January 1984.

A charred Ambassador car bearing licence plate number KLQ 7831, found in a field with a badly burnt and unrecognizable body of a man inside.

This was how it started.

What was initially thought of as an accident resulting in a fire that killed the person behind the steering wheel of the burnt car later gave way to one of the longest manhunts in the State of Kerala.

The charred corpse, predictably, was assumed to be that of the owner of the car - Sukumara Kurup, an expatriate from Cheriyanadu who. Besides, at that moment, there was no reason to imagine anything sinister other than an accident or perhaps even a desperate suicide. A sudden death in a fire masked by the charcoal night seemed tragic, but plausible. But that was no reason to push aside the crime scene that looked crafted. When the police first reached the scene, they were met with scorch marks, the smell of petrol, a pair of discarded gloves, and a blood-stained petrol can - all signs inconsistent with an accidental fire. The car was traced back to Kurup, but the burnt body inside resisted identification. Nothing - no rings, no watch, not even a pair of slippers survived the fire. Only a pair of half-burnt undergarments worn by the victim remained.

The forensic examination that followed was anything but routine. What should have been a simple confirmation of a man’s death in a fire instead unfolded like a puzzle that refused to behave. Under the expert hands of Dr. B Uthaman, the forensic surgeon, it was found that there was no soot in the lungs of the man who was supposedly killed in a fire. Nor where there any telltale black dust that every victim of a fire inhales in their final, desperate breaths. Above it all, the burns on the body were all laid in an oddly theatrical manner, as though it was arranged for effects rather than inflicted by the chaos that must have ensued in a normal fire accident. Additionally, toxicological signs on the abdomen suggested fatal poisoning. Dr. Umadathan had from body dimensions and skeletal remains deduced that the victim was between 30-35 years of age and about 6 feet tall, roughly matching Kurup’s profile.

To the untrained eye, that was a tragedy.

But to the expert surgeon, that was performance, written by someone with an alarming degree of confidence.

This wasn’t just an accident anymore.

The victim had died before the fire was set.

Once this conclusion was reached, the investigators now had to identify the victim.

If it was not Sukumara Kurup, then who was the man inside the car?

The process of identification of the corpse was methodical and grounded in careful detective work. The police began by examining recent missing persons reports in and around Alappuzha and Ernakulam Districts. A few leads emerged. However, one in particular stood out. That was a complaint from the family of a Filim Representative named Chacko hailing from Alappuzha who had not returned home on the eventful night of January 21, 1984 - the very night the death/murder had occurred.

The police went ahead with the possibility of Chacko being the victim. Witness statements only aided the conclusion they were slowly reaching. Locals from a place called Karuvatta recalled seeing Chacko shortly before he disappeared. Many even saw him in the company of three men on that night, who were later identified as Bhaskaran Pillai - Sukumara Kurup’s brother-in-law, Ponnappan - Kurup’s driver and a man named Shahu

Following this, in a landmark endeavor for forensic science and crime investigation in Kerala, investigators exhumed the buried body, which was originally handed over to Kurup’s relatives. The experts relied on a technique known as photographic superimposition, which was used for the first time in Kerala. The skull from the crime scene was photographed and then compared layer by layer to a portrait of Chacko. Surprisingly, or maybe not, everything matched perfectly - jawline, eye sockets, nasal bridge, and even dental structure.

That, however, wasn’t the last of the proofs. A further painstaking process followed. The forensic experts reconstructed the right foot of the corpse, wiring together the bones and recreating the flesh in clay, based on the anatomical averages drawn by studying various dead bodies. Chacko’s footwear fitted perfectly. Even the indentations of the toes.

Thus, in a triumph of science and through police work, the charres corpse once persumed to be Kurup was now identified as that of K.J Chacko. The ‘accident’ became a murder.

Now the question was, where was Sukumara Kurup whom everyone believed to have died that night?

As soon as the forensic team declared that the corpse did not belong to Kurup, several facts aligned sharply. The prolonged absence of Kurup no longer looked like the disappearance of a dead man - it resembled the behaviour of a fugitive who had orchestrated a disappearance. The missing-person complaint filed by Chacko’s family which was initially treated as routine, now offered a clear link. The fact that witnesses testified seeing Chacko entering a car with three other men only added to the already piled-up evidence that hinted at murder.

The breakthrough came when the investigators questioned Bhaskaran Pilla, Kurup’s brother-in-law, who had burn marks on his face and hands, and even hair, regarding the whole thing and in panic said he had murdered Kurup. He said that Kurup had promised him money and a job abroad, and when that promise failed, resentment turned into betrayal, claiming the victim was killed in anger over betrayal.

But that confession alone still left doubts because another story had surfaced from the driver, Ponnappan. When the police brought him in, he told a different tale, that he had accidentally hit a man with the car, panicked, and in a bid to conceal the accident, burned the body along with the vehicle.

This conflicting pair of confessions made investigators sceptical. A hit-and-run followed by a hasty cremation in a car did not square with the forensic evidence. Post-mortem reports had already shown that the victim died before the fire, and that too because of poisoning, indicating deliberate killing and staging.

Under renewed and sustained interrogation, both Pillai and Ponnappan, along with the third accomplice, Chinnakkal Shahu, who had initially assisted and then later agreed to cooperate, began to yield. Pillai admitted that he, Ponnappan, and Shahu had followed instructions from Kurup. They had chosen a random man who resembled Kurup, coerced him into the car, drugged him, strangled him, disfigured his face, dressed him in Kurup’s clothes, and set him ablaze in the Ambassador to simulate Kurup’s death.

Shahu, once caught, turned approver, that is, he agreed to testify for the prosecution in exchange for immunity or reduced charges. His testimony corroborated Pillai’s admissions. Together, their accounts provided a detailed reconstruction of the crime, including the night of abduction, the method of killing (ether-laced liquor, strangulation with a towel), the disfigurement and burning, and the staging of an “accident.”

And so it was found that the man they thought had perished in an accidental fire was the one who set the car on fire, mercilessly killing someone else.

What led to the conspiracy that resulted in Chacko’s death?

One word. Greed.

Sukumara Kurup had taken a life insurance policy for an amount of Rs. 8 Lakhs, which in the 1980s was a substantial sum. His plan was to fake his own death so that his nominees could claim that money. Police records of the confessions of the three other convicts show that he initially attempted to find a dead body look-alike from a mortuary or a cemetery. When that seemed impossible, he had to resort to a more sinister plan - kill a living man who resembled him physically.

According to the investigators, Kurup was conducting a bungalow in his hometown. For someone who lived a lavish life, Kurup did not have too much savings to put into this. Besides this, some reports suggest that downturns in Gulf economies and potential financial instability may have pressured him into taking such a drastic step. The insurance money, if realised, would have eased financial burdens and financed his aspirations for a comfortable, affluent homecoming.

This reveals a chilling truth that greed can make a man go to any extent.

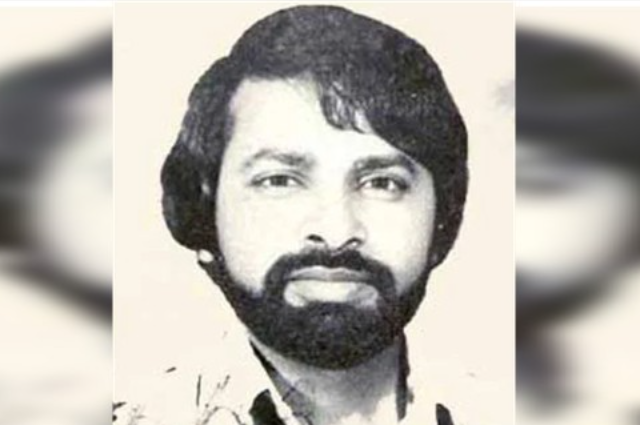

Sukumara Kurup: The man who disappeared

While the three other accomplices of Kurup were arrested, Kurup was nowhere to be found. He had absconded. Now, absconding isn’t merely an act of disappearance. It is a test of the system’s resolve and seriousness. When a person accused vanishes, what remains behind is not just an absence, but a bunch of unanswered questions about accountability, enforcement and institutional resolve.

Following his disappearance, the authorities scrambled to locate him, media attention intensified, and public outrage surged, highlighting how such incidents capture collective attention only when amplified by urgency. Yet, the aftermath also revealed systemic weaknesses such as delays in action, lack of clear communication, and the ease with which accountability can slip away. The police had in multiple occasions received various calls from civilians who claimed to have seen the fugitive. However, following those traces led them nowhere.

Decades have passed since the crime, and Sukumara Kurup’s case has effectively become a cold case, highlighting the limitations and challenges of law enforcement in tracking and apprehending fugitives over time. The mystery of his disappearance has captured public imagination, inspiring numerous documentaries, news features, and even a feature film. While some portrayals risk glorifying Kurup, presenting him as a daring figure to younger audiences, others focus on the human cost of his actions, the devastating aftermath for Chacko’s family. His wife, pregnant at the time of the murder, had to raise a child without a father, while his son grew up never knowing him.

Greed, while a common human trait, can take many forms. Yet the kind of greed that drives a person to take an innocent life, stage a gruesome murder, and manipulate justice for personal gain is beyond just an ordinary human desire. To idolize such actions is not only morally wrong but profoundly disturbing. Kurup’s crime remains a chilling reminder of how ambition and avarice, when unchecked, can destroy lives and leave a lasting scar on society.

. . .

REFERENCES:

- Shaji, K. (2024, January 21). Chacko murder case: 40 years on, Kerala’s longest-wanted fugitive still elusive. South First.

- Varma, V. (2021, January 10). Finding Sukumara Kurup: Recreating a 37-year-old murder case that has become folklore in Kerala. The Indian Express.

- Balakrishnan, A. (2021, January 26). Wanted Since 1984: The Incredible Tale of India’s Longest Fugitive.. Medium.

- Rajendran, S. (2017, June 19). 30 Years & Still on the Run: The Mystery of Kerala’s Most Wanted. The Quint.