Introduction

At the height of America’s cultural revolution, when the promises of peace, freedom, and artistic rebellion seemed to redefine an entire generation, a series of brutal murders in August 1969 shattered the illusion of a hopeful era. The killings at Cielo Drive and the LaBianca residence—later collectively known as the Tate–LaBianca murders—were not merely acts of violence; they were a symbolic rupture in the national psyche. At a time when the country was already strained by war, racial tensions, and generational conflict, the crimes delivered a chilling message: even the most idyllic visions of the 1960s were vulnerable to darkness.

What made these murders stand out was not only their savagery, but the identity of their victims and the bizarre ideology behind them. The death of actress Sharon Tate, a rising Hollywood star and the pregnant wife of celebrated filmmaker Roman Polanski, brought the tragedy directly into the world of celebrity. Suddenly, violence was not something that happened in distant neighbourhoods or criminal underworlds—it had invaded the homes of the cultural elite. The randomness, cruelty, and theatricality of the crimes created a shockwave far beyond Los Angeles, gripping the entire nation.

The story that unfolded in the following months revealed something even more unsettling: these murders were carried out not by seasoned criminals, but by young followers of a charismatic cult leader named Charles Manson. Their actions were rooted in a strange blend of apocalyptic prophecy, racial paranoia, psychological manipulation, and distorted countercultural ideals. As the media exposed the inner workings of the so-called “Manson Family,” a narrative emerged that forever altered the way America viewed the hippie movement, communal living, and radical youth culture.

The murders of August 1969 marked the symbolic end of the 1960s dream—replacing idealism with fear, and leaving behind a story that continues to fascinate, disturb, and warn.

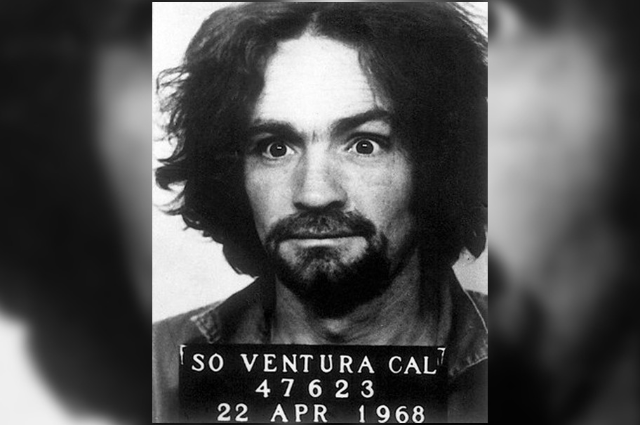

Charles Manson: The Making of a Cult Leader

Early Life and Repeated Incarceration

Charles Manson’s evolution into one of America’s most infamous cult leaders began long before he stepped into the countercultural landscape of the late 1960s. Born in 1934 to a teenage mother who struggled with alcoholism and instability, Manson’s childhood was marked by abandonment, transience, and emotional neglect. He spent much of his youth shuttling between relatives, foster homes, and reform institutions, quickly learning that manipulation and petty crime were more reliable survival tools than trust or attachment.

By his teenage years, Manson was already entangled in a long chain of criminal behaviour—burglary, auto theft, check fraud, pimping—each offence pushing him deeper into the criminal justice system. Reform schools and juvenile centres did little to correct his path; instead, they hardened him. In these institutions, he learned dominance, deceit, and the psychological games required to manipulate both peers and authority figures. Prison became his default environment, and by the time he was released in 1967, he had spent more than half his life behind bars.

Psychologically, Manson displayed a troubling combination of traits: an ability to read and exploit the insecurities of others, a superficial charm that masked deep narcissism, and a talent for twisting vulnerability into loyalty. He was a classic example of a manipulative, antisocial personality—capable of captivating followers while lacking empathy for their suffering. These personality traits would become the foundation of his later influence.

Musical Ambitions and the Hollywood Connection

When Manson was paroled during the height of the “Summer of Love,” he emerged into a society undergoing massive cultural transformation. The counterculture’s rejection of authority, embrace of communal living, and fascination with Eastern spirituality provided fertile ground for someone like him. Reinventing himself as a wandering prophet, Manson pursued what he believed was his true destiny: becoming a rock star.

Music wasn’t just a hobby for Manson; it was the centrepiece of his self-image. He believed the Beatles were communicating directly with him through their White Album, particularly songs like “Helter Skelter,” “Piggies,” and “Revolution 9”—tracks he later reinterpreted as apocalyptic prophecies predicting a coming race war. His ambitions were more than delusion; they were a powerful recruitment tool. Many young followers were drawn not only to his mysticism but also to the idea that they were participating in the creation of a revolutionary new sound.

Manson’s proximity to Hollywood came through Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys, who picked up two of Manson’s female followers while hitchhiking and was soon hosting the entire “Family.” Manson charmed Wilson with music, drugs, and sexual access to his followers, eventually moving into Wilson’s home for months. Through Wilson, Manson met influential producer Terry Melcher and believed he was on the verge of a recording contract. When Melcher ultimately rejected him, Manson felt humiliated—a rejection that later played a significant role in his decision to send his followers to the house on Cielo Drive, where Melcher once lived.

Personality and Control Mechanisms

Manson’s power within the Family did not come from physical intimidation alone—it came from a cultivated persona designed to attract lost, searching, or vulnerable young people. He blended fragments of Scientology, Eastern philosophy, prison-learned manipulation techniques, and psychedelic mysticism into a makeshift spiritual doctrine. He offered unconditional acceptance, only to gradually replace his followers’ identities with his own worldview.

Love-bombing was one of his most effective tools: followers were showered with affection, attention, and a sense of belonging they often lacked elsewhere. LSD-fueled “sermons” allowed him to alter their perceptions while reinforcing his authority. During these sessions, Manson presented himself as a saviour, a messiah, and the sole interpreter of truth. Over time, he isolated the group from outside influences, redefined morality, and positioned obedience as enlightenment.

The result was a cult dynamic in which Manson’s word became absolute law. Through psychological manipulation, emotional dependency, and an authoritarian structure cloaked in spiritual language, he transformed ordinary young adults into instruments of his apocalyptic fantasies—eventually culminating in one of the most shocking crime sprees in American history.

Formation of the Manson Family Commune

Haight-Ashbury Beginnings (1967)

When Charles Manson walked out of federal prison in 1967, he entered a world undergoing a cultural transformation. The Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco had become the epicentre of the hippie movement—a place defined by psychedelic experimentation, communal living, and a rejection of mainstream values. Young people from across the country arrived seeking freedom, identity, and belonging. For someone with Manson’s manipulative instincts, this environment was a recruiting ground filled with emotionally vulnerable individuals adrift from their families and conventional structures.

Manson positioned himself as a gentle philosopher with a message of love and liberation. His soft-spoken manner, guitar playing, and laid-back charm helped him attract young women who were searching for purpose or escape. Many were estranged from their parents, disillusioned with society, or experimenting with drugs and free love. Manson offered them exactly what they craved: acceptance, attention, and the promise of a new kind of family. His earliest followers—such as Mary Brunner, Susan Atkins, and Patricia Krenwinkel—joined him not because of coercion, but because his affection-filled approach made them feel uniquely valued. This was the psychological foundation on which the Manson Family was built.

Communal Living at Spahn Ranch

After drifting through various communes and road trips, the group eventually settled at Spahn Ranch, an ageing movie set in the dusty hills outside Los Angeles. Owned by 80-year-old George Spahn, the ranch provided isolation, freedom from outside scrutiny, and enough space for Manson to construct his own miniature society. In exchange for lodging, the women in the group cared for Spahn, cooking, cleaning, and offering companionship, while the men maintained the property.

Life at the ranch was a blend of chaos and ritual. Days were filled with scavenging for food, taking LSD, practising music, performing chores, and engaging in group sexual activities that reinforced communal bonding while eroding personal boundaries. Manson exerted complete authority, dictating everything from sleeping arrangements to romantic relationships. Followers surrendered their individuality to serve what they believed was a higher purpose—one that Manson carefully shaped. Through constant repetition, group discussions, and drug-fueled “lessons,” he framed himself as a spiritual teacher whose insights transcended ordinary reality.

Isolation amplified his influence. Away from families, jobs, and societal norms, his followers came to rely on one another and on Manson’s guidance. He controlled their identities, redefining loyalty, love, and morality according to his own rules. This cultivated obedience paved the way for decisions that would have once been unimaginable.

The Ideology of “Helter Skelter”

At the heart of Manson’s control was a grand, apocalyptic narrative he called “Helter Skelter.” Drawing heavily from the Beatles’ White Album, Manson convinced his followers that specific lyrics were coded messages predicting a coming race war. He interpreted songs like “Helter Skelter,” “Piggies,” and “Blackbird” as prophecies foretelling chaos between Black and white Americans. In this imagined conflict, Manson believed the Black population would rise up, overthrow white society, and eventually seek guidance from him and his followers, who would have survived by hiding in a mystical underground world.

This bizarre worldview blended racial paranoia, biblical symbolism, delusional prophecy, and countercultural rhetoric. Manson presented “Helter Skelter” as both a warning and a divine mission. The Family was no longer merely a group of drifters; they saw themselves as chosen participants in an inevitable historical upheaval. Over time, this ideology justified escalating lawlessness and violence.

Thus, the commune at Spahn Ranch evolved from a counterculture experiment into a closed, radicalised society. Under Manson’s orchestration, it became the breeding ground for one of the most notorious crime sprees in American history.

Path to Violence: Events Leading Up to the Murders

By 1969, the Manson Family had drifted far from the idealistic, free-love image they projected in their early communal days. Life at Spahn Ranch had become increasingly unstable, shaped by drug abuse, intense groupthink, and Manson’s growing paranoia. The transition from a countercultural commune to a violent criminal collective did not happen overnight—it was a slow descent propelled by desperation, delusion, and an escalating pattern of criminal behaviour.

The Family had always relied on theft and scavenging to survive, but as resources tightened, their activities expanded into more serious crimes. Members stole cars, broke into homes, and engaged in drug dealing—particularly LSD and marijuana—to maintain their lifestyle. These criminal ventures brought the group into conflict with other dealers and bikers, most notably the Straight Satans motorcycle gang. Manson’s failed drug deal with a dealer named Bernard “Lotsapoppa” Crowe in July 1969 marked a dangerous turning point. After Manson shot Crowe in a misguided attempt to resolve a dispute, he became convinced that retaliation was inevitable and that the police were closing in on the ranch. Although Crowe survived, Manson believed he had killed him, intensifying the atmosphere of paranoia and siege within the group.

These tensions fed directly into Manson’s apocalyptic preaching. He increasingly framed ordinary setbacks—drug conflicts, evictions, arrests—as signs that “Helter Skelter” was about to erupt. The Family began stockpiling weapons, rehearsing escape plans, and discussing acts of violence as both self-defence and divine mission. Loyalty was measured not by affection but by unquestioning obedience, even when the orders were extreme.

The murder of Gary Hinman in July 1969 offered the first brutal demonstration of this shift. Hinman, a music student and occasional acquaintance of the Family, became the target of Manson’s wrath after a botched belief that he possessed money to give the group. Manson sent Bobby Beausoleil, Susan Atkins, and Mary Brunner to confront Hinman, intending to pressure him into handing over supposed funds. When Hinman refused, the situation escalated into torture, with Manson himself cutting Hinman’s face before ordering his followers to kill him. They attempted to stage the scene with political graffiti in Hinman’s blood, hoping to spark racial tension and attribute the killing to Black militants.

Hinman’s death was the clearest sign that the Family had crossed a threshold. Violence was no longer hypothetical or symbolic—it had become a tool of Manson’s ideology. The murder emboldened Manson, hardened the Family’s loyalty, and set the stage for the far more horrific crimes that would soon follow.

The Tate Murders (August 8–9, 1969)

Setting the Stage

By the summer of 1969, tensions within the Manson Family had reached a breaking point. Charles Manson’s dreams of becoming a respected musician had collapsed—most painfully because of his failed relationship with producer Terry Melcher. Melcher had once shown interest in Manson’s music but ultimately distanced himself after witnessing the Family’s erratic behaviour. In Manson’s mind, Melcher represented the gatekeepers of a world that rejected him: wealth, fame, cultural influence. The home at 10050 Cielo Drive, where Melcher had once lived, became a symbolic target—an embodiment of the world that denied Manson validation.

By August, Roman Polanski and his wife, the actress Sharon Tate, were renting the Cielo Drive home. Tate, more than eight months pregnant, was living temporarily with friends: Abigail Folger, heir to the Folger coffee fortune; Wojciech Frykowski, a close friend of Polanski; and celebrity hairstylist Jay Sebring, Tate’s former lover and still a close friend. The house frequently hosted Hollywood visitors, making it a recognisable landmark in Los Angeles’ affluent Benedict Canyon.

Manson knew Melcher no longer lived there—but the house remained a symbol of betrayal, and he believed an act of violence there would ignite the chaos of “Helter Skelter.” On the evening of August 8, 1969, he ordered Charles “Tex” Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Linda Kasabian to go to the house and kill everyone inside, instructing them to make it “as gruesome as you can.”

The Night of the Crime

Shortly after midnight, the four drove up Cielo Drive. As they approached the gate, they encountered Steven Parent, an 18-year-old visiting the property’s caretaker. The parent had no involvement with the residents and was simply leaving after a brief visit. Watson stopped the car, approached Parent’s vehicle, and—despite Parent’s pleas—shot him multiple times. The parent became the first victim of the night.

The group climbed a hill, cut the telephone line, and silently made their way toward the main house. Watson, armed with a knife and a handgun, led the break-in. Kasabian remained outside as a lookout while Atkins and Krenwinkel followed Watson inside. They forced the occupants into the living room, where they tied Tate and Sebring together with a rope looped around a ceiling beam. Sebring protested Tate’s rough treatment, prompting Watson to shoot and stab him.

The Killings

The violence that followed unfolded in a frenzy of panic, terror, and brutality.

Wojciech Frykowski managed to break free from his bindings and fled toward the front lawn. Watson chased him, striking him with the gun, stabbing him repeatedly, and finally shooting him. Frykowski’s attempts to fight back made him one of the most severely injured victims.

Abigail Folger, who had also broken away, ran out onto the lawn. Krenwinkel caught up to her, stabbing her multiple times. Despite her severe injuries, Folger continued to move, prompting more stabbings until she collapsed.

Inside the house, Susan Atkins and Watson turned their attention to Sharon Tate. Tate begged them to spare her unborn child, offering herself as hostage instead. Her pleas were ignored. She was stabbed repeatedly, with Atkins participating before Watson inflicted the final fatal wounds. Of all the murders, Tate’s death became the most symbolically devastating—a rising Hollywood star, pregnant, killed in her own home.

Once the victims were dead, Atkins dipped a towel into Tate’s blood and wrote “PIG” on the front door, mimicking the political graffiti left at Gary Hinman’s murder. The message was intended to suggest a racial motive and spark societal chaos—fulfilling Manson’s delusional prophecy of “Helter Skelter.”

The killers then returned to Spahn Ranch, boasting of what they had done. Manson, upon hearing details, believed it was only the beginning of a larger plan.

Public Reaction and Media Shock

The murders sent immediate shockwaves through Hollywood and the broader Los Angeles community. News of Sharon Tate’s death—a young actress, pregnant, wealthy, living in one of the safest areas of the city—created a level of fear that transcended typical crime reporting. Rumours and speculation spread rapidly: drug deals gone wrong, ritual killings, political extremists, personal vendettas.

Celebrities began hiring private security guards. Home alarm systems, still rare at the time, were suddenly in high demand. Even ordinary families in Los Angeles reported sleeping with lights on or keeping weapons by their beds.

The press amplified every detail of the brutality, creating a sense of vulnerability that undermined the city’s glamorous image. In a broader cultural sense, the Tate murders became a symbol of the end of the 1960s, overwhelming the idealism of the decade with a chilling reminder of how radicalisation, delusion, and charismatic control could lead to unthinkable violence.

The tragedy at Cielo Drive was not only a series of murders—it was a moment that reshaped American consciousness. The sense of innocence that had marked the era was shattered, replaced by a deep uncertainty that would continue to haunt the nation long after the trials began.

The LaBianca Murders (August 10, 1969)

Why the LaBiancas Were Targeted

The murder of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, committed just one night after the carnage on Cielo Drive, reflected Manson’s shift from symbolic revenge to the deliberate creation of widespread fear. Unlike the Tate victims—who were connected to a house Manson associated with personal rejection—Leno and Rosemary LaBianca had no link to the Family. They were chosen precisely because they were random, respectable, middle-class Angelenos.

Manson wanted a murder that would feel arbitrary, unpredictable, and impossible for authorities to categorise. In his mind, killing ordinary citizens would intensify the illusion of a brewing racial uprising and further push the world toward “Helter Skelter.” After driving aimlessly through Los Angeles and its surrounding neighbourhoods, Manson selected the LaBianca home on Waverly Drive, in part because he recognised the area from previous visits and believed it offered a quiet, low-risk environment for another attack. This act marked a chilling evolution: violence was no longer personal but strategic—violence as a tool for chaos.

The Attack

Upon entering the LaBianca residence in the early hours of August 10, Manson and Tex Watson awakened Leno and Rosemary at knifepoint. Unlike the Tate murders, Manson personally initiated the assault: he tied up Leno and reassured both victims that they would not be harmed, a deliberate attempt to maintain calm before delegating the violence to his followers. Once the couple was restrained, Manson left the house, ordering Watson, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Leslie Van Houten to complete the killings.

Watson attacked Leno first, stabbing him repeatedly while Krenwinkel and Van Houten turned their attention to Rosemary, who fought violently for her life. As Rosemary struggled, the attackers stabbed her dozens of times. Watson then returned to inflict further wounds, ensuring the murders carried the same shock value and symbolic brutality as those on Cielo Drive.

Before leaving, the killers scrawled messages on the walls and refrigerator in the victims’ blood: “Rise,” “Death to Pigs,” and “Healer Skelter.” These words were intended to mimic the rhetoric of a fictitious Black uprising and to connect the murders to the same apocalyptic narrative Manson had been preaching for months.

The Start of “Helter Skelter” Panic

At first, police failed to connect the LaBianca murders to the Tate killings. The crime scenes were several miles apart, the victims had no relationship to one another, and the brutality—though similar in savagery—contained different arrangements and patterns. This initial confusion was exactly what Manson intended: a growing sense that Los Angeles was under siege by unknown forces.

The randomness of the LaBianca murders intensified public terror. The idea that anyone, in any neighbourhood, could be next created the first hints of the “Helter Skelter” panic—an anxiety that would only deepen once the crimes were later linked and their true orchestrator revealed.

Investigation, Arrests, and the Sensational Trial

Breakthroughs in the Case

In the immediate aftermath of the Tate and LaBianca murders, the Los Angeles Police Department struggled to piece together a coherent narrative. The brutality, lack of apparent motive, and seeming randomness of the victims made the crimes appear unrelated. Different police divisions handled the two cases separately, causing crucial information to remain siloed. Meanwhile, Charles Manson and his followers continued living at Spahn Ranch, confident that the killings had successfully ignited what they believed would become “Helter Skelter”—a race war they expected to lead and survive.

The first breakthrough did not come from forensics or detective work, but from a series of unrelated arrests. On August 16, 1969, a large raid on Spahn Ranch led to the detention of several Family members on suspicion of auto theft. Although the charges did not hold, these arrests put the group firmly on law enforcement’s radar. Their growing criminal portfolio—car stripping, armed robberies, intimidation of locals—made the Family a recurring nuisance for investigators.

The true turning point occurred months later, when Susan Atkins, already jailed for her role in the murder of Gary Hinman, began speaking to fellow inmates. In a startling display of loyalty mixed with bravado, Atkins boasted about her involvement in both the Tate and LaBianca killings. She claimed she had stabbed Sharon Tate and smeared the word “PIG” on the door in Tate’s blood. Her cellmate alerted authorities, leading detectives to re-examine the link between the two crime scenes. Atkins’ confession finally connected the dots: the handwriting, the brutality, the symbolic messages, and the overlapping cast of suspects pointed unmistakably toward the Manson Family.

Investigators began revisiting earlier interviews, cross-checking timelines, and assembling an emerging picture of a cult-like group driven by an unstable leader’s apocalyptic fantasies. By late 1969, arrest warrants for Manson, Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie Van Houten, and Charles “Tex” Watson were issued, marking the beginning of one of the most sensational criminal proceedings in American history.

The Trial of the Century (1970–71)

The Tate-LaBianca trial opened in June 1970 and almost immediately transformed into a cultural and media spectacle. The prosecution chose to combine charges for both sets of murders, arguing successfully that they formed a unified pattern orchestrated by a single mastermind—Charles Manson. This approach allowed them to present the Family’s ideology and the Helter Skelter motive cohesively, giving the jury a narrative structure for acts that otherwise defied rational explanation.

A key figure in the prosecution’s success was Linda Kasabian, who received immunity in exchange for testimony. As a member of both murder squads, she witnessed much of the violence firsthand but did not commit any killings. Her calm, detailed description of the events provided the jury with a chilling window into the Family’s internal world. Kasabian’s credibility was strengthened by her emotional reactions and her clear fear of Manson, making her the prosecution’s star witness.

The courtroom itself often descended into chaos. Manson carved an “X” into his forehead, later altering it into a swastika. His followers, including the female co-defendants, mimicked his self-mutilation, shaved their heads, and chanted outside the courthouse. They sang, performed ritual-like gestures, and attempted to intimidate witnesses. At one point, Manson lunged at the judge, forcing bailiffs to restrain him. These antics reinforced the prosecution’s portrayal of Manson as a manipulative cult leader capable of controlling every aspect of his followers’ behaviour.

The combination of bizarre courtroom behaviour, the celebrities involved in the case, and the shocking nature of the crimes ensured constant media attention. Newspapers, radio, and television framed the trial as a symbol of the dark side of the counterculture era—where the promise of peace, music, and free expression collided with violence and delusion.

Verdict and Sentencing

On January 25, 1971, the jury convicted Charles Manson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Tex Watson of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Leslie Van Houten, present only at the LaBianca crime scene, was convicted separately in her own trial. All were originally sentenced to death.

However, in 1972, the California Supreme Court abolished the death penalty, automatically commuting all existing death sentences to life imprisonment. For the Manson defendants, this meant decades of parole hearings, psychological evaluations, and ongoing public outrage. Susan Atkins, critically ill in her final years, was repeatedly denied compassionate release. Charles Manson remained a symbol of criminal infamy until his death in 2017. Krenwinkel, Van Houten, and Watson continued to face the parole board, with Van Houten eventually receiving parole in 2023 after more than fifty years behind bars.

These long arcs of imprisonment illustrate both the enduring horror of the crimes and society’s continued struggle to reconcile justice, rehabilitation, and the legacy of one of America’s darkest criminal chapters.

Psychological and Sociological Analysis

Cult Indoctrination and Vulnerability

To understand how Charles Manson built a following capable of committing extreme violence, it is necessary to situate the Manson Family within the broader social landscape of the late 1960s. This was a period defined by generational rebellion, disillusionment with authority, and widespread experimentation with alternative lifestyles. Many young people were searching for belonging, spiritual meaning, and emotional refuge during a time marked by the Vietnam War, the civil rights struggle, and shifting cultural norms. Against this backdrop, the Manson Family emerged as one of many communes promising freedom, unity, and escape from mainstream society.

The individuals who joined Manson were often young, idealistic, and emotionally unmoored—runaways, recent dropouts, or those estranged from their families. They were not seeking violence; rather, they sought connection, acceptance, and a sense of purpose. Manson offered these things through charismatic storytelling, nonjudgmental affection in the early stages, and the allure of a utopian community. Their vulnerabilities—psychological, economic, and social—made them particularly susceptible to manipulation. What began as a seemingly harmless communal experiment gradually evolved into a coercive micro-society dominated entirely by Manson’s will.

Manson’s Manipulation Techniques

Manson’s leadership relied on a calculated blend of psychological conditioning and social control. He used LSD and other psychedelics not as tools for enlightenment, but as instruments for breaking down personal boundaries. During these drug-fueled sessions, he positioned himself as a messianic interpreter of their visions, reinforcing his authority. Over time, he severed Family members’ ties to the outside world—discouraging contact with families, stripping them of possessions, and moving them into increasingly isolated environments such as Spahn Ranch and the desert. Isolation was essential: without external reference points, Manson’s worldview became the only reality.

He also employed classic cult techniques: alternating affection with humiliation, dismantling previous identities, and redefining moral boundaries. Members were encouraged to abandon individual thought, surrendering decision-making to Manson, who framed himself as both protector and prophet. Through repetition of apocalyptic narratives, he transformed ordinary anxieties into a shared belief in an impending racial war. Once this worldview was deeply internalised, violence became not only justified but necessary—an act of devotion to the leader and the imagined future he promised.

Manson’s true power lay in his ability to convert vulnerable individuals into agents of his own delusion, demonstrating how charismatic authority, psychological manipulation, and social instability can converge with catastrophic consequences.

The End of the Sixties: Cultural Fallout and Legacy

Collapse of the Counterculture Dream

The Tate-LaBianca murders became a symbolic rupture in American cultural history—an event so shocking and senseless that it effectively marked the death of the 1960s counterculture dream. For years, the hippie movement had championed peace, communal living, and the transformative power of love. Yet here was a commune, led by a self-styled guru, producing not enlightenment but brutal, ritualistic violence. The contradiction was impossible to ignore. Suddenly, the utopian promises of the decade appeared dangerously naïve.

The murders shattered the public’s ability to romanticise the counterculture. Communes were no longer viewed as harmless experiments in alternative living; they became potential breeding grounds for radicalisation and instability. Parents grew fearful of their children’s involvement in the hippie scene. What had once felt like liberation now seemed like chaos, and the nation, already weary from protests, assassinations, and political turmoil, interpreted the Manson crimes as the final, horrifying unravelling of the decade’s idealism.

In many ways, the Manson case closed the curtain on the 1960s. It exposed the darker currents beneath the era’s optimism—the vulnerability of disaffected youth, the destructive potential of charismatic leaders, and the fragility of movements rooted in spontaneity rather than structure.

Media Representations and Myth-Making

From the moment news broke, the Manson murders became a media obsession. Their combination of celebrity, counterculture, and unimaginable brutality made the story irresistible to the public and press alike. Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter (1974) became one of the best-selling true crime books of all time, solidifying the prosecution’s narrative in popular memory. Numerous documentaries, television specials, and dramatisations soon followed, each shaping the case into a modern American myth.

The story’s persistence in popular culture—appearing in works like Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (2019)—reflects more than fascination with violence. It taps into anxieties about lost innocence, manipulation, and how easily idealistic movements can fracture into extremism. Over decades, Manson himself morphed into a pop culture archetype: the dangerous guru, the manipulative cult leader, the embodiment of the era’s collapse. Media representations did not simply recount the crimes—they transformed them into symbols, cautionary tales, and cultural touchstones.

Long-Term Effects on Criminal Justice and Society

The Manson case also had profound implications for criminal justice and public consciousness. It led to greater scrutiny of cults, spiritual movements, and fringe communities, influencing how law enforcement approached groups that exhibited signs of coercion or charismatic control. The murders reinforced the idea that ordinary individuals could be conditioned into committing extreme acts—reshaping discussions around brainwashing, collective psychology, and legal accountability.

On a societal level, the random and seemingly motiveless nature of the violence instilled a long-lasting fear. The victims had no connection to their killers; they represented a terrifying truth: violence could strike anyone, anywhere, without warning. This fear lingered into the 1970s, a decade marked by rising crime rates and declining trust in institutions.

The legacy of the Manson murders is thus twofold: a cultural wound that marked the end of an era, and an enduring symbol of how fragile social optimism can be in the face of manipulation, delusion, and violence.

Conclusion: The Continuing Fascination with the Manson Case

More than half a century after the Tate-LaBianca murders, the Manson case continues to haunt the American imagination. Its enduring grip comes not only from the shocking brutality of the crimes, but from what they revealed—about the fragility of social movements, the dangers of manipulation, and the dark edges of a culture in transition. Manson and his followers emerged at the intersection of celebrity, counterculture, and generational upheaval, producing a story that still defies easy explanation. It is this complexity that keeps the case alive in public memory.

The fascination also lies in its warnings. The Manson Family demonstrates how ordinary individuals can be drawn into destructive belief systems when they feel unmoored, alienated, or hungry for belonging. It shows how a charismatic figure can exploit personal vulnerability, bending idealism into obedience and turning spiritual searching into violence. In studying the case, psychologists, criminologists, and historians continue to uncover insights into radicalisation, groupthink, and the mechanics of cult control—lessons that remain urgently relevant in a world still grappling with manipulation, misinformation, and extremist movements.

The case also reflects the tensions within celebrity culture. Sharon Tate’s murder symbolised the shattering of Hollywood’s mythic glamour, reminding the world that fame offered no protection against chaos. The media frenzy that followed revealed how tragedy can be magnified, dramatised, and mythologised until it becomes woven into a nation’s cultural fabric.

Ultimately, the Manson story persists because it is more than a crime; it is a parable about a generation’s search for meaning and the catastrophic consequences when that search is hijacked by someone skilled in exploiting fear, hope, and vulnerability. As long as societies wrestle with questions of identity, belonging, and belief, the events of 1969 will continue to resonate—both as a cautionary tale and a stark reminder of how easily darkness can take root under the guise of enlightenment.

Reference Sources

- Manson Family (cult & criminal organization)

- Charles Manson – Tate-LaBianca Murders

- Tate Murders (Event page)

- Trial, motive, and conviction

- Spahn Ranch and the Manson Family

- Tate–LaBianca Murders

- Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders — Vincent Bugliosi & Curt Gentry (One of the most authoritative sources; available on Amazon/Google Books)