strategic patience shaped his initiatives. Established in 1886, the Muhammadan Educational Conference was more of a civic organisation than a political party, to revive the neighbourhood by disseminating curricula and schools. In order to create networks of influence based on education rather than agitation, he courted Muslim nobles, Hindu patrons, and princely donors. According to academics, this civic endeavour helped Indian Muslims develop a new public culture that is focused on knowledge, decency, and institutional proficiency.

Critics, both then and later, charged that this program unintentionally encouraged separatism, for Aligarh’s graduates became articulate in a distinct Muslim political idiom. This, however, is only a partial truth. Education inevitably furnishes the language of politics, but how that language is used depends on historical context. To equate Sir Syed’s educational philosophy with a blueprint for separatism is to mistake his means for later ends. His immediate end was survival through knowledge; the later uses of Aligarh’s legacy were the adaptations of successors.

Viewed philosophically, Sir Syed’s politics resembled Stoic prudence, accepting limits, working within them, and transmuting constraint into capacity. It was also a form of ethical realism: the recognition that moral courage may sometimes require postponing confrontation until one is prepared to prevail. That realism unsettles simplistic judgments but reveals a thinker intent on securing conditions for genuine agency. His legacy, therefore, is not confined to Aligarh’s walls. It is a lesson in political wisdom: build competence first, and only then contest power.

Beyond the Gates: The Aligarh Generation and New Publics

A new class, a new imagination, and a new rhythm in the cultural life of Indian Muslims were released when the gates of Aligarh opened, in addition to graduates. These young men became ambassadors of a hybrid worldview, not just holders of degrees. They could cite Newton in the morning and recite Rumi by night. They could draft legal petitions in English, yet deliver a Friday khutbah in Urdu. This dual fluency allowed them to move between mosque and court, madrasa and laboratory, translating across worlds that rarely touched.

The Aligarh Generation became a living bridge: between rulers and ruled, between tradition and modernity, between faith and reason. They carried Sir Syed's legacy into the growing print industry, courts, and schools. While debate societies in Aligarh honed arguments that would later influence nationalist and communal politics, newspapers like Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq provided a platform for rationalist and reformist Muslim thought. They had an impact on public life and created new terms for civic and intellectual engagement outside of the classroom.

But this new identity carried tensions. To orthodox critics, these men were dangerously “half-Westernized,” their minds corrupted by colonial science. To radical nationalists, they were cautious reformers who lacked the fire of revolution. Yet to their own community, they embodied a subtler kind of power: the power of translation. Translation was their weapon. They translated Muslim concerns into idioms that colonial officials could understand while also converting the abstractions of contemporary science into language that Muslims trained in madrasas could understand. They brought together worlds that might have remained apart through this act of mediation.

The outcomes were contradictory. On one hand, Aligarh nurtured loyalist bureaucrats who served the Raj. On the other hand, it inspired the fiery politicians of the twentieth century who demanded independence and, in time, partition. The same training produced servants of the empire and architects of new nations. This dual legacy reveals Sir Syed’s true achievement: he did not manufacture a fixed ideology, but rather capacity. Once capacity is born, it escapes the designs of its founder and adapts to the pressures of history.

Thus, the Aligarh Generation was more than a social elite; it constituted a new Muslim public. They were not relics of decline but actors of modernity. They did not merely accommodate colonial modernity; they reshaped it, bending its tools for their own purposes. In this newly emergent intellectual culture, the echo of Sir Syed’s voice endured—not as command, but as a spark.

Legacy and Contested Memory: Sir Syed in Postcolonial Eyes

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s afterlife in South Asian memory is less a settled monument than a contested battlefield of interpretation. To some, he remains a prophet of modernity—the man who rescued Muslim dignity through education. Others claim that he was the reluctant creator of a political theory that later evolved into rhetoric for separatism. While there are some partial truths in both interpretations, neither fully explains the subtleties. His legacy is disputed because his struggles with identity, power, and knowledge have not been resolved over time.

Academics have traced how Aligarh’s bilingual, bicultural pedagogy produced capacities that long outlived his intentions. David Lelyveld has shown that the “Aligarh Generation” was not merely servants of empire but creators of a new Muslim public sphere. They mediated between rulers and ruled, but in doing so, they also developed a political vocabulary that could be repurposed in the nationalist and communal debates of the twentieth century. In this sense, Aligarh was not a factory of ideology but of capacity: it trained minds whose uses history would later determine.

Postcolonial critics take a sterner view. Mushirul Hasan and Francis Robinson argue that Sir Syed’s pragmatism, though rational in his own context, laid the groundwork for exclusivist politics later. They caution against simplistic teleologies that portray him as the direct father of partition, yet they insist his reformist institutions inevitably created habits, vocabularies, and elites that shaped subsequent trajectories. The point is subtle but crucial: institutions rarely bind destiny, but they do shape its possibilities.

This plurality is reflected in current discussions. Through festivities that emphasise pluralism, reason, and civic advancement, he is presented as a nation-builder in Aligarh. His critics, on the other hand, draw attention to his elite biases, his reluctance to participate in democratic politics, and his intermittent communal distinctions. The man who had the idea for a "Muslim Cambridge" is therefore either hailed as a visionary moderniser or condemned as an imperialist collaborator, causing public memory to shift. This plurality of remembrance, however, might be his greatest legacy in and of itself, since modernity always yields contradictory inheritances.

Perhaps the most enduring verdict is also the most practical. Whether we call him liberal or conservative, loyalist or reformer, Sir Syed’s injunction remains luminous: “Do not show the face of Islam to the world as full of ignorance and narrow-mindedness. Acquire knowledge, because knowledge alone is the source of dignity and power.” In today’s debates on secular education, scientific temper, and minority uplift, his experiment at Aligarh offers both warning and promise. Institutions can transform communities, but they cannot dictate destiny. To read Sir Syed, then, is to practice civic intelligence rather than partisan judgment.

Conclusion: The Lamp That Refuses to Die

Men who follow the crowd and those who walk alone with a lamp are the two types of men that history remembers. The second type included Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan belonged to the second kind. He neither sought the applause of orthodoxy nor echoed nationalist slogans for comfort. Instead, he lit a fragile lamp -education- and guarded it with the stubbornness of faith, even when that stubbornness looked like madness to his critics. That lamp became Aligarh, and from its glow arose a generation able to think, speak, and lead in the language of their time. It is tempting to reduce his legacy into narrow categories: collaborator or reformer, modernist or conservative, hero or heretic. But such binaries flatten his depth. His politics was not servility but survival; his rationalism was not unbelief but obedience to God’s command to seek knowledge. He accepted being misunderstood in his own century so that his people might not be voiceless in the next. To dismiss this as cowardice is to miss the bravery of patience.

Today, when education is again contested as privilege or burden, when societies fracture over identity, Sir Syed’s conviction that knowledge is dignity sounds prophetic. He knew that without institutions, a people remain shadows; with them, they become actors in history. His warning that neglect of modern learning would mean permanent subordination is no less urgent for our present. To treat knowledge as optional is to choose silence in history’s court.

And yet, his lamp was never meant for Muslims alone. Aligarh was conceived as a bridge, not a wall; a place where communities could step into modernity together. The fact that subsequent generations directed their flame in different directions, pluralism for some and separatism for others, only serves to highlight how alive his experiment was. Education increases possibilities rather than dictating fate.

So, let's go back to the original image. In an age of ruins, Sir Syed placed a lamp in his people’s hands. It flickered in storms of fatwas and nationalist condemnation, yet it refused to die. It still illuminates our debates on education, identity, and survival. And as long as those debates endure, the man who lit it walks with us.

. . .

References:

Primary Sources

- Khan, Sir Syed Ahmad. Asbāb-e-Baghāvat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian Revolt). Translated by Asok Sen.. Delhi: Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli, 1999.

- Tabyīn al-Kalām: A Commentary on the Bible. Agra, 1862–65.

- Essays on the Life of Mohammed and Subjects Subsidiary Therein. London: Allen & Co., 1870.

- . Quoted in Shan Mohammad, ed. Writings and Speeches of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Bombay: Nachiketa Publications, 1972.

Secondary Sources

- Hasan, Mushirul. A Moral Reckoning: Muslim Intellectuals in Nineteenth-Century Delhi. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Lelyveld, David. Aligarh’s First Generation: Muslim Solidarity in British India. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

- Metcalf, Barbara D. Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Minault, Gail. Secluded Scholars: Women’s Education and Muslim Social Reform in Colonial India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

- Robinson, Francis. Separatism Among Indian Muslims: The Politics of the United Provinces’ Muslims, 1860–1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974.

- Troll, Christian W. Sayyid Ahmad Khan: A Reinterpretation of Muslim Theology. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing, 1978.