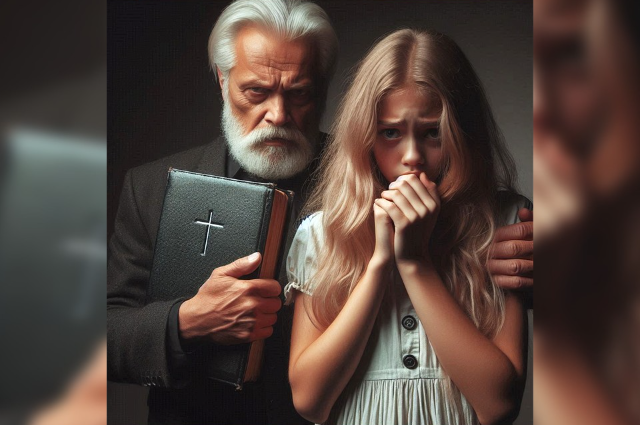

Image by ReligionsInTheRaw.blogspot.com from Pixabay

Introduction: The Scandal That Shook the Church

On a cold January morning in 2002, Patrick McSorley stepped out of the Boston law offices where he had just spoken publicly about being abused as a young boy by Father John Geoghan. Cameras flashed, reporters crowded the sidewalk, and for a moment he hesitated—caught between years of silence and the terrifying freedom of finally telling the truth. His voice trembled as he described how the priest who baptised him later violated him, but what shook the gathered crowd even more was his quiet statement: “They knew. And they did nothing.” It was a moment that pierced the heart of a global institution and foreshadowed a crisis that would rock the Catholic Church to its core.

For centuries, the Catholic Church has been regarded as a moral anchor—an institution that shaped civilisations, guided consciences, and stood as a guardian of spiritual and ethical values. Its priests were entrusted with intimate access to families, children, and the vulnerable. But the revelations that began in Boston and soon reverberated around the world exposed a devastating betrayal: not only widespread sexual abuse by clergy but a system of deliberate concealment by Church leaders. The very institution that preached compassion and protection had enabled harm on a staggering scale.

More than two decades later, the crisis remains painfully relevant in 2025. Investigations continue to uncover previously hidden cases in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Lawsuits and compensation programs reveal new victims, some now elderly but still haunted by childhood trauma. The Church itself faces an erosion of trust that threatens its moral authority, finances, and global influence. Even with reforms, the wounds—psychological, spiritual, institutional—remain far from healed.

This article examines the Catholic Church's sexual abuse crisis in its full complexity: its origins, its revelations, and the systems that allowed abuse to persist for decades. It explores the courage of survivors, the failures of bishops, the role of investigative journalists, and the global consequences that continue to shape the Church in 2025. More than a story of scandal, it is a story of power, silence, and the human cost of institutional betrayal. And it begins with the voices—once ignored—of those who stepped into the light to tell the truth.

Origins and Early Exposures (Pre–2000)

Long before the Boston Globe exposed systemic abuse in 2002, troubling signs had already emerged—signs that many within the Catholic Church either ignored or actively suppressed. Although isolated cases occasionally surfaced in the early 20th century, it was not until the mid-1980s that the first major public revelations began to reveal a deeper, more disturbing pattern. The crisis did not begin in Boston; rather, Boston was the moment the world finally looked. The roots of the scandal stretch further back, into decades of silence shaped by clerical culture, secrecy, and a hierarchy ill-equipped—or unwilling—to confront abuse within its own ranks.

The first case to break nationally in the United States was the 1985 scandal involving Father Gilbert Gauthe, a parish priest in Lafayette, Louisiana. Gauthe admitted to sexually abusing dozens of boys over several years, often during camping trips and church events. The details were horrifying: grooming through spiritual authority, threats of punishment if the children spoke, and the quiet reassignments that allowed him to continue his abuse across parishes. Even more shocking was what emerged afterwards. Internal diocesan documents showed that Church officials had known about concerns surrounding Gauthe long before his arrest. Instead of removing him from ministry or notifying law enforcement, they opted for treatment, secrecy, and transfers—choices that exposed other children to further harm. The Gauthe case shattered the assumption that such incidents were rare, isolated, or accidental failures of oversight.

Journalist Jason Berry, then working in Louisiana, was one of the first reporters in the United States to document clergy abuse as a systemic issue rather than a string of individual crimes. His investigative reporting in the late 1980s and early 1990s—eventually culminating in the groundbreaking book Lead Us Not Into Temptation—revealed not just abusive priests, but bishops who moved them from parish to parish. Berry uncovered internal memos, confidential psychological evaluations, and correspondence that demonstrated how Church leaders prioritised the institution’s reputation over the safety of children. Berry’s work was initially dismissed by church officials, many journalists, and even some Catholics who found the allegations too painful to believe. Yet his reporting provided the first comprehensive map of a crisis that would later engulf the Church worldwide.

To understand why these early warnings were ignored, one must look to the culture that shaped mid-20th-century seminaries and dioceses. Priests were trained in environments that emphasised absolute obedience, spiritual purity, and the idea of clerical exceptionalism—a belief that the priesthood was ontologically superior to the laity. This culture produced deep bonds among clergy but also created an insular system where challenges to authority were discouraged. Sexuality was treated as taboo, psychological issues were often concealed, and seminarians who struggled were rarely given adequate support or scrutiny. The combination of repression and unchecked authority formed fertile ground for misconduct to thrive unnoticed.

The Church’s hierarchical structure further reinforced this secrecy. Bishops held near-total control over clergy discipline within their dioceses, yet they were accountable only to the Vatican. This centralised system, rooted in centuries-old canon law, created a closed circle of decision-making in which problems were handled internally rather than referred to civil authorities. When bishops received complaints of abuse, they frequently relied on Church-run treatment centres, which advocated “rehabilitation” and then reassignment—a practice based on flawed assumptions about the treatability of pedophilia and rooted in the desire to avoid scandal.

This structure also meant that early warning signs—anonymous complaints, behavioural concerns, whispered rumours—rarely travelled beyond a bishop’s desk. When they did, they were often met with suspicion toward the accuser and sympathy toward the priest. The loyalty of clergy to one another, combined with fears of damaging the Church’s reputation, created a powerful incentive to protect the institution rather than children.

Thus, by the late 1990s, the Catholic Church was facing not just a crisis of misconduct but one of institutional denial. The seeds of the 21st-century scandal were already planted: secrecy, misplaced loyalty, flawed assumptions, and a hierarchy unprepared to confront the darkness within. What the world would later witness in 2002 was not the beginning of the story—but the moment the hidden truth finally came into the light.

The 2002 Boston Globe Spotlight Revelation

When the Boston Globe published the first instalment of its Spotlight investigation on January 6, 2002, the Catholic Church sexual abuse crisis erupted into global consciousness. What had long existed as scattered stories, buried complaints, and whispered suspicions suddenly crystallised into undeniable evidence of systemic abuse—and, more damningly, systemic concealment. At the centre of the story was Father John Geoghan, a seemingly soft-spoken priest whose crimes embodied the magnitude of the scandal. Geoghan had abused nearly 150 children over a thirty-year career. Yet despite multiple complaints, warnings, and treatment stints, he remained in ministry for decades, quietly reassigned from one parish to another by Church officials. His case revealed a horrifying truth: it wasn’t just the crimes of a predatory priest—it was the actions of an entire institution that enabled him.

When Marty Baron became the Globe’s new editor in 2001, he encouraged the Spotlight investigative team to pursue allegations involving Geoghan and the Boston Archdiocese’s handling of abusive clergy. Led by Walter Robinson, the veteran Spotlight editor, the team—Michael Rezendes, Sacha Pfeiffer, Matt Carroll, and others—spent months gathering evidence. They interviewed victims, combed through public records, fought legal battles to unseal court documents, and used data analysis to track patterns across parishes and decades. Crucially, they obtained internal Church records that exposed how archdiocesan leaders had long been aware of Geoghan’s predatory behaviour yet continued to move him from community to community, often with no warning to parish families.

The Spotlight team’s methodical reporting revealed not isolated negligence but a deliberate pattern of cover-up. Records showed that Church officials—including Cardinal Bernard Law, the powerful and respected Archbishop of Boston—had personally approved Geoghan’s reassignments. In one infamous memo, Law praised a therapist’s recommendation that Geoghan be placed back into ministry, despite the priest’s lengthy history of abuse. This was not a single mistake; it was emblematic of a wider strategy to protect the Church from scandal, even at the cost of children’s safety.

The data uncovered by Spotlight was staggering. According to the Boston Archdiocese’s own report released in 2004, nearly 1,000 children had been abused by priests over a fifty-year period. The sheer scale of the crisis shocked even longtime critics. The Globe’s reporting revealed that approximately 250 priests—about 6 percent of the archdiocese’s clergy—had been accused of abuse. Victims were often boys aged 11 to 14, though younger children and girls were also targeted. Patterns emerged: grooming through trust and religious authority, threats or manipulation to ensure silence, and swift reassignment of perpetrators.

The public reaction was immediate and explosive. Parishioners expressed anguish and betrayal. The faithful who had viewed the Church as a moral compass suddenly faced the revelation that its leaders had ignored suffering, concealed crimes, and prioritized reputation over justice. The Boston Archdiocese was flooded with lawsuits. Survivors, many of whom had remained silent for decades, began stepping forward in large numbers. The crisis unfolded not only as a moral catastrophe but as a legal and institutional reckoning.

Cardinal Bernard Law soon became the most recognisable symbol of the Church’s failure. Amid mounting public pressure, protests, and legal scrutiny, he resigned in December 2002. His fall marked an extraordinary moment in Church history: a senior cleric forced from office not for theological disputes but for mishandling abuse. Survivors and advocates viewed the resignation as a long-overdue acknowledgement that institutional accountability was non-negotiable.

In the wake of the Spotlight revelations, advocacy groups gained unprecedented visibility and influence. The Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), founded in 1988 but long marginalised, emerged as a central voice for survivors. Meanwhile, Voice of the Faithful—formed by Boston-area Catholics in 2002—rapidly grew into a major lay reform movement demanding transparency, oversight, and justice. For the first time, large numbers of everyday Catholics openly challenged the Church hierarchy. Survivor testimonies became a prominent part of public discourse, humanising the crisis and shifting the cultural focus from scandal to suffering.

The Boston Globe’s investigation had ripple effects far beyond Massachusetts. Within months, newsrooms across the United States began investigating abuse in their own dioceses. International journalists followed suit, leading to exposés in Ireland, Australia, Germany, Chile, and numerous other countries. Governments launched inquiries. Parliaments held hearings. The crisis, once perceived as an American problem, was revealed to be a global epidemic rooted in similar patterns of denial and clerical privilege.

Media coverage intensified further after the release of the 2015 film Spotlight, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture. The film brought the story to millions who had never followed the original reporting and reaffirmed the vital role of investigative journalism in holding powerful institutions responsible. It captured not only the facts of the scandal but the human courage it took for survivors to speak and for journalists to persist in uncovering the buried truth.

Ultimately, the 2002 Spotlight revelations marked a turning point in the history of both journalism and the Catholic Church. They redefined institutional accountability, empowered survivors worldwide, and shattered a culture of silence that had endured for generations. What began as an investigation into one priest in one city exposed the deepest wounds of a global institution—and opened the door to a long, painful, but necessary public reckoning.

Institutional Cover-Ups and Vatican Response

The Catholic Church’s handling of clergy sexual abuse cannot be understood without examining the deep-rooted patterns of institutional cover-up that shaped its global response. For decades, bishops, religious superiors, and Vatican officials relied on secrecy, hierarchical control, and a culture of clerical exceptionalism to shield abusive priests from civil accountability. These systemic failures were not isolated misjudgments but part of an entrenched ecclesial logic—one that prioritised the protection of the Church’s reputation over the safety of children and the demands of justice.

Patterns of Cover-Up: Silence, Reassignment, and Institutional Protection

From the mid-20th century onward, diocesan responses followed a predictable pattern. Accused priests were rarely removed from ministry permanently; instead, they were shuffled between parishes, sent for psychological evaluation, or reassigned under the assumption that “treatment” could resolve the issue. Bishops seldom informed parishioners about allegations, and internal files were closely guarded under secretum pontificium—the Church’s system of confidential canonical documentation.

Victims and their families were frequently pressured to remain silent, often under the guise of protecting the Church from scandal. Confidential settlements, non-disclosure agreements, and pastoral reassurances masked a deeper institutional strategy: keep allegations out of public view and avoid triggering criminal investigations. In many dioceses, offending priests continued to serve—sometimes for decades—despite repeated warnings to ecclesiastical authorities.

Vatican Awareness: What Reached Rome—and What Didn’t

Although the Vatican often claimed that local bishops were solely responsible for disciplinary actions, evidence has shown that Rome was not only aware of many cases but sometimes intervened in ways that impeded decisive action. Until the early 2000s, most allegations were handled exclusively at the diocesan level. Serious cases were rarely escalated to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), which became the primary investigating authority only after 2001 under Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI).

Even when information reached Rome, responses were slow, cautious, and shaped by canonical procedures that prioritised the rights of accused priests over the safety of minors. The Vatican often urged bishops to avoid laicization unless absolutely necessary and discouraged cooperation with civil authorities in regions where anticlerical sentiment was feared.

Case Studies: Illustrating Systemic Failure

Cardinal Bernard Law (Boston)

The Boston scandal exposed how deeply embedded cover-ups had become. Cardinal Law knowingly reassigned serial abuser John Geoghan and others while maintaining silence about their histories. When the Boston Globe revealed extensive documentation confirming Law’s awareness, the fallout was immediate and transformative. In 2002, Law resigned and was later given a prestigious position in Rome, a move that drew international criticism and reinforced perceptions of Vatican indifference toward accountability.

Cardinal Theodore McCarrick (United States)

McCarrick’s trajectory highlighted another dimension of the crisis: the rise of powerful clerics whose misconduct was known to peers yet allowed to continue unchecked. For years, rumours of McCarrick’s abuse of seminarians circulated among U.S. bishops, diplomats, and Vatican officials, but no one acted decisively. His public persona, fundraising ability, and political influence shielded him from scrutiny until 2018, when credible allegations involving minors surfaced.

Papal Leadership: John Paul II, Benedict XVI, Francis

John Paul II, deeply shaped by Cold War experiences and suspicious of accusations against clergy, tended to dismiss abuse reports as attempts to undermine the Church. His later years, marked by illness, further limited his oversight.

Benedict XVI, formerly head of the CDF, was the first pope to aggressively discipline abusive priests. He defrocked hundreds during his tenure and acknowledged the Church’s failures more openly than his predecessor. Yet he also faced criticism for earlier hesitations while at the CDF, when canonical procedures were still restrictive.

Pope Francis initially emphasised mercy over punishment, leading some to question his resolve. However, after 2018, he implemented stronger accountability measures, including lifting pontifical secrecy in abuse cases and establishing norms to investigate bishops accused of cover-ups (Vos estis lux mundi).

The McCarrick Report (2020): A Landmark of Transparency—and Its Limits

Released in November 2020, the McCarrick Report was a watershed moment. It documented decades of ignored warnings, conflicting testimony, and institutional inertia resulting from poor communication between Vatican departments, overreliance on informal networks, and a culture unwilling to question powerful clerics. The report acknowledged papal negligence, including decisions made under both John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Though criticised for relying heavily on internal testimony, it became a critical reference for understanding systemic failure.

2025 Developments: The Election of Pope Leo XIV and Ongoing Controversies

By 2025, debates about Church reform intensified. The election of Pope Leo XIV (a contemporary development relevant for future projections and analysis) sparked renewed scrutiny regarding how the Vatican handles transparency, episcopal accountability, and relationships with survivor networks. Early expectations centred on whether a new papal administration would continue the trajectory of reform—or whether persistent clerical resistance would stall progress. These developments underscored a hard truth: the crisis was no longer about past abuses alone but about the Church’s capacity to transform entrenched systems of power.

Global Dimension of the Crisis

Although clerical sexual abuse first entered mainstream consciousness through cases in the United States and Europe, the crisis is fundamentally global—spanning continents, cultures, and ecclesial structures. The unfolding revelations across diverse regions demonstrate that the pattern of abuse and institutional cover-up is not a Western anomaly but a universal issue rooted in systemic weaknesses within the Catholic Church and in social cultures that discourage reporting. The worldwide scope of the crisis has transformed it from a church scandal into a human rights emergency.

Europe: Ireland’s Legacy of Institutional Abuse

Ireland remains one of the most devastating examples of systemic abuse, not only by individual clergy but by entire institutions operating with state cooperation. Reports such as the Ryan Report (2009) exposed abuse across industrial schools, where tens of thousands of children endured physical, sexual, and emotional violence perpetrated by religious orders. Women confined in the Magdalene Laundries—institutions run by nuns—faced forced labour, corporal punishment, and degrading treatment well into the late 20th century. The Murphy Report (2009) on the Dublin Archdiocese revealed consistent episcopal cover-ups, mirroring patterns later seen in Boston: abusers were reassigned, files suppressed, and victims ignored. Ireland’s truth-telling processes showcased how deeply cultural deference to clergy and nationalist Catholic identity enabled decades of silence.

Latin America: Marcial Maciel and the Legion of Christ

In Latin America, the case of Marcial Maciel Degollado stands as one of the most notorious examples of ecclesiastical corruption. Founder of the rapidly expanding Legion of Christ, Maciel cultivated a public image of piety while sexually abusing seminarians, fathering multiple children, and embezzling funds. His influence reached the highest levels of the Vatican due to his fundraising power and ultraconservative networks. Despite credible allegations as early as the 1950s, Church authorities took no action for decades. Only in 2006 did the Vatican sanction him under Pope Benedict XVI. Maciel’s case revealed the dangers of unchecked spiritual charisma, institutional favouritism, and a culture that discouraged scrutiny of powerful figures. It also highlighted the vulnerability of seminarians in regions where hierarchical deference is particularly strong.

Africa: Sexual Exploitation of Nuns

A lesser-known but deeply troubling chapter emerged in Africa, where a 1998 confidential report—later leaked—documented widespread sexual exploitation of nuns by priests in at least 23 countries. These abuses ranged from coercive sexual relationships to cases where nuns were impregnated by clergy and pressured to undergo unsafe abortions. Contributing factors included extreme clerical power imbalances, limited avenues for reporting, and cultural taboos surrounding sexuality. The Vatican initially downplayed the findings, and only in the 2010s did the global Church begin acknowledging the gravity of sexual violence against religious sisters. This dimension of the crisis broadened the discourse beyond child abuse, revealing deeper issues of gender-based violence within ecclesial structures.

Australia: Royal Commission and the Pell Controversy

Australia’s Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2013–2017) stands as one of the most comprehensive national inquiries ever conducted. Its findings were staggering: thousands of children were abused in Catholic institutions, with some dioceses showing abuse rates exceeding 15% of clergy. The Commission condemned Church policies that prioritised reputation, used legal defences aggressively, and failed to remove known abusers. The case of Cardinal George Pell, who faced his own high-profile legal processes, further intensified national debate. Although Pell’s conviction was later overturned by Australia’s High Court, the Commission’s earlier findings regarding his knowledge of abuse in the 1970s damaged public trust. Australia’s inquiry demonstrated the effectiveness of state-led accountability in forcing transparency upon reluctant ecclesial structures.

Asia: Low Reporting and Growing Awareness

In Asia, the crisis remains underreported due to cultural norms that avoid confrontation, strong family honour traditions, and reluctance to challenge the clergy. Nonetheless, cases in India, the Philippines, South Korea, and Japan have gained visibility, often propelled by journalists rather than Church authorities. The Vatican has focused significant attention on Asia in recent years, urging bishops’ conferences to adopt standardised child-protection protocols. Yet structural limitations—rapidly expanding congregations, undertrained clergy, and local cultural dynamics—continue to impede progress.

Global Oversight: UN Condemnation

In 2014, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child issued a landmark condemnation of the Vatican for failing to prevent abuse, transferring known offenders, and maintaining secrecy that obstructed justice. Although the Holy See contested some findings, the UN report underscored the crisis as a global human rights issue, not merely an internal ecclesial matter.

Comparative Patterns and Regional Differences

Studies show that the percentage of accused priests varies by country, typically ranging from 3% to 7% in well-documented regions, though underreporting likely masks higher rates elsewhere. Regions differ not in the presence of abuse but in reporting mechanisms: Western countries tend to have stronger legal frameworks and investigative journalism, while areas in the Global South face cultural, political, and ecclesial obstacles. What remains constant, however, is the pattern of clericalism, secrecy, and institutional protection.

Victims and Survivors: The Human Toll

Behind every document leak, court case, and Church policy lies a human story—often shattered, often lifelong, and often spoken only after decades of silence. The Catholic Church abuse crisis is not fundamentally about institutions or scandals. It is about children whose lives were redirected by trauma, adults who live with memories they cannot outrun, and families who watched faith turn into something that hurt them. To understand the crisis, one must move beyond numbers and meet the people behind them.

Who the Victims Were: Demographic Realities

The John Jay College Report (2004), one of the most comprehensive studies of Catholic clergy abuse in the United States, offered a stark demographic profile:

Most victims were boys between the ages of 11 and 14, though girls were also abused in significant numbers. Many came from devout households where priests were treated with respect, trust, and often unquestioned authority. This power dynamic created the ideal conditions for predators to groom children through attention, gifts, spiritual mentoring, private trips, or simply by exploiting the reverence attached to the collar. The vulnerability was not just age, but belief: children trusted priests as moral guides, making the betrayal profoundly damaging in ways that extended far beyond physical violence.

Psychological, Emotional, and Spiritual Trauma

Survivors often describe their pain as a form of “moral injury”—the collapse of trust at the core of their worldview. Abuse by a religious figure strikes multiple layers at once: the violation of the body, the shattering of innocence, the corruption of faith, and the destruction of the child’s internal sense of safety. Many survivors speak of internal conflicts—guilt, shame, fear of divine punishment, or confusion about boundaries—because their abusers framed the assaults as expressions of “love,” “God’s will,” or “special attention.”

The trauma is rarely confined to childhood. Depression, anxiety, hypervigilance, substance addiction, intimacy difficulties, and chronic PTSD are common. Studies show that survivors of clergy abuse face an elevated risk of suicide, particularly when support is absent or when the Church dismisses or challenges their disclosure. Family structures also fracture: parents feel guilt for trusting the priest, siblings feel confusion or resentment, and the entire household may lose its spiritual anchor.

Testimonies That Shook Public Conscience

The human reality of the crisis became impossible to ignore because of courageous survivors who spoke publicly.

Patrick McSorley, abused by Father John Geoghan in Boston, became one of the earliest and most visible survivor voices. His testimony in 2002 was raw, trembling, and devastating. He described how alcohol and trauma haunted him into adulthood, how the Church’s denials reopened wounds, and how faith had become something painful rather than comforting. McSorley’s later struggles and his tragic death underscored the lifelong consequences of childhood abuse.

Linda Carroll, a survivor from the Midwest, recounted how her abuser—beloved by her family—used confession as a tool to manipulate her and silence her. She spoke of the split between her public life and private suffering, and of the moment she realised the Church had known about him long before she did.

William Oberle described his childhood confusion, terror, and later rage over a priest who had been moved between parishes despite multiple allegations. His testimony was emblematic of a recurring pattern: institutions protected abusers, while victims were left to rebuild themselves alone.

These stories transformed public understanding from abstraction to empathy. They revealed that survivors were not faceless statistics but people still carrying the scars of trust turned into trauma.

Long-Term Impacts: Far Beyond the Moment of Abuse

Clergy abuse often sets off lifelong struggles. Many survivors battle addiction as a coping mechanism for unresolved trauma. Others lose jobs, relationships, or mental health stability. Some detach from religion entirely, while others wrestle with their faith for decades—caught between spiritual longing and spiritual betrayal. The road to healing is rarely linear; it is a process of rebuilding identity, reclaiming trust, and confronting memories many hoped never to revisit.

From Victims to Survivors: Activism and Empowerment

The rise of survivor networks marked a turning point in the crisis. SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests), founded in the 1980s, became a global force for accountability. Local advocacy groups, parish-level reform movements, and—more recently—social media platforms have amplified survivor voices, transformed public narratives, and provided community for those once isolated in silence.

This activism reframed the language of the crisis. Survivors insist on being recognised not merely as victims of something terrible, but as survivors of immense courage, rebuilding life in the aftermath of institutional betrayal. Their resilience forms the moral centre of the Church’s reckoning.

Legal, Financial, and Institutional Fallout

The sexual abuse crisis did not only reshape the moral landscape of the Catholic Church—it transformed its financial stability, legal exposure, public credibility, and internal governance. What began as isolated lawsuits in the 1980s and 1990s grew into one of the most expensive and far-reaching institutional reckonings in modern history. The fallout has been global, but nowhere more measurable than in the United States, Australia, and Europe, where litigation and public inquiries forced the Church into unprecedented levels of transparency and accountability.

Massive Financial Costs: A Restructured Church Economy

In the United States alone, the Catholic Church has paid over $5 billion in settlements, legal fees, therapy support, and related costs between 2004 and 2023. This staggering figure reflects not only the sheer number of cases but also the accumulation of decades of institutional failure. Many of the largest payouts stem from diocesan bankruptcies, a legal strategy used to manage overwhelming liabilities while continuing Church operations.

Australia has seen similar financial pressure. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (1980–2017) estimated the Australian Catholic Church paid more than $200 million in redress, legal expenses, and support services. These numbers continue to grow as more survivors pursue compensation under new legal frameworks that eliminate time limits for reporting abuse.

The financial strain has reshaped Catholic institutions worldwide. Parishes have consolidated or closed, Catholic schools have reduced operations, and dioceses have liquidated property—including historic buildings—to meet settlement requirements. Even Vatican officials have acknowledged the crisis as one of the greatest financial challenges in Church history.

Diocesan Bankruptcy: A New Era of Legal Strategy

More than 40 U.S. dioceses and religious orders have filed for bankruptcy since 2004, including some of the nation’s oldest and wealthiest dioceses. The 2025 bankruptcy filing by the Archdiocese of New Orleans, following years of litigation and over 500 claims, illustrates that even large metropolitan dioceses are not immune to financial collapse.

Bankruptcy proceedings force dioceses to reveal confidential records, identify property assets, and negotiate large collective settlements with survivors. While critics argue bankruptcy protects the Church from full civil exposure, many survivors see it as a path to compensation they would otherwise never receive. These filings also demonstrate how deeply abuse settlements have reshaped the Church's fiscal policy and long-term planning.

Declining Trust: Attendance, Donations, and Credibility

The financial consequences intersect with a profound spiritual and sociological decline. Across North America, Europe, and Australia, Church attendance and donations have fallen sharply since the early 2000s.

- Large numbers of young Catholics cite the abuse crisis as a primary reason for disaffiliation.

- Parish giving dropped significantly in dioceses under investigation or litigation.

- Catholic schools and charities report donor hesitation tied directly to perceptions of institutional dishonesty.

Credibility, once the Church’s greatest intangible asset, has eroded. For many families, the crisis represents a deep moral betrayal, leading to generational disengagement from organised religion.

Insurance and State Legislation: Expanding Legal Exposure

Insurance companies—once major defenders of dioceses—have grown increasingly reluctant to cover claims without transparency requirements. Many insurers demanded documentation of past allegations before renewing policies, putting pressure on dioceses to release previously hidden files.

State legislatures played a key role in widening accountability. Over 20 U.S. states enacted “lookback windows” or permanently removed statutes of limitations, allowing survivors to file claims regardless of when the abuse occurred. These legal reforms triggered waves of new lawsuits, shaping diocesan strategies and accelerating bankruptcy trends.

Institutional Reform: Policies That Changed Church Governance

The crisis forced the Catholic Church into unprecedented structural self-examination. Two major reforms stand out:

The Dallas Charter (2002)

Adopted by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, the charter:

- Mandated zero tolerance for credible offenders

- Required reporting of allegations to civil authorities

- Created lay review boards

- Established youth protection programs

Though imperfect—critics note it initially excluded bishops—the charter dramatically reduced new cases of abuse in the U.S. after 2002.

Vos estis lux mundi (2019, revised 2023)

Issued by Pope Francis, this decree:

- Required all dioceses worldwide to create reporting systems

- Allowed for investigations of bishops

- Set global standards for handling allegations

Its 2023 revision made many protections permanent, signalling the Vatican’s recognition that abuse is a global governance issue, not merely a pastoral problem.

Reform, Resistance, and the Road Ahead

Two decades after the Boston revelations, the Catholic Church has undergone profound change—but not enough to satisfy survivors or restore global trust. The reform journey has been uneven: moments of courage followed by institutional hesitation, bold policies undercut by weak enforcement, and repeated crises that reopened old wounds. The road ahead remains contested, shaped by survivors’ demands, internal resistance, and the Church’s struggle to redefine authority in the 21st century.

The Dallas Charter: A Landmark with Blind Spots

The Dallas Charter of 2002 marked the first major institutional reform in response to the U.S. abuse crisis. It established mandatory reporting, independent review boards, safe-environment training, and a zero-tolerance policy for abusive priests. The Charter dramatically reduced new cases of child abuse in the United States, proving that policy change can make a difference.

But the Charter had a glaring flaw: it did not apply to bishops, the very leaders responsible for reassigning abusers, silencing victims, and protecting offenders. Bishops could discipline priests—but not each other. The loophole created an accountability vacuum that persisted for nearly two decades, fueling survivor anger and allowing several high-profile episcopal scandals, such as the McCarrick case, to fester until public exposure forced action.

Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors: Promise and Turbulence

Pope Francis established the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors in 2014, intended to be a global advisory body shaping policies on safeguarding and survivor outreach. Under figures like Cardinal Seán O’Malley, the Commission helped promote training programs, create safe-environment standards, and encourage bishops’ conferences worldwide to draft uniform guidelines.

Yet progress was undercut by resignations and internal frustration. Survivor-members like Marie Collins stepped down, citing Vatican resistance and bureaucratic indifference. Some dicasteries ignored the Commission’s recommendations. The Commission lacked enforcement power, leaving many observers to conclude that, while symbolic, it struggled to influence the deeper structures that protected abusers.

Pope Francis: A Mixed, Complex Legacy

Pope Francis’s approach to abuse has been defined by powerful gestures mixed with painful contradictions. His public apologies—to survivors in Chile, Ireland, the U.S., and the Philippines—were unprecedented for a pope. His 2019 global summit on the protection of minors brought episcopal leaders from around the world to Rome, signalling that the crisis was no longer a Western issue but a universal moral emergency.

Francis also oversaw major structural reforms:

- Outlawing the “pontifical secret” in abuse cases (2019)

- Expanding definitions of abuse and cover-up

- Issuing Vos estis lux mundi, establishing systems to investigate bishops

Yet his missteps were significant. In Chile, he initially defended bishops accused of covering up abuse before reversing course. His handling of the Rupnik scandal raised questions about double standards for powerful clergy. These inconsistencies undermined his credibility among survivors who felt betrayed by repeated failures to match rhetoric with decisive action.

2023–2025 Reforms Under Pope Leo XIV

The election of Pope Leo XIV in 2023 signalled a renewed push for structural accountability. Early in his pontificate, Leo XIV strengthened Vos estis lux mundi, clarifying investigative timelines, penalties, and oversight for bishops. He authorised unprecedented audits of diocesan safeguarding offices and publicly released summary data on disciplinary actions—a step previous popes avoided.

However, Leo XIV has also faced controversy. Critics claim his reforms rely too heavily on internal Church mechanisms rather than independent oversight. Some bishops have resisted new guidelines, arguing they infringe on episcopal authority. Survivors remain cautiously optimistic but unconvinced that internal reform alone can address systemic failures.

Survivor Distrust and Calls for True Accountability

Despite reforms, survivors remain the Church’s most consistent moral critics. They demand:

- Transparent release of personnel files

- Financial reparations without legal obstruction

- Independent investigations, not supervised by bishops

- Criminal prosecution of cover-ups

Many survivors argue that until bishops who protected abusers face real consequences—canonical, legal, and financial—the Church cannot claim meaningful reform.

Sociological Shifts: A Church at a Crossroads

The crisis has reshaped the Catholic Church’s social structure. Vocations to the priesthood continue to decline, especially in the West. Lay Catholics—once deferential—now demand shared governance, financial transparency, and oversight roles in safeguarding.

Some propose new models:

- Lay-led diocesan boards with investigative authority

- Mandatory reporting laws are enforced within canon law

- Regional truth commissions

- Synodal structures that reduce clerical dominance

These proposals reflect a Church transitioning toward stronger lay involvement, though resistance from traditionalists remains fierce.

The Future: Unfinished Work

Reform has begun, but accountability is far from complete. The path forward will require honesty, independent oversight, global uniformity, and the courage to dismantle systems that once protected power instead of people. Survivors continue to lead the way—testimony by testimony—insisting that the Church’s future must be built on justice, not secrecy.

Conclusion: Faith After the Fall

The Catholic Church's sexual abuse crisis is not merely a historical event or institutional scandal. It is a profound moral rupture—one that forces a timeless question: Can a moral institution survive its own moral failure? The answer depends not only on structures, reforms, or policies, but on the Church’s willingness to confront the truth with humility, courage, and unwavering commitment to those it once failed to protect.

The lessons of the past half-century cut sharply across themes of power, secrecy, and institutional ethics. Abuse flourished not simply because individual priests committed crimes, but because systems of authority protected them. Clericalism, deference, and a culture that valued reputation over responsibility created the perfect conditions for harm. Files were hidden, victims were silenced, and truth was treated as a threat rather than a guide. This crisis reveals a universal truth about institutions: when power operates without transparency, human dignity becomes vulnerable.

Yet even in the darkest chapters of this story, the light has come from survivors. Their courage—whether spoken through courtroom testimony, investigative interviews, or quiet conversations with community groups—became the catalyst for global change. It was survivors, not bishops, who exposed patterns of cover-up. It was survivors who pushed lawmakers to lift statutes of limitation. It was survivors whose stories shattered the illusion of infallible authority and forced the Church, governments, and societies to reckon with uncomfortable truths.

Their voices now form the moral compass of reform. The Church’s credibility, though deeply damaged, need not be permanently destroyed. Institutions can transform when they embrace accountability, prioritise protection over prestige, and centre the wounded rather than the powerful. The path forward is not about dismantling faith but purifying it—recognising that true spiritual authority is measured not by titles or vestments but by integrity, compassion, and justice.

Today, the Church stands at a crossroads. One path leads to defensiveness, nostalgia, and slow decline. The other leads to transparency, shared leadership, and authentic humility. The choice will determine not only the Church’s institutional future but its spiritual relevance in a world increasingly sceptical of authority.

In the end, the crisis teaches a simple, enduring truth: faith demands truth — not silence. Silence wounds; truth heals. Silence protects institutions; truth protects children. If the Church chooses truth—consistently, courageously, and globally—it may yet emerge from this era not as it once was, but as it should have been all along.

References — Authoritative Source Links

John Jay College Reports

- The Nature and Scope of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests in the United States (1950–2002)

- The Causes and Context of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests (2011)

The Boston Globe Spotlight Investigation (2002)

Australia — Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017)

Ireland — Ryan Report (2009) & Murphy Report (2009)

Vatican Documents

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child — Vatican Report (2014)

Marcial Maciel & Legion of Christ

Global Reports on Abuse of Nuns (1994–1998)

Financial Impact and Bankruptcy Cases

- USCCB Financial Summary of Abuse Settlements

- National Catholic Reporter database of diocesan bankruptcies

Survivor Testimonies

Academic Works and Books

- Jason Berry, Lead Us Not into Temptation (1992) Publisher

- Richard Sipe, Sex, Priests, and Power

- Marie Keenan, Child Sexual Abuse and the Catholic Church (Oxford University Press)

International Abuse Data

- Amnesty International reports on institutional sexual abuse

- Human Rights Watch (global clerical abuse documentation)