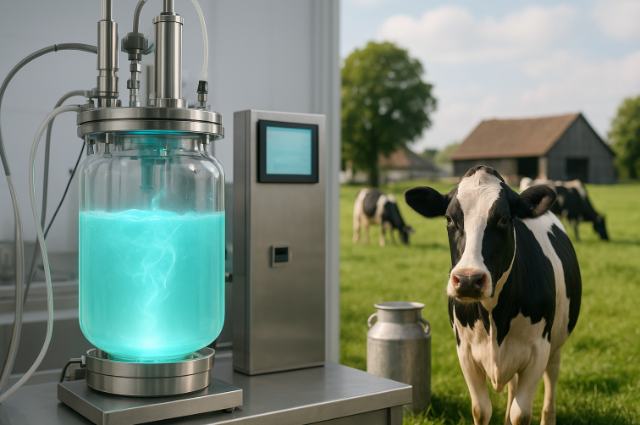

Precision fermentation (PF), the process of programming the microorganisms to produce specific proteins, fats, enzymes, or other functional ingredients is quickly moving from biotech labs into mainstream food production. Its rise is not solely just an innovation story; it represents a structural challenge to the traditional culinary supply chain, from farm production to distribution, and even culinary identity.

We have been fermenting food for ages. Yes, our ancestors figured out that microorganisms like yeast have the capability that transform and preserve food. Often, the fermented ingredients create rich flavors and can bring about nutritional benefits, also enhancing and improving our gut health. Commonly fermented foods in daily life are yoghurt and cheese (fermented milk), kimchi and sauerkraut (fermented cabbage), miso (fermented soy beans), sourdough bread (fermented dough), and wine (fermented grapes). As the name indicates, Precision Fermentation is much more targeted. It focuses on preparing specific ingredients in a highly controlled way.

The Disruption at the Ingredient Level:

Traditional culinary supply chains will depend on these agricultural inputs: dairy products from cows, rennet from calves, egg whites from poultry, and gelatin from animal collagen. PF decouples many of these ingredients from livestock completely. Microbial production of casein, whey, ovalbumen, or heme means there is a stable output independent of climate, disease, and land availability. There is also steady quality and operational performance (e.g., stretch of cheese, foaming of egg whites). Also, reduced price variability once economies of scale are reached. This will directly threaten the farmers who historically used to supply these raw materials.

Pressure on Farming Economies:

Farmers raising livestock and specialty crops encounter two major pressures:

- Demand displacement: If dairy proteins, which are PF-derived, achieve price equality, processors may turn away from traditional milk inputs.

- Margin compression: Even partial ingredient substitution could minimise farm-gate prices.

Rural communities dependent on animal agriculture may experience some economic shock unless transitions or other revenue streams are developed.

Impact on Food Manufacturers and Distributors:

Food manufacturers may actually embrace PF ingredients because they provide: predictable supply chains, enhanced food safety profiles (no pathogens, fewer allergens depending on the protein), customizable performance (e.g., designer fats for specific melt points).

However, distributors tied to cold-chain logistics, fresh dairy, or meat products may need to restore if ingredient volumes transfer toward shelf-stable fermented components.

Chefs and Culinary Traditions:

Culinary culture depends heavily on terroir, animal husbandry, and more regional specialties. Precision fermentation challenges this by standardizing flavors and textures, so we can possibly decrease the regional variations. Also, by dissociating iconic dishes from their agricultural origins, for example, cheese without cows or ice cream without dairy. And also creating new ingredient categories, possibly modifying classic recipes and techniques. Some chefs view PF as a creative tool; others see it as a possible risk to authenticity.

Regulatory and Ethical Landscape

Regulators must balance invention with safety and labeling transparency. Key debates for this include: Should PF proteins be indicated as “animal-free,” “fermented,” or something else? How should intellectual property around engineered microorganisms be supervised/managed? What ethical considerations arise when PF outperforms/surpasses small-scale farmers? Consumer trust will depend on clear communication around these issues.

Future Scenarios

- Optimistic Scenario: PF integrates with traditional agriculture, providing new income programs (feedstock crops, hybrid products, specialty fermented proteins) while elevating sustainability.

- Displacement Scenario: PF reaches cost superiority for several key ingredients, decreasing the demand for animal-based commodities and restructuring supply chains around fermentation hubs instead of farms.

- Coexistence Scenario: PF dominates in processed-food ingredients, while traditional agriculture stays strong in whole foods and premium products.

Case Study:

Focus on the regulatory debate involving a major food tech company introducing a precision-fermented protein substitute that undercuts traditional farmers, highlighting the tension between sustainability and cultural food practices.

Here we are providing a focused narrative-style explanation of that regulatory debate:

A major food and technology company has launched a precision-fermented protein that can substitute a popularly used animal-derived ingredient at a fraction of the environmental cost. Backed by lifecycle analyses and data showing sharply lower land use, water consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions, the company discloses the product as an important tool for meeting national climate targets and acquiring a resilient food supply. But its rapid ascent has initiated a regulatory and cultural dispute.

The Regulatory Tension

Regulators face pressure from two sides.

The innovation and sustainability camp:

Environmental ministries, climate-policy advisors, and urban consumers debate about precision fermentation as a scalable, low-impact alternative. They argue that: national emissions goals will be impossible to reach without moving away from methane- and land-intensive livestock. New protein sources extend supply chains, reducing vulnerability to droughts and global shocks. International competitors are already favouring such products, meaning slow regulation could result in domestic economic disadvantage for the country. These groups drive for streamlined approval, government procurement, and even subsidies to fast-track adoption.

The agricultural and cultural heritage camp:

Traditional farmers— producing the animal-derived ingredient being replaced—argue that the new protein cuts away their livelihoods with a product that can be manufactured in fermentation tanks anywhere. Their concerns include: loss of rural economic stability and multigenerational farm income. The erosion of cultural food traditions tied to livestock agriculture. Also, fears of corporate concentration: a shift from many farmers to a few biotech companies controlling the protein supply. They support slower regulatory approval, origin-label protections, and transition assistance—if not outright barriers to protect domestic agriculture.

The Political Fault Line:

The regulatory debate reveals the separation between climate-driven policy, which focuses on performance and carbon reduction, and cultural food personality, which values heritage, taste, rituals, and the social role of farming. Politicians, especially from rural areas, warn that supporting lab-grown or fermented substitutes too quickly risks “cultural alienation,” while urban policymakers counter that climate timelines can’t wait for cultural adaptation at a generational pace.

The Emerging Compromise:

Some regulators are discussing: differentiated labeling (“fermentation-derived” vs. “farm-derived”), transition funds for farmers to move to specialty or regenerative markets, caps or phased rollouts to manage the economic impact, compulsory transparency on corporate licensing, and strain ownership.

But each of these proposed compromises has some critics, and the debate remains a flashpoint in national food-system policy.

Precision fermentation is not basically a food-tech innovation; it is a supply-chain revolution. Its growth could move out of place traditional agricultural systems, change culinary practices, and reshape global food economics. Whether PF becomes a threat or a complementary force will rely upon policy choices, adoption strategies, investment flows, and the capacity of both farmers and culinary professionals to adapt.

. . .

References: