In India, bureaucracy can delay your work, deny your rights, and sometimes erase you. For Lal Bihari, it did something far worse. It killed him on paper while he was very much alive.

The story of Lal Bihari “Mritak” is one of the strangest legal battles in Indian history. It is tragic, absurd, and deeply revealing of how fragile identity becomes when systems are corrupt. It proves that in some places, being alive is not enough. You need paperwork to prove it.

The “Death” of Lal Bihari (1975)

In 1975, Lal Bihari was a 20-year-old handloom weaver living in Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh. Like many young men, he approached a bank for a small loan. The bank officer looked at the records and calmly informed him that he was not eligible.

The reason was simple.

According to government records, Lal Bihari was dead.

Without his knowledge, his uncle had bribed a local land official, the lekhpal, with around three hundred rupees to register Lal Bihari as deceased. Once the records were changed, the uncle legally inherited Lal Bihari’s ancestral land of roughly one acre.

In one stroke of a pen, Lal Bihari lost his land, his legal identity, and his existence in the eyes of the state.

The 19-Year Life of a “Ghost.”

Lal Bihari soon realised something terrifying. Courts moved slowly, officials avoided responsibility, and no one seemed interested in correcting a mistake that benefited the powerful.

So he changed strategy.

If the system refused to acknowledge his life, he would force it to confront him.

His methods were bizarre, desperate, and darkly logical.

He tried to get arrested by kidnapping his own cousin, the son of the uncle who stole his land. His logic was simple: if the police arrested him, they would have to file charges against a living man. The police refused, saying they could not arrest someone who was officially dead.

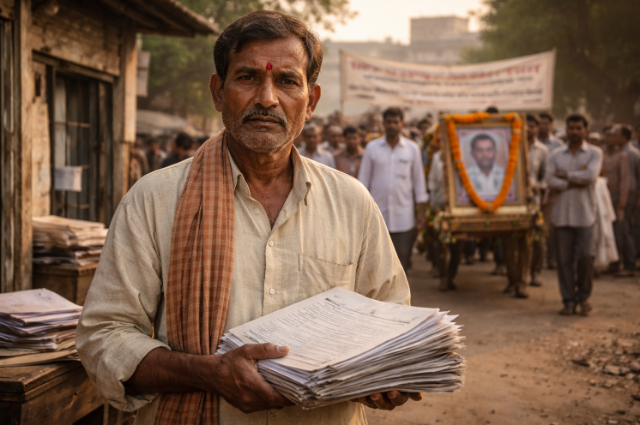

He organised mock funeral processions for himself, marching through Azamgarh and shouting that the government should bury him properly if he was truly dead.

He asked his wife to apply for a widow's pension. When officials rejected the application because Lal Bihari was standing in front of them, he demanded a written explanation stating that he was alive.

Each rejection became evidence.

Each humiliation became documentation.

The Political Stunt

When courts and officials still delayed, Lal Bihari escalated further.

He contested elections.

Not because he expected to win, but because filing nomination papers forced the Election Commission to verify his existence. He stood against powerful figures like Rajiv Gandhi in 1989 and V.P. Singh, using elections as a legal loophole to demand recognition as a living citizen.

The system could ignore a weaver. It could not easily ignore an election candidate.

The Name That Changed Everything

Out of frustration and defiance, Lal Bihari officially added the word “Mritak,” meaning “deceased,” to his name.

From then on, he signed every letter as “Late Lal Bihari Mritak.”

It was satire turned into survival. By calling himself dead, he exposed the absurdity of a system that insisted he was not alive.

Victory After 19 Years

After nineteen years, six months, and twenty-three days, the fight finally ended.

On June 30, 1994, a District Magistrate reviewed his case and officially declared Lal Bihari alive in government records.

The twist was unexpected.

Instead of immediately reclaiming his land or seeking revenge, Lal Bihari forgave his uncle. He said the struggle had given him a larger purpose than property.

He had seen how many others were trapped like him.

The Mritak Sangh: The Association of Dead People

Lal Bihari founded the Mritak Sangh, an organisation for people who were declared dead on paper due to land disputes, inheritance fraud, or corruption.

Today, the group reportedly has more than twenty thousand members across India.

In 2003, Lal Bihari won the Ig Nobel Peace Prize for what the organisers called “prolific post-mortem activism.” Ironically, since he was officially “dead” for years, he was denied a visa to travel to the United States to receive the award.

The 2026 Connection: Digital Identity and New Threats

In today’s India, paper deaths are harder to pull off due to Aadhaar, digitised land records, and the Digital Personal Data Protection framework. But the core issue has not disappeared. It has evolved.

Identity theft, data manipulation, and digital exclusion are the new versions of the same crime.

In recent years, Lal Bihari, now in his seventies, made headlines again by demanding a licence for an AK-47. His argument was darkly symbolic. Living people have revolvers, he said. Dead people need stronger protection from the land mafia.

It sounded absurd. But then again, so did being declared dead while breathing.

Lal Bihari’s story is not folklore. It is a warning.

It shows how identity is not just who you are, but what the system agrees you are. When records lie, truth becomes irrelevant. When bureaucracy fails, survival requires creativity.

He was alive all along.

The system just needed nineteen years to catch up.

. . .

References:

- Lal Bihari Mritak – Wikipedia

- Ig Nobel Prize Winners 2003 – Official Ig Nobel Website

- The Hindu – Articles on Lal Bihari and Mritak Sangh