What Digital Speed Is Quietly Doing to the Human Mind

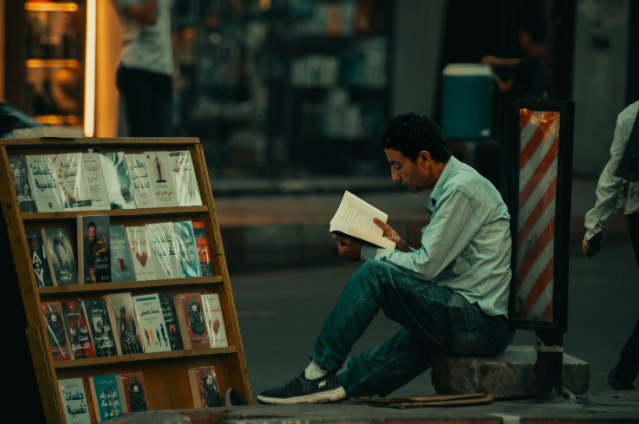

There was a time when reading demanded surrender. A book did not tolerate impatience; it required the reader to slow down, to submit to its pace, to remain still long enough for thought to unfold. Today, that kind of reading feels increasingly unfamiliar. Pages stretch too long. Paragraphs ask too much. The mind, restless and alert for interruption, resists immersion.

This is not a failure of intelligence. It is a transformation of habit.

Over the last decade, many of us have acquired an uneasy sense that our thinking has changed. Concentration fractures more easily. We skim where we once lingered. We gather information efficiently, yet struggle to remain with an idea long enough to exhaust its meaning. The internet has not made us ignorant; it has made us impatient. And impatience, when habitual, reshapes the mind.

The question is no longer whether the internet influences how we think. The question is whether it is training us to think in a fundamentally different way — and what we may be losing in the process.

The Subtle Shift from Depth to Velocity

The internet excels at one thing above all others: speed. It delivers information instantly, compresses distance, and collapses waiting time. This efficiency is often celebrated as intellectual progress. Yet speed is not neutral. When repeated daily, it becomes an expectation; when expected, it becomes a dependency.

Online reading rarely proceeds in a straight line. Hyperlinks invite detours. Notifications demand attention. Tabs multiply. Each interruption feels minor, even harmless, but together they produce a pattern of fractured engagement. The mind learns to anticipate distraction. Instead of sinking into an argument, it hovers above it, prepared to move on at the first sign of resistance.

This mode of engagement favors breadth over depth. It rewards recognition rather than reflection. Ideas are encountered briefly, often stripped of context, before being replaced by the next item in an endless stream. The result is not the absence of knowledge, but the thinning of understanding.

Reading Is Not Just Reading

Reading is often treated as a basic skill, but cognitively, it is a complex act. Deep reading — the kind required for philosophy, literature, and serious analysis — activates memory, imagination, empathy, and critical judgment simultaneously. It depends on continuity and silence. It requires the mind to remain with uncertainty long enough for meaning to form.

Digital environments rarely allow such continuity. They encourage rapid evaluation rather than sustained interpretation. Text becomes something to be processed, not inhabited. Over time, this changes how the brain allocates attention. Neural pathways adapt to speed, novelty, and fragmentation.

The mind becomes highly efficient at locating information, yet less practiced at integrating it. We become excellent navigators, but weaker thinkers.

When Tools Shape Thought

Human beings have always been shaped by their tools. The invention of the clock altered how people understood time. The printing press reshaped memory, authority, and learning. Each technological shift brought both gains and losses.

What makes the internet distinctive is its totality. It does not replace a single activity; it absorbs many. It is simultaneously a library, a newspaper, a marketplace, a classroom, and a social space. As a result, it exerts a continuous influence on attention.

The logic of digital systems favors optimization. Algorithms are designed to minimize friction, reduce effort, and maximize engagement. Ambiguity, slowness, and difficulty are treated as inefficiencies. Yet these very qualities are essential to serious thought. When the dominant intellectual environment discourages difficulty, the mind adapts accordingly.

The Industrialization of Mental Life

Modern digital platforms operate according to principles borrowed from industrial efficiency. Tasks are broken into smaller units. Information is streamlined. Output is measured. Productivity is quantified. These principles, applied to physical labor, transformed factories. Applied to mental life, they transform thinking itself.

The danger is not that machines think for us, but that we begin to think like machines. When cognition is reduced to rapid processing, depth appears wasteful. Reflection seems slow. Contemplation feels unproductive.

In such an environment, intelligence risks being redefined. To know becomes to access. To understand is to retrieve. Judgment is replaced by search results. The mind becomes an interface.

Education Under Pressure

These shifts are increasingly visible in education. Students read more than ever, yet often struggle with long-form texts. Essays reveal familiarity with concepts but difficulty sustaining arguments. Learning becomes transactional: information is acquired for immediate use, then discarded.

Institutions often respond by adapting to shortened attention spans rather than challenging them. Content is simplified. Reading loads shrink. Complexity is reduced. While such adjustments may appear compassionate, they risk normalizing cognitive fragility.

Education, at its best, strengthens the mind’s capacity to endure difficulty. When difficulty is removed, growth stalls.

Are We Just Being Alarmist?

Every new technology provokes anxiety. Critics once warned that writing would weaken memory, that printed books would encourage laziness, that television would destroy attention. Some of these fears were exaggerated; others were justified.

The point is not to romanticize the past or demonize the present. The internet has expanded access to knowledge, enabled collaboration, and amplified voices long excluded from public discourse. These gains are real and significant. But acknowledging benefits does not require denying costs. Progress that ignores its own consequences is not wisdom.

What Is at Risk

The greatest risk is not distraction, but shallowness. A culture trained to skim struggles to reflect. A public accustomed to fragments finds sustained argument exhausting. Democracy, scholarship, and ethical reasoning all depend on citizens capable of slow thought. Deep reading is not merely a preference; it is a form of intellectual resistance. It preserves the mind’s ability to dwell, to question, and to imagine alternatives. Without it, thought becomes reactive rather than reflective.

Choosing Slowness in a Fast World

The internet will not slow down. That choice belongs to us. Preserving depth requires intention. It means carving out spaces free from interruption. It means reading without hyperlinks, thinking without notifications, and accepting that understanding takes time. This is not nostalgia. It is self-defense. If intelligence is to remain more than efficient data handling, the mind must retain its capacity for patience. In a world optimized for speed, slowness becomes a moral and intellectual act.

The question is not whether the internet is making us “stupid.” That framing is too crude. The real question is subtler and more urgent: what kind of minds are we becoming? If we allow speed to replace depth, convenience to replace judgment, and access to replace understanding, we may find ourselves informed yet shallow, connected yet unreflective. The future of thinking depends not on faster machines, but on whether human attention can still afford to linger.