Introduction – Origins, Meaning, and Contemporary Relevance

Historical Background of Hong Kong’s Flags Before 1997

Before the adoption of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region flag in 1997, the territory’s identity was visually represented through a series of colonial-era ensigns that symbolised British imperial authority. These flags, primarily variants of the British Blue Ensign, provide essential historical context for understanding the significance of Hong Kong’s post-colonial flag. For much of its colonial history, Hong Kong’s flag consisted of a dark blue field bearing the Union Jack in the upper left corner and a localised emblem on the fly side. This emblem evolved over time, beginning with a simple badge and later advancing into a more detailed coat of arms incorporating imagery of a crowned lion, a dragon, and maritime symbols. These elements collectively expressed the region’s strategic importance as a port and a British-controlled gateway into Asia.

The symbolism of the colonial flag reflected both governance and commerce. The Union Jack signalled imperial sovereignty and integration into the British Commonwealth, while the localised emblems projected Hong Kong’s role as a commercial hub connecting Chinese markets with global trade routes. Maritime features in the emblem—ship imagery, waves, and coastal motifs—mirrored the colony’s economic foundations in shipping, logistics, and mercantile exchange. To the colonial administration, this design communicated legitimacy and authority; however, it did not necessarily reflect the cultural identity of Hong Kong’s majority population, who were ethnically Chinese and culturally distinct from the British metropole. Rather than being a shared emblem of local belonging, it served largely as a governmental and administrative symbol.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, as Britain and China entered discussions over Hong Kong’s future, the status of the colonial flag gradually became a subject of political and symbolic transition. The Sino–British negotiations leading to the 1984 Joint Declaration foregrounded questions of sovereignty, autonomy, and identity, prompting early conversations about the need for a new flag that could represent Hong Kong beyond colonial authority. During this period, some political groups and public figures began to see the Blue Ensign as outdated—an artefact of external rule rather than a symbol of the city’s character. Others, particularly those who feared political change, still felt a sentimental attachment to the flag as a representation of stability and internationalism.

Public sentiment in the final decades of British administration was deeply mixed. For some residents, the colonial flag served as a reminder of relative freedoms—rule of law, economic openness, and separation from mainland politics. For others, especially pro-democracy advocates and younger generations, it inadequately captured Hong Kong’s complex identity and growing aspirations for self-definition. Meanwhile, Beijing viewed the colonial symbols as temporary placeholders that would inevitably be replaced upon the return to Chinese sovereignty.

By the time of the handover, the Blue Ensign no longer functioned as a neutral emblem; it had accumulated layered meanings tied to memory, expectation, and apprehension. The necessity of a new flag for the Hong Kong SAR became clear not only as a legal requirement of the pending sovereignty shift, but also as a cultural and emotional transition. The creation of the Bauhinia flag in the 1990s was therefore not an isolated act of design—it was a deliberate step in replacing a symbol rooted in imperial authority with one meant to signal a new era.

Thus, understanding the colonial flags before 1997 is essential: they were symbols of external rule, commercial identity, and political ambiguity. Their evolution set the stage for the emergence of the SAR flag, which sought to convey a new identity grounded in the principles of reunification, autonomy, and the complicated promises of “One Country, Two Systems.”

The Road to the HKSAR Flag: Design Proposals and Selection Process (1990–1996)

The creation of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) flag was neither a spontaneous design effort nor a simple artistic exercise. Instead, it was the product of a six-year process shaped by political negotiation, symbolic messaging, and strategic cultural presentation during the final phase of British–Chinese transition. Between 1990 and 1996, the design evolved through multiple drafts, committee evaluations, and ideological adjustments until it became the emblem unveiled at the moment of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty on 1 July 1997.

The first public emergence of what would become the HKSAR flag occurred in April 1990, when an early version of the now-familiar Bauhinia design was introduced at the National People’s Congress (NPC) in Beijing. This event signalled China’s intention to establish a visual identity for post-colonial Hong Kong long before the official handover date. The timing was deliberate: it coincided with the ongoing drafting of the Basic Law, the constitutional framework that would define Hong Kong’s governance after 1997. By revealing the design during a major legislative session, Beijing conveyed that the regional flag was more than a decorative symbol; it was a structural component of the new constitutional order.

Multiple political bodies influenced the development of the flag. The National People’s Congress (NPC) played the central approving role, while the Basic Law Drafting Committee evaluated the symbolic and constitutional appropriateness of proposed elements. The Hong Kong Preparatory Committee, composed of representatives from both Hong Kong and the mainland, helped shape the design from a local governance perspective. These groups debated not only aesthetics but the communicative power of specific details: colours, shapes, botanical imagery, and the presence of stars. Their involvement ensured that the flag aligned with Beijing’s expectations of sovereignty while appearing locally relatable rather than imposed.

At the heart of the design process was Tao Ho, a respected Hong Kong architect and cultural figure. His artistic influence was central to the final outcome. Ho sought a design that preserved artistic elegance while functioning as a symbol of political transition. He selected the Bauhinia blakeana, a flower native to Hong Kong, because it represented a neutral botanical emblem without direct colonial association. This made it a culturally authentic symbol—rooted in Hong Kong’s landscape rather than empire or ideology. Ho’s layout of the flower, with five petals rotating outward in a symmetrical formation, was carefully calculated to evoke visual balance and a sense of forward motion, subtly implying continuity rather than rupture.

During the early 1990s, multiple alternative proposals were considered. Some designs incorporated hybrid iconography that combined Chinese national elements with Hong Kong imagery, such as dragons, harbours, city skylines, or stylised junks representing trade. Other drafts explored traditional Chinese decorative styles or Western graphic approaches meant to reflect Hong Kong’s international character. These proposals were rejected for several reasons: some appeared too colonial or Western in tone, others too nationalistic to represent Hong Kong’s semi-autonomous status. A few designs were dismissed because they visually competed with the national flag, while others failed to capture the desired emotional neutrality. The ultimate goal was not triumphalism but a sense of dignified renewal.

By 1996, a final version was selected and formally approved. The red background, matching the tone of the Chinese national flag, underscored sovereignty and national belonging. The five stars, placed within the flower petals, echoed the stars of the national flag without duplicating them. This detail communicated political unity in a visual language that remained distinct to Hong Kong. The red-and-white contrast further highlighted a conceptual balance: national identity surrounding and supporting local identity. As preparations began for the 1997 handover ceremony, the finalised flag was reproduced under strict regulation, ensuring consistency of colour, dimensions, and orientation. The image became central to rehearsals for the handover event, where both the Chinese national flag and the Hong Kong SAR flag would be raised side by side for the first time.

Ultimately, the design process from 1990 to 1996 reveals that the HKSAR flag was created to accomplish multiple objectives at once. It needed to symbolise political reunion without erasing Hong Kong’s uniqueness, reflect national authority without replicating the national emblem, and evoke cultural familiarity without invoking colonial memory. The Bauhinia on red fulfilled these requirements. Through aesthetic restraint and political intentionality, the flag became an emblem suited to a territory standing at the threshold of historical transformation—local in imagery, national in meaning, and deeply shaped by the negotiations that produced it.

Detailed Analysis of the Flag’s Design and Symbolism

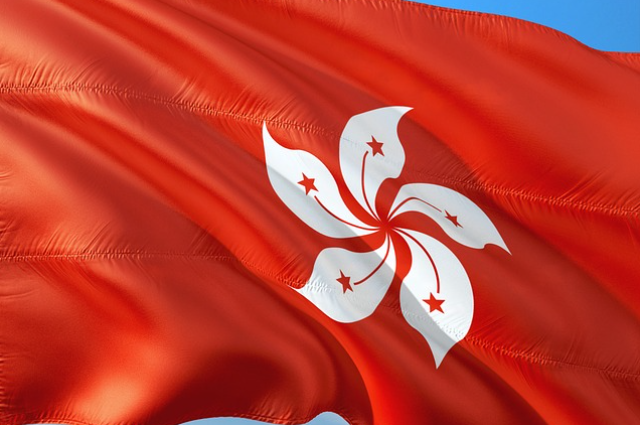

The flag of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is a carefully engineered symbol in which aesthetics, ideology, and cultural identity intersect. Rather than functioning as a neutral piece of design, the flag communicates layered messages about Hong Kong’s political status, historical trajectory, and intended national relationship. Every visual element—from its colours to its geometry—carries deliberate meaning, reflecting both traditional Chinese symbolism and Hong Kong’s distinct social character under the framework of “One Country, Two Systems.”

The red field is the most immediately recognisable symbolic component. Its colour matches the red of the national flag of the People’s Republic of China, an intentional choice that visually anchors Hong Kong within the Chinese national space. In Chinese cultural tradition, red is associated with celebration, prosperity, and collective identity, often used in festivals, weddings, and state ceremonies. Politically, it represents revolution, sovereignty, and national unity. On the Hong Kong flag, the red field establishes the backdrop of belonging: it signals that Hong Kong is part of the Chinese nation while preserving a degree of symbolic space for the region’s unique identity. The background, therefore, serves as both a statement of authority and a cultural gesture, positioning Hong Kong within a shared national narrative rather than as an isolated jurisdiction.

At the centre of this red field sits the white Bauhinia blakeana, a five-petaled flower native to Hong Kong. The choice of this flower was foundational to creating a symbol that felt local, rooted, and culturally neutral. Unlike colonial icons or overtly political symbols, the Bauhinia is tied to Hong Kong’s environment, as the species was discovered and cultivated in the territory. Its white colour symbolises purity, openness, and clarity, contrasting with the assertive red of the background. The contrast visually emphasises that Hong Kong maintains an identity separate from, but not in opposition to, mainland China. The flower becomes a metaphor for civic identity—representing Hong Kong as a socially distinct community with its own culture, legal system, and lived reality.

Embedded within each petal is a red, five-pointed star, mirroring the larger stars found on China’s national flag. These stars represent unity with the nation and symbolise the connection between Hong Kong and the broader Chinese state. Their placement inside the petals is a nuanced decision: rather than surrounding or overshadowing the flower, the stars appear integrated within it. This detail visually expresses a relationship in which sovereignty encompasses but does not erase local identity. The number five itself holds symbolic meaning in Chinese tradition, often associated with balance, harmony, and the five elements—a subtle reinforcement of unity through cultural symbolism. Consequently, the flower and stars together form a visual statement of constitutional principle: identity within sovereignty, autonomy within structure.

The flag’s geometrical structure enhances these messages through carefully calculated balance. The proportions follow a 2:3 ratio, the same as the Chinese national flag, providing visual consistency when flown side by side. The Bauhinia’s petals radiate clockwise with even spacing, creating a sense of movement and continuity rather than static symbolism. This rotational symmetry suggests a forward-looking identity, reflecting Hong Kong’s international orientation and modern economy. The scale of the emblem relative to the field—large enough to dominate the centre but not oversized—reinforces the idea of coexistence rather than contestation between local and national identities.

Colour theory also plays a role. The white Bauhinia against the red field generates a high-contrast composition that is both striking and harmonious. From a symbolic standpoint, the colours suggest duality: red conveys the collective and national, white conveys individuality and transparency. Visually, this alludes to the coexistence of Chinese nationality and Hong Kong’s distinct civic culture. Practically, the contrast enhances visibility on government buildings, maritime vessels, border checkpoints, and international venues, ensuring easy recognition and consistent representation.

Underlying these elements is an intentional message aligned with the policy framework of the post-1997 era: “Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong.” While the phrase itself represents political aspiration rather than pure artistic interpretation, the flag’s design mirrors this idea symbolically. The Bauhinia—local, soft, and culturally specific—occupies the centre, while the red field and stars communicate national authority. The composition does not depict opposition but coexistence, visually encoding the constitutional promise that Hong Kong would retain certain systems and characteristics while remaining part of a larger sovereign state.

In many national flags, design choices are either symbolic or functional; in Hong Kong’s case, they are deliberately both. The SAR flag becomes a visual negotiation between identity and authority: a red field of sovereignty, a white flower of locality, and stars of national belonging. Its symbolism is not fixed but contingent, shaped by cultural interpretation and political climate. As a result, the Bauhinia banner stands not merely as a regional emblem, but as a complex visual statement of what Hong Kong was meant to be—distinct yet connected, autonomous yet integrated, and culturally hybrid at the centre of two intersecting worlds.

Legal Framework and Protocols Governing the Flag

The flag of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) is not merely a visual emblem—it is legally protected and regulated under Hong Kong law. The Basic Law, Hong Kong’s constitutional document, expressly permits the use of regional symbols alongside national symbols, and local ordinances provide detailed rules on how the flag must be produced, displayed, and respected. These legal frameworks aim to safeguard the dignity of the flag while balancing freedom of expression and statutory restraints.

Hong Kong Basic Law and Regional Symbols

Article 13 of the Basic Law allows the HKSAR to adopt its own regional flag and emblem and to formulate laws governing their use. It states that, alongside the national flag of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the regional flag and emblem shall be used in Hong Kong as the symbols of the region. This constitutional provision situates the Hong Kong flag within the legal order of the SAR, affirming its official status and outlining its relationship with national symbols.

Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance (1997; Amended 2020 & 2023)

The Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance (RFREO) came into effect on 1 July 1997, the day Hong Kong returned to Chinese sovereignty. Its core purpose is to legally protect and regulate the use of the regional flag and emblem. The ordinance has been amended over time to strengthen protections and clarify definitions, with a significant updated version promulgated in November 2023 to align it with other laws such as the National Flag and National Emblem Ordinance.

Under the ordinance:

- The specifications for the flag’s design—dimensions, colour, and construction—are detailed in a schedule attached to the law and must be strictly followed by manufacturers. Producing non-compliant flags is subject to legal action, including injunctions and forfeiture of materials.

- The Chief Executive has the authority to stipulate where, when, and how the flag and emblem must be displayed and may restrict certain uses of the design.

- Flags that are damaged, defaced, faded, or substandard must not be used or displayed, ensuring that only dignified representations of the flag are presented publicly.

Regulations on Display, Disposal, and Etiquette

The amended ordinance includes provisions for responsible handling and disposal of flags. Event organizers are required to collect and return damaged or used flags to designated collection points, preventing misuse or disrespectful disposal. The law also clarifies etiquette for flag-raising ceremonies, emphasizing solemn and respectful conduct during official events where the regional flag is flown.

In addition, protocol guidelines (published by the Protocol Division of the Government Secretariat) specify that flags must not be displayed upside down or in a manner that undermines their dignity. Flags should be used in ways that convey respect and must adhere to government stipulations.

Penalties for Misuse and Desecration

One of the most stringent protections in the RFREO relates to desecration of the regional flag. Section 7 of the ordinance criminalises acts such as publicly and wilfully burning, mutilating, scrawling on, defiling, or trampling the flag. Conviction may result in a fine and, historically, imprisonment of up to three years—a penalty that mirrors provisions for the national flag.

The law also prohibits using the flag or its design in trademarks or advertisements without authorisation. Unauthorised or frivolous commercial or decorative use of the flag is treated as an offence under the ordinance.

Additionally, any item that closely resembles the flag so as to be confused with it is treated as the flag under the law. This broad definition prevents circumvention of legal protections through altered designs.

Protocols During Ceremonies and Official Occasions

Flag-raising and lowering at official ceremonies follow set protocols. During formal events—such as Establishment Day (1 July), National Day (1 October), and other government functions—the Hong Kong regional flag is raised alongside the PRC national flag, with specific orders of precedence and respectful conduct required. These protocols are outlined in both legislation and government ceremonial guides.

Comparative Perspective

Like many countries, Hong Kong has specific laws protecting national and regional symbols. For example, some Western nations criminalise flag desecration, while others treat such acts as protected political speech. Hong Kong’s approach reflects a balance between respecting symbolic dignity and legal order, positioning it closer to jurisdictions that assign statutory responsibility to protect flags from defacement and misuse—especially in contexts where national identity is highly sensitive.

In sum, the legal framework governing Hong Kong’s regional flag combines constitutional authorisation with detailed statutory rules on manufacture, display, etiquette, and protection. Through ordinances and protocol guidelines, the SAR seeks to ensure that its flag is treated with dignity and respect while remaining integrated into Hong Kong’s legal and civic life.

The Flag in Sociopolitical Context: Identity, Loyalty, and Public Sentiment

Since its adoption in 1997, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) flag has occupied an uneasy place in public consciousness—honoured in official settings but contested in the streets, classrooms, and digital arenas. In post-handover Hong Kong, the flag has become both a symbol of civic pride and, for many, a marker of political tension and identity conflict.

For supporters of the SAR government and those who emphasise Hong Kong’s constitutional position within China, the flag represents legal continuity, national unity, and regional distinction. In official ceremonies such as Hong Kong Establishment Day (1 July) and China’s National Day (1 October), the Hong Kong flag is raised alongside the Chinese national flag to visually communicate the co-existence of regional autonomy with national sovereignty—a key promise of the “One Country, Two Systems” framework. These ceremonial uses are designed to foster patriotism and respect for constitutional order, and the flag increasingly features in patriotic education campaigns aimed at reinforcing a shared sense of citizenship within the Chinese nation.

However, public attitudes toward the flag vary significantly across social groups. Older generations and business sectors, which often prioritise stability and economic continuity, are more likely to view the flag in neutral or positive terms, associating it with Hong Kong’s stability, legal system, and prosperity over the past decades. Their engagement with the flag is more formal, tied to official functions, public institutions, and Asian-Pacific economic identity rather than political movements.

By contrast, for many youth and pro-democracy activists, the flag has become entangled with broader concerns over political freedoms and local identity—especially after mass movements such as the 2014 Umbrella Movement. During the Umbrella Movement, which erupted as protests demanding genuine universal suffrage, a distinct sense of Hong Konger identity emerged among young participants. Many young people began to identify primarily as “Hongkongers” rather than “Chinese,” a shift documented by identity surveys showing generational differences in self-identification. Younger cohorts were far more likely to express a local Hong Kong identity, whereas older residents tended toward broader Chinese identity labels.

Although the SAR flag itself was not a central symbol during the Umbrella Movement, the broader context of political activism influenced how people perceived official symbols. The movement’s focus on democratic reform and autonomy led to increased scepticism toward any symbols perceived as representing mainland authority—even if legally distinct. In subsequent years, this sentiment laid the groundwork for more overt symbolic adaptations.

The 2019–2020 protests against the proposed extradition bill marked a significant shift in how the Hong Kong flag was used—or rejected—in public discourse. Many protesters viewed the official flag as symbolic of the political status quo and the limits of autonomy under Beijing’s influence. As a result, alternative or subversive flag imagery gained prominence. Most notable among these was the “Black Bauhinia”, a modified version of the HKSAR flag with a black field and altered flower motifs. The Black Bauhinia was adopted by pro-democracy demonstrators as a visual critique of the perceived erosion of freedoms and a metaphor for the withering away of the promised autonomy; its black background and modified petals symbolised mourning and resistance.

Beyond local streets, symbolic interpretations have also spread internationally. Members of the Hong Kong diaspora have used versions of protest flags in rallies and cultural events abroad, framing them as emblems of ongoing resistance and identity preservation amid growing diaspora communities.

These varied uses reflect divergent interpretations of the same symbol. To pro-establishment groups, the SAR flag continues to signal legal identity and privileged autonomy within the Chinese nation. To many youth and pro-democracy advocates, however, the flag’s official form is seen as insufficiently representative of personal and political aspirations—prompting creative adaptations or outright alternatives that emphasise local distinctiveness or critique central authority.

Over time, public perception of the flag has therefore shifted from a relatively straightforward official emblem to a contested cultural symbol—one that encapsulates deep tensions over identity, governance, and belonging in post-handover Hong Kong. As the city’s political landscape continues to evolve, the flag’s symbolic resonance will likely remain a focal point in debates over autonomy, citizenship, and collective memory, challenging simplistic readings of national unity and regional identity.

The Emergence of the Black Bauhinia: Protest Symbolism (2019–2020)

The Black Bauhinia flag emerged as one of the most potent visual symbols during the 2019–2020 Anti–Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) protests in Hong Kong. Its origin lies in a deliberate modification of the official Hong Kong SAR flag: the familiar red background was replaced with black, while the white Bauhinia flower was sometimes altered or depicted as damaged. This design shift was not aesthetic alone; it carried profound political and emotional significance, encapsulating a period of civic unrest and widespread disillusionment.

The Black Bauhinia became a symbol of resistance and mourning. Its darkened background visually signified grief over the perceived erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms, the failure of governmental accountability, and the threat to the region’s promised autonomy under the “One Country, Two Systems” framework. Protesters used the flag to communicate both personal and collective despair, marking the transition from peaceful demonstration to confrontational activism. Its visual contrast to the red SAR flag—officially sanctioned and tied to state authority—highlighted the identity crisis felt by many young Hongkongers, who increasingly saw themselves as culturally distinct from the mainland while still inhabiting its territory.

The flag appeared extensively in protests, rallies, and digital media campaigns. Activists carried it alongside slogans and banners calling for democratic reform, the protection of civil liberties, and the resignation of perceived complicit officials. Its design, simple yet emotionally charged, allowed it to function as a unifying symbol for the decentralised movement, giving visual cohesion to a loosely organised protest network. In some cases, the flower’s petals were deliberately defaced, bloodied, or depicted as wilting, amplifying the sense of injustice and urgency conveyed by demonstrators.

The Hong Kong government interpreted the Black Bauhinia as an illegal misuse of the official SAR flag, falling under the protections outlined in the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance. Officials warned that public display of the altered flag could constitute desecration, with potential criminal liability including fines or imprisonment. Authorities framed it as a symbol of subversion, equating its public use with challenges to state sovereignty and social order. This response underscored the symbolic stakes of the flag: beyond being a visual marker, it became a legal and political instrument, mediating contestation over identity, legitimacy, and loyalty.

Internationally, the Black Bauhinia attracted significant media attention. Global news outlets frequently featured images of the flag during protests, interpreting it as a signal of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy aspirations and growing local discontent. For observers outside China, it came to represent not only resistance to mainland influence but also a broader struggle over civil liberties and autonomy in the modern city-state. Its circulation on social media further amplified its symbolic power, making it a recognisable emblem of Hong Kong’s political crisis even among audiences unfamiliar with local governance structures.

In sum, the Black Bauhinia flag functioned as both a cultural and political icon. It contrasted sharply with the official red SAR flag, communicating grief, resistance, and identity assertion. Its use highlighted the tension between official legal authority and grassroots political expression, while internationally it became a symbol through which Hong Kong’s ongoing struggle over autonomy and freedom was visually narrated. In the context of the 2019–2020 protests, the flag demonstrated how symbolic adaptations can crystallise collective sentiment, transforming a regional emblem into a powerful instrument of civic discourse and global attention.

Global Reception and Comparative Perspectives

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) flag has attracted international attention not only as a regional symbol but also as a barometer of political and social dynamics within the territory. Globally, the flag is recognised for its distinctive Bauhinia emblem, conveying both Hong Kong’s local identity and its connection to China. In diplomatic and international contexts—such as at consulates, trade fairs, or multinational conferences—the flag signals Hong Kong’s semi-autonomous status, reminding observers of its unique governance under the “One Country, Two Systems” framework. Its symbolism, however, has evolved in tandem with local political tensions, particularly following the 2014 Umbrella Movement and the 2019–2020 protests, which introduced alternative interpretations such as the Black Bauhinia.

Comparative perspectives highlight the complexities of regional or semi-autonomous flags. For instance, Macau, another SAR, uses a lotus emblem on a green and white background to express local identity within China, paralleling Hong Kong’s emphasis on native symbolism. Internationally, flags such as Quebec’s fleur-de-lis or Scotland’s Saltire similarly represent cultural identity and political autonomy within larger states, illustrating a global pattern where subnational symbols serve both civic pride and political communication.

The Hong Kong diaspora has played a key role in circulating alternative flag meanings abroad. Protesters and expatriates often display the Black Bauhinia at rallies, cultural events, and online campaigns, framing it as a symbol of resistance, democracy, and local identity. These international displays amplify Hong Kong’s struggles and extend the flag’s significance beyond the SAR’s borders, transforming it into a global emblem of civic discourse, contested sovereignty, and cultural distinctiveness.

Conclusion – The Future of the Bauhinia Banner

Since its official adoption in 1997, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region flag has evolved from a largely neutral symbol of regional autonomy into a contested emblem charged with political, cultural, and emotional significance. Initially, the red field and white Bauhinia projected a vision of harmonious coexistence between Hong Kong’s distinct civic identity and its integration within the People’s Republic of China. The flag symbolised the promises of the “One Country, Two Systems” framework: a visual reassurance that Hong Kong would retain unique social, legal, and cultural characteristics while remaining part of the national fabric.

Over the decades, however, socio-political shifts—including the Umbrella Movement in 2014 and the Anti-Extradition protests in 2019–2020—transformed public perceptions. To many residents, the official SAR flag became a symbol of authority, compromise, or contested sovereignty, prompting the emergence of alternative representations such as the Black Bauhinia. These adaptations reflected growing tensions between national integration and local identity, highlighting the flag’s capacity to convey divergent interpretations depending on political orientation, generational perspective, and civic engagement.

Looking ahead, the Bauhinia banner will continue to embody these tensions. Its meaning is likely to remain fluid, shaped by evolving policies, civic movements, and international attention. While the official flag will persist as a legally protected emblem of Hong Kong’s status within China, grassroots reinterpretations may continue to emerge, reflecting local identity, civic aspirations, and resistance to perceived encroachments on autonomy. Ultimately, the SAR flag is more than a ceremonial symbol; it is a living icon of Hong Kong’s ongoing negotiation between tradition, modernity, and political belonging—a banner whose future significance will evolve alongside the city it represents.

References

Official and Factual Sources

- Flag of Hong Kong (Wikipedia) – Overview of the flag’s design, adoption history, Basic Law context, and protest variants. Flag of Hong Kong – Wikipedia

- Hong Kong Protocol Division (Govt.) – Specifications of the SAR flag and examples of proper display and etiquette. National and Regional Flags & Emblems (Protocol Division)

- Education Bureau – Flag Raising & Etiquette – Details on flag design and ceremonial protocols. National Anthem and Regional Flag – Education Bureau

- Hong Kong Info Gov HK – RFREO Amendment (2023) – Latest amendments to the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance emphasising respect and legal protection. Regional Flag and Regional Emblem (Amendment) Ordinance – HK Gov Press Release

- Education Bureau Official Reply – Information on education and ceremonial use of the flag in schools. LCQ on Education in the National and Regional Flag

Protest‑Related References

- Black Bauhinia Flag (Wikipedia) – History and use of the protest variant during the 2019–2020 movement. Black Bauhinia Flag – Wikipedia

- Alternative Source on Black Bauhinia and Legal Context – Discusses enforcement actions and legal interpretations related to protest flag use. Black Bauhinia Variant & Legal Issues

Constitutional & Legal Context

- Basic Law Article on Regional Symbols – Constitutional basis for the regional flag and emblem in Hong Kong. Basic Law on Use of Regional Flag and Emblem (China Daily summary)

- Legislative Council Documents – Details of amendments and protections under the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance. LegCo Bill Papers on Regional Flag & Emblem Law