While engaging in the research of the publication Hans, I did not simply conduct a study on a product; I witnessed a cultural institution that has fought off death and continues to survive today, for 94 years. By any reasonable modern business rule, Hans should have failed several years ago, yet it continues to exist today by the will of the people involved in the magazine.

Many years ago, all regional magazines in India sold a range between 15,000-100,000 copies per issue, whereas today Hans (which has long been considered the last major pillar of Hindi literary publishing) sells around 12,000-13,000 copies a month at best(the majority being vendor refunds).

Due to COVID-19, Hans had little to no choice but to go online, and the process was difficult; not only has the audience (the number of readers) decreased dramatically, but many past patrons did not know how to read online and could not adapt.

One notable incident occurred after the passing of the magazine's editor, Rajendra Yadav, in 2013. The entire staff voluntarily cut their own salaries just to ensure the survival of the publication, which speaks to the commitment of the staff to the magazine.

1. INTRODUCTION

Why This Matters (And Why I Chose This Topic)

To be candid, I had assumed that my path of research into language-specific regional literary publications would yield an ordinary tale of how traditional publishing has suffered from digital disruption; namely, that print media such as newspapers/magazines will likely continue downward spirals in an age where digital services dominate access to content; however, Hans magazine made me dig much deeper.

The central question of this case study is deceptively simple: Will subscription services—whether they are offered in a printed format, digital-only model or a combination of both help save regional literary publications? Or, would we be witnessing a slow-motion demise of these cultural institutions?

I concentrated my analysis on Hans magazine, but I added similar issues related to published works within the Bengali and Marathi languages to determine whether or not any trends existed simultaneously between those groups as well; and, spoiler alert—they did—with the situation being much worse than I originally anticipated.

What We're Actually Talking About

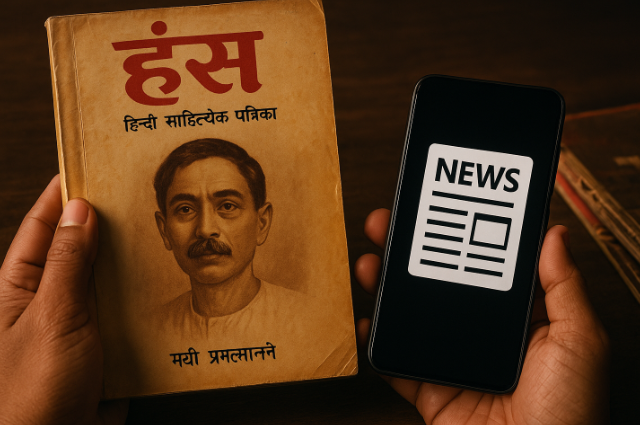

Founded by Munshi Premchand in 1930, Hans was a literary magazine with a mission statement to unite India to resist British colonialism. Mahatma Gandhi was an editorial board member.

Currently, I am looking at Desh, a Bengali magazine that began in 1933 and Vangmayshobha, a Marathi magazine that existed between 1939 and 1992, as their goal was not about making money but serving as a platform for writers, including controversial ones, to have their work published. These are what scholars have termed "sites of literary activism or literary upliftment" for all

those writers who may not have had the opportunity to publish their works otherwise, and for many reasons: to keep regional languages alive, and to provide literary support to unknown writers, as well as writers from a minority background.

Why You Should Care

What happens when these magazines shut down? How do Hindi and Marathi aspiring writers publish their work? What's happening there is that regional language publishers are becoming smaller and less diverse and will be losing their prestige/value. By losing these publishers, marginalised communities such as Dalit authors, feminist writers, and young people from resettlement areas will lose the only vehicles for their writing to actually be published. You may be thinking to yourself, "Can't these writers just publish their work online?" That's what this case study examines.

The Central Question

Can market forces (subscriptions, advertising, reader willingness to pay) allow for the sustainability of quality regional literary magazines, or do cultural institutions have to rely on other means of support, such as subsidies, grants and institutional support? I began this research with high hopes and ended it without any hope.

2. BACKGROUND

The Golden Age Nobody Talks About Anymore

Regional literary publications in India were dominant cultural entities from the 1950s through the 1980s. They were much more than somewhat influential in the scope of academia, but were instead responsible for moulding actual literary movements by introducing new authors into the canon.

The variety of Hindi magazines during this time ranged from very small literary imprints to large illustrated weekly magazines. The circulation figures for these magazines were between 15K – 100K per issue, which is quite large when compared with the published sales of books. In terms of readership and author recognition, writers of poetry and creative fiction used published magazines as the primary means of achieving recognition and attaining readers for their works.

The Marathi Little Magazine Movement began around 1960 as writers expressed their discontent with the bourgeois literary establishments. Bengali magazines such as Krittibas (est. 1953) published many of the experimental poets who are currently taught at universities. These magazines also translated Tolstoy and Chekhov into regional languages for regional readership, published cross-linguistic dialogue, and provided a venue for whole literary movements.

Another aspect that I found interesting is that the magazines created reading communities in reality. People would pass copies to each other in their families and communities. There would be conversations about the most current issues, and people would discuss and debate the various essays and stories. There is no longer any significant aspect of this shared cultural production through reading and discussion.

Hans: A Magazine That Wouldn't Stay Dead

An interesting story of Hans is about the personal inclination of the founders. Munshi Premchand, who is also known as Upanyas Samart (king of novels), founded Hans in 1930 with the support and help of Mahatma Gandhi as one of its advisors on the Editorial Board. One of the statements mentioned by Premchand and Gandhi was that Hans would inspire people in India to unite and rise up and fight against British Imperialism.

The British Colonial Government was not very happy about that. As a result of the immediate pressure of Politics and Finance, it was very difficult for Hans to survive after the Death of Munshi Premchand in 1936, and when his son Amrit Rai tried to keep it alive, he finally stopped trying in 1956. After that, for a period of 30 years, Hans did not exist.

In 1986, Rajendra Yadav, who is a well-known short story writer, started Hans again as a Mission. Under his editorial direction, which was for 27 years, Hans became the leading Hindi Literature Journal and created a space for Feminist and Dalit writers. Rajendra created a column called Ghuspaithiye, which means "Intruders." That column included stories by writers who were under 20 years old and who came from the lower sections of society, like students who lived in resettlement colonies and were raised with struggles, rather than with books.

Rajendra Yadav is credited with bringing authors like Uday Prakash, Mridula Garg, and Ajay Navaria to prominence. These authors are now well-known and admired in the field of Hindi Literature. Hans was responsible for discovering them.

The Comparison Cases (And Why They Matter)

Desh: The Bengali publication dubbed The New Yorker of Bengal launched in 1933. Nearly every major Bengali writer got published there—Rabindranath Tagore, Satyajit Ray, the whole pantheon. But after editor Sagarmoy Ghosh died in 1997, something shifted. The magazine moved away from purely literary content toward current affairs essays and general-interest pieces.

Why? Survival. Desh had one major advantage Hans lacked—it was owned by Anandabazar Patrika Limited, one of Bengal's largest newspaper groups. Institutional backing kept it alive, but at the cost of its original literary mission. That's a trade-off worth examining.

Vangmayshobha: The Marathi tragedy. N.G. Kelkar edited this magazine for 53 years (1939-1992), enriching Marathi literature with work from G.A. Kulkarni, Vinda Karandikar, and others. He treated it as what he called a laboratory to create literature, not a profit centre.

When television and movies started competing for attention in the 1980s-90s, Kelkar fought hard. But survival proved impossible. After he died in 1994, his family published one final obituary issue and closed Vangmayshobha permanently. No amount of passion or commitment could overcome the economic realities.

That closure haunts this entire case study. Because if dedication and literary vision weren't enough, then why would they be enough now?

How We Got Here (The Decline in Numbers)

The contemporary landscape is honestly pretty stark. Average Issue Readership numbers have just collapsed across the entire magazine industry. India Today - which is the highest-read English magazine in the country - saw an 8.7% readership decline. Business magazines dropped anywhere from 7-24%. For small literary magazines without commercial advertising or institutional backing? The decline has been absolutely catastrophic.

Here's the economic breakdown that basically killed the traditional model:

Print advertising historically provided 73% of magazine revenue. Circulation - so subscriptions plus newsstand sales - provided just 27%. Now digital advertising captures over 50% of total advertiser spending, and print ad budgets are contracting year over year.

Meanwhile, distribution networks are literally collapsing. Those hawkers and book agents who used to sell magazines at railway stations and newsstands? They've abandoned the business. It's not profitable anymore. And younger demographics have fundamentally shifted toward screens and instant gratification. The slow, contemplative reading that literary magazines require seems increasingly like some antiquated luxury that nobody has time for.

3. PROBLEM STATEMENT

Let me just be as blunt as possible here. Regional literary magazines are facing three interconnected challenges that are strangling them simultaneously.

Economic Collapse

That 73% advertising and 27% circulation revenue model I just mentioned? Completely unsustainable now. And literary magazines always attracted minimal advertising even during print's dominance. Luxury brands, financial services, consumer products - the high-margin advertisers who actually have money to spend - they see zero value in literary audiences. They view them as small and uncommercial.

Hans costs 50 rupees per issue. The editors have explained that for some readers, even these prices are only barely affordable. That's a philosophical commitment to accessibility, right? But it's also economic suicide.

Think about it: 600 rupees annually from 12,000 subscribers generates just 7.2 million rupees. That's not enough to pay even a small editorial team, forget about compensating writers decently.

Cultural Displacement

Free digital content has fundamentally changed what people expect from media. Why pay for a literary magazine when infinite content exists for free? YouTube, social media, blogs, news sites - they're all competing for the same attention. And they're optimised for engagement through algorithms, not editorial judgment about literary quality.

The slow, sustained reading these magazines require? It increasingly seems like something from another era. Reading communities that used to form around shared magazine experiences are fragmenting into digital atomization. People used to gather and discuss the latest issues, pass copies around neighbourhoods, and debate essays and stories together. That's mostly gone now.

Infrastructure Decay

Physical distribution networks are collapsing because vendors literally can't make money selling magazines anymore. The economics don't work for them. Digital infrastructure requires technical expertise and investment that small literary operations just don't have. The transition from print to digital demands not just format conversion but complete operational transformation - and most magazines lack the resources for that kind of overhaul.

So Here's the Core Question

Can market-based subscription models generate enough revenue to sustain quality regional literary magazines? Or do these cultural institutions need non-market subsidy mechanisms to survive?

And here's why this matters beyond just magazine survival: When these publications die, linguistic homogenization accelerates. English becomes the default language of serious literary discourse. Regional languages lose prestige and complexity.

Aspiring writers in Hindi, Marathi, and Bengali face this awful choice - switch to English where there's still some publishing infrastructure, or accept that serious literary careers in their mother tongue aren't viable anymore. That's devastating for cultural diversity.

Marginalised voices lose platforms. Magazines like Hans deliberately focused on Dalit writers, feminist voices, and young writers from society's margins - voices that commercial publishing would never platform. When magazines go under, where do those voices go? Nowhere, really.

4. METHODOLOGY

The Approach

This used qualitative methodology combining documentary analysis, comparative case examination, and economic evaluation. Hans served as the primary case, but Desh and Vangmayshobha were brought in to see if patterns held across different regional languages and contexts.

Where the Data Came From

Primary Sources:

Editorial statements from Hans editors over the years - Rajendra Yadav, Sanjay Sahay, Rachana Yadav. Published circulation data, subscription figures, and digital transition reports from the 2020-2024 pandemic period. Magazine pricing information and whatever revenue model documentation was publicly available.

Secondary Sources:

Industry reports on readership decline and advertising trends. Academic literature on literary magazine history is actually a surprisingly robust field. News coverage of regional publishing challenges. Digital platform analytics from services like Magzter.

Comparative Analysis:

Cross-magazine circulation trend comparisons, revenue model analysis across Hindi, Bengali, and Marathi publications, digital transition strategy comparisons and their outcomes.

The Analytical Framework

Three main lenses for evaluation:

- Economic Viability: Can subscription revenue actually sustain operations given fixed costs and market constraints? Looking at pricing, circulation numbers, production costs, and advertising revenue, the full financial picture.

- Cultural Impact: What functions do these magazines serve in linguistic preservation, writer development, community building, and platforming marginalised voices? This is harder to quantify but arguably more important than the economics.

- Strategic Adaptation: What specific strategies have magazines employed to navigate digital disruption? Which ones worked, which failed, and why?

Limitations - Being Honest About Constraints

Access to detailed financial records from privately operated magazines was limited. Most publications don't publish comprehensive financial data, understandably.

Quantifying cultural impact is inherently difficult - how do you actually measure the value of linguistic diversity or marginalised voice platforming? You can't really put a number on that.

The recency of digital transitions limits longitudinal assessment. We just don't have enough time-series data yet to see long-term patterns. And separating pandemic-specific disruptions from longer-term structural trends proved challenging. COVID-19 accelerated existing problems but also created unique circumstances that might not represent the normal trajectory.

5. FINDINGS AND PRESENTATION

Hans Magazine - The Current Reality

The Numbers (And What They Actually Mean)

Hans maintains about 12,000-13,000 monthly readers. That breaks down to 2,500 annual subscribers plus 9,000-11,000 copies sold through vendors. But editor Sanjay Sahay made this interesting point that kept coming up - the actual readership is likely much higher. Way higher.

In 2019, Sahay explained that Yadav believed that for every house that it goes to, at least ten people read it. If that's true, you're looking at over 100,000 total readers. Copies circulate among families, get passed around neighbourhoods, and are discussed in reading groups. One copy has this ripple effect.

This makes Hans the largest-read Hindi literary magazine, even as circulation sits dramatically below the historical 15,000-100,000 range that magazines commanded during their golden age.

Pricing Philosophy (Or: How to Go Broke With Dignity)

50 rupees per issue. 600 rupees annually. This isn't market-optimised pricing - it's a philosophical statement. The magazine deliberately keeps prices low because, as editors bluntly stated, for some readers, even these prices are only barely affordable.

This prioritises accessibility over profitability. It aligns with the magazine's mission to serve a broad readership rather than an elite minority. But financially? It's completely unsustainable.

The Financial Crisis Nobody Talks About Publicly

When Rajendra Yadav died in 2013, the magazine faced its severest test. Here's what happened next, and it's the part that really drives home that this isn't just a business story - the editorial staff collectively decided to cut their own salaries to keep publication alive.

Sahay's statement still echoes: "We are not here to earn salaries, we are rather on a mission to ensure that this historical literary magazine stays afloat and the flag of Hindi literature keeps flying high."

The magazine operates in a sustained deficit. It survives not on sound business economics but on the dedication of underpaid staff willing to subsidise the publication through foregone wages. That's not a sustainable model - it's martyrdom.

Leadership Transition (And Unexpected Inheritance)

Yadav's daughter Rachana inherited management. She's a Kathak dancer with no literary background. The literary community definitely had opinions about this.

She acknowledged it frankly: "People thought there were many better people who deserved it. I was seen as a dance, advertising girl who came in one day and took over."

Over six years, she's navigated the magazine through its most challenging period - the pandemic digital transition. That takes a particular kind of stubbornness and commitment.

The Pandemic Pivot (When Everything Accelerated)

Crisis Response

COVID-19 forced the issue. As a magazine that holds a record for not missing a single issue since its revival, Hans faced an impossible situation in April 2020 - print distribution became literally impossible. Physically couldn't happen.

So they went digital. Not as a carefully planned strategic choice, but as an emergency response. Do or die situation.

What Actually Happened (The Sobering Results)

The editors' assessment: "Our readership dropped drastically. Our readers just couldn't make the transition to online reading."

First-month downloads were minimal. Numbers gradually increased but never matched print sales levels. And here's the real kicker - advertisers wouldn't pay for digital editions at print rates. Why would they? Digital advertising is fundamentally cheaper and more targeted. The revenue shortfall was severe.

The Hybrid Model They Built

Hans developed this multi-pronged strategy to survive:

- Dual Format Distribution: Keep both print and digital alive simultaneously. Print serves the core older readership that refuses to transition or simply can't. Digital serves younger, geographically dispersed readers and the global diaspora who want access but can't get physical copies easily.

- Digital Platform Partnerships: Made the magazine available through platforms like Magzter. This outsourced the technical infrastructure of digital delivery while expanding distribution reach. Let someone else handle the tech side.

- Archive Monetisation: This was actually pretty clever - they recognised that 94 years of content represents valuable intellectual property. Organised thematic anthologies from the archives: best stories by women, stories by writers from overseas. Created new revenue streams from existing content that was just sitting there.

- Social Media Engagement: Heightened social media activities during the pandemic generated overwhelmingly positive responses. Built community and awareness even when print distribution was disrupted. People couldn't get physical copies, but could still engage with the magazine's presence online.

- Website Direct Sales: Started offering PDF downloads directly through their website. This captures revenue that would otherwise go to intermediaries and platform fees.

The Problems That Won't Go Away

But here's the reality: Digital subscriptions haven't replaced lost print advertising revenue. Not even close. The magazine still operates in a sustained deficit.

Younger readers preferring digital can't compensate for older readers' print spending because digital subscription prices have to be lower, and advertising rates are depressed. You can't charge the same for a PDF as for a physical magazine, and digital ads pay way less than print ads used to.

Traditional vendors who sold Hans at railway stations and newsstands have largely abandoned magazine distribution. The business doesn't work for them anymore. This means physical copies are harder to obtain, even for readers who actively want them. You want to buy it, but literally can't find it for sale.

And in an attention economy dominated by viral content and algorithmic feeds, the contemplative reading that literary magazines require is increasingly perceived as a luxury rather than a necessity. People's brains are being rewired for quick hits of content, not sustained deep reading.

What Happened to the Others

- Desh

Unlike independent Hans, Desh survives through ownership by a major newspaper group. Institutional support makes financial survival possible. Big difference when you've got a parent company with deep pockets backing you up.

But even with that backing, Desh compromised its original literary focus. Transitioned toward current affairs and general-interest content. This is survival achieved through mission dilution - staying alive by becoming something different from what you started as.

- Vangmayshobha

This case reveals the harshest truth encountered in this whole study. For magazines dependent on singular visionary editors without institutional backing, no digital transformation strategy offers salvation. When resources are insufficient, passion alone can't sustain publication.

Vangmayshobha's closure demonstrates that hybrid models and digital subscriptions can't resurrect publications once the driving editorial force and financial capacity are exhausted. The magazine is gone. Done. Its 55-year archive has been digitised - basically a memorial to what was lost.

6. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

The Economics of Impossibility

How the Revenue Model Collapsed

Traditional magazine economics relied on 73% advertising and 27% circulation. This worked when print advertising was advertisers' primary option. Makes total sense, right? Advertisers had limited choices, and magazines captured that spending.

Today? Digital advertising exceeds 50% of the total market and keeps growing. Print advertising budgets contract year over year. For literary magazines specifically, the situation is even worse than for general publications.

Unlike news or lifestyle magazines, literary publications attract minimal advertising. Think about it - luxury goods, financial services, consumer products (the high-margin advertisers with actual money) see little value in literary audiences. They perceive them as small and uncommercial. From a purely business perspective, they're not wrong.

Why Costs Won't Budge

Costs remain stubbornly fixed regardless of format:

- Editorial costs: Quality literature requires skilled editors, which demands fair compensation. You can't just hire anyone off the street.

- Production costs: Printing, paper, and binding - all rising with inflation. These physical costs just keep going up.

- Physical distribution: Expensive and inefficient for small runs. When you're only printing 12,000 copies, the per-unit cost is high.

- Author payments: Reputable magazines must pay writers, even if modestly. You can't just ask for free content and expect quality work.

Going digital eliminates printing and physical distribution costs. But editorial costs remain identical. A magazine publishing 100 pages monthly needs the same editorial work whether it's print or digital. Someone still has to read submissions, edit pieces, layout the magazine, and manage contributors.

So digital reduces costs by maybe 30-40%. But if advertising revenue drops 70%? The math just doesn't work out.

The Pricing Paradox Nobody Can Solve

Literary magazines face this cruel dilemma. Their natural audience - serious readers, often students, teachers, middle-class intellectuals - has limited disposable income. Pricing at 600 rupees annually (50 rupees per issue) is considered barely affordable by Hans's own editors.

But let's actually do the math: 600 rupees annually from 12,000 subscribers generates 7.2 million rupees in revenue. That's insufficient to pay even a small editorial team, let alone compensate writers decently.

International literary magazines charge 3,000 to 10,000 rupees annually because their audiences have higher purchasing power. Indian regional magazines lack that option. Their readers simply can't afford those prices.

Raise prices? You shrink the already small subscriber base. Keep prices low? You ensure accessibility but guarantee financial unsustainability.

This dilemma has no economic solution - only philosophical choices about who bears the subsidy burden.

What Dies When Magazines Die

Linguistic Diversity

Regional literary magazines are vehicles of linguistic preservation and evolution. When Hindi or Marathi magazines publish experimental fiction, they expand the expressive possibilities of those languages. They push boundaries, try new forms, and experiment with style.

When they translate world literature, they enrich the vocabulary and conceptual frameworks available to writers. They bring in ideas and techniques from other traditions.

Magazine death accelerates linguistic homogenization. English becomes the default language of serious literary discourse. Regional languages, increasingly confi ned to domestic and informal spheres, lose prestige and complexity. They become languages you speak at home but not languages you use for sophisticated intellectual work.

Literary Pathways Close

For aspiring writers in regional languages, magazines historically provided the primary pathway to publication and recognition. Book publishers rarely take risks on unknown writers - their margins are too tight. But magazines can and do take those chances.

The little magazine movement in Marathi, Bengali, and Hindi created the infrastructure through which generations of now-canonical writers emerged. These magazines discovered and nurtured talent that later became major literary figures.

As magazines disappear, aspiring regional-language writers face this awful choice: switch to English to access remaining publication opportunities, or accept that serious literary careers in their mother tongue aren't viable anymore. That's a devastating choice to force on someone.

Reading Communities Fragment

Hans editors believe their 12,000 subscribers represent over 100,000 actual readers because copies circulate among families and friends. These magazines create communities bound by shared reading experiences - people who discuss the latest issue, debate stories and essays, and collectively construct meaning together.

Digital platforms promise connection but deliver atomization. Online reading is fundamentally solitary. You're alone with your screen. Comments sections create the illusion of community while actually fostering hostility and superficial engagement. It's not the same as gathering with people to discuss what you've all read.

The loss of print magazines means the loss of these reading communities and the shared cultural literacy they sustained.

Marginalised Voices Get Erased

Publications like Hans, with its deliberate focus on Dalit, feminist, and outsider writers, created rare platforms for voices excluded from mainstream publishing. These magazines could afford to publish uncommercial but culturally vital perspectives because they operated under different value systems than purely commercial enterprises. They weren't just chasing profit.

Digital platforms governed by algorithms optimised for engagement and advertising revenue systematically deprioritise challenging content. The economic imperative overwhelms editorial independence. Algorithms don't care about giving voice to marginalised communities - they care about clicks and engagement metrics.

Where do marginalised voices go when these platforms disappear? Nowhere, mostly. They just get silenced.

Can Subscription Models Actually Work?

What Happened Internationally

Globally, the transition to digital subscriptions succeeded primarily for news publications with strong brand recognition and resources to invest heavily in digital infrastructure: The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post.

But even these success stories required massive initial investment and years of losses before achieving sustainability. And these are major international news organisations with huge resources, not small literary magazines scraping by.

Literary magazines, even in wealthy markets, struggle profoundly. In the United States, most serious literary magazines survive through university subsidies, foundation grants, or wealthy individual patrons. Subscription revenue alone can't sustain them, even in America, where people have way more disposable income.

In India? These support systems barely exist. Universities lack resources for magazine subsidies. Foundations funding literary endeavours are rare. Individual patronage of the arts remains uncommon. The infrastructure just isn't there.

The Hybrid Model's Fatal Flaws

Hans's experience reveals five fundamental limitations of hybrid print-digital subscription models:

One:

Digital subscriptions at necessarily low prices can't replace lost advertising revenue. The math simply doesn't work. You'd need tens of thousands more subscribers to make up that gap.

Two:

Print readers and digital readers want different things. Serving both well requires duplicate effort and expense. You're essentially running two different publication operations simultaneously.

Three:

Distribution networks collapse. As fewer people buy print, the infrastructure supporting print distribution falls apart. Vendors quit, newsstand space disappears. This makes print copies harder to obtain, even for willing customers. It creates this death spiral where availability decreases, which decreases sales, which decreases availability further.

Four:

Generational turnover works against you. Older readers who prefer print and can afford subscriptions are ageing out. They're literally dying. Younger readers prefer digital but have less willingness to pay for content - they've grown up in an internet era where everything is free. This gap can't be bridged through pricing strategy alone.

Five:

Digital subscriptions compete with infinite free content. Not just other magazines - social media, YouTube, blogs, free news sites, everything. The attention economy is absolutely brutal for paid literary content. Why pay when free content is everywhere?

7. RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLEMENTATION

What Magazines Can Do (Survival Strategies)

- Go Digital-First (But Keep Print as Premium): Embrace digital as the primary format, but maintain print as a premium offering for devoted subscribers willing to pay higher prices. This flips the current model but acknowledges reality. Most people will consume digitally, but hardcore fans will pay extra for physical copies.

- Monetise Your Archives: Hans showed that this actually works. Ninety-four years of content represent valuable intellectual property. Organise thematic anthologies, create searchable databases, and develop educational partnerships around historical content. That content is just sitting there - make it work for you.

- Build Actual Communities: Not just social media presence - actually invest in online events, virtual literary festivals, and reading groups. Create engaged communities that value the magazine's mission beyond just consuming content. Give people reasons to feel connected to the magazine and each other.

- Collaborate with Others: Form consortia of regional literary magazines to share digital infrastructure costs. No single small magazine can afford a robust digital infrastructure, but five magazines splitting costs? Maybe that works. Pool resources where it makes sense.

- Partner with Educational Institutions: Integrate magazine content into school and university curricula. Create institutional demand beyond individual subscriptions. If literature students are assigned to read Hans for class, that's guaranteed readership and potential subscription revenue.

What Policymakers Should Do - If They Care

Create Cultural Subsidy Programs

Establish government grants for literary magazines meeting quality and inclusivity criteria. Critical point - use arm's-length administration to prevent political interference. You don't want the government directly controlling content. The Sahitya Akademi could potentially administer such programs independently.

- Offer Tax Incentives: Provide tax benefits to corporations and individuals supporting literary publications. Make cultural patronage financially attractive. If companies get tax breaks for funding magazines, more of them will do it.

- Fund Shared Digital Infrastructure: Create shared digital platforms allowing multiple regional magazines to publish with minimal technical overhead. This reduces the barrier to digital transition. Let magazines focus on content while the platform handles tech.

- Subsidize Distribution: Support the distribution of literary magazines to libraries, schools, and cultural centres. Ensure accessibility even when commercial distribution fails. Get magazines into public institutions where people can access them for free.

What Readers and Writers Can Do - Yes, You

- Treat Subscriptions as Cultural Acts: Recognise that subscribing to regional literary magazines isn't really a purchase - it's cultural preservation. You're subsidising infrastructure that markets won't support, but society needs. It's almost like a donation to a cause you believe in.

- Organise Community Subscriptions: Form reading groups, share subscriptions, and maximise the value and impact of each subscription. Recreate those reading communities that used to form naturally. Get five friends together, split one subscription, and discuss what you read together.

- Advocate Loudly: Articulate why these magazines matter. Push back against the narrative that print literary culture is obsolete or that everything should be decided by market forces. Make noise about it. These magazines need vocal supporters.

Implementation Timeline - Being Realistic

Short-term (0-12 months)

- Magazines: Launch crowdfunding campaigns, strengthen social media presence, and start conversations with potential partners. Build awareness and momentum.

- Policymakers: Conduct feasibility studies for subsidy programs and examine international models. Figure out what's actually workable.

- Readers: Form advocacy groups, increase subscription rates, and organise community initiatives. Start building grassroots support.

Medium-term (1-3 years)

- Magazines: Develop digital archives, establish academic partnerships, and experiment with new revenue models. Try different approaches and see what sticks.

- Policymakers: Implement pilot subsidy programs, create tax incentive structures, and evaluate outcomes. Test things on a small scale first.

- Readers: Establish sustained reading communities, organise literary events, and build infrastructure. Create lasting structures that can sustain engagement.

Long-term (3-5 years)

- Magazines: Achieve sustainable hybrid operations with diversified revenue streams. Multiple income sources, so you're not dependent on any single one.

- Policymakers: Scale successful subsidy programs nationally, adjust based on outcomes. Take what worked in pilots and expand it.

- Readers: Build an intergenerational reading culture valuing regional languages and literary production. Create cultural shifts that make this sustainable long-term.

So can subscription models save print culture?

That question kind of assumes economics is the relevant framework here. Maybe it's not.

Hans has survived 94 years not through sound business models but through commitment - Premchand's anti-colonial vision, Yadav's social justice mission, Rachana's inherited sense of duty, editorial staff's willingness to work for insufficient pay.

Vangmayshobha thrived for 55 years because Kelkar treated it as a "laboratory to create literature," not a profit centre.

Regional literary magazines probably aren't economically sustainable in purely market terms. But honestly? Neither are museums. Or classical music performances. Or nature preserves. We sustain these because we collectively decide they have value beyond monetary return. We don't ask if museums are profitable - we fund them because we think they matter.

The real question isn't whether subscription models can save regional literary magazines. It's whether we, as a society, will choose to save them through whatever means necessary.

Do we believe that Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, and other Indian languages deserve robust literary ecosystems? Do we value the cultural memory these magazines preserve? Do we recognise that marginalised voices need platforms that commercial imperatives would never provide?

If yes, then we need to move beyond market logic to cultural commitment. Subsidise, donate, volunteer, subscribe - not because it makes economic sense but because it expresses our values. Because we've decided this matters.

The digital death of regional language magazines isn't inevitable. It's a choice we're making through collective inaction, through our willingness to let market forces determine what cultural resources survive.

Hans and its peers won't survive on subscriptions alone. They'll survive, if they survive, because enough people decide that Indian literature in Indian languages matters enough to make survival possible. Through government support, philanthropic funding, community organising, or sheer stubborn refusal to let these cultural institutions die.

The infrastructure is crumbling. The readership is ageing. The revenue models are broken.

But the mission - to create literature, to platform marginalised voices, to preserve linguistic heritage - remains as vital as ever.

Whether that mission survives the digital age depends not on finding the right subscription pricing or the perfect hybrid model. It depends on whether we recognise that some things are too important to be left to markets.

. . .

References:

- Hans (1930-present). Hindi literary magazine. New Delhi: Hans Prakashan.

- Sahay, S. (2019). Editorial statements and circulation data. Hans magazine internal documents.

- Yadav, R. (1986-2013). Editorial philosophy and mission statements. Hans magazine archives.

- Yadav, R. (2020-2024). Management transition reports and digital strategy documents. Hans Prakashan.

- Desh (1933-present). Bengali literary magazine. Kolkata: Anandabazar Patrika Limited.

- Vangmayshobha (1939-1992). Marathi literary magazine archives. Pune: Maharashtra State Archives.

- Indian Readership Survey (IRS). (2023-2024). Magazine circulation and readership trends report. Mumbai: Media Research Users Council (MRUC).

- Dentsu Aegis Network. (2024). India Digital Advertising Report 2024. Mumbai: Dentsu India.

- GroupM. (2024). This year, next year: India media and advertising predictions. Mumbai: GroupM India.

- FICCI-EY. (2024). Media and entertainment industry report: The era of consumer A.R.T. Mumbai: Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

- Dalmia, V. and Sadana, R. (Eds.). (2012). The Cambridge companion to modern Indian culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gopal, P. (2009). Literary radicalism in India: Gender, nation and the transition to independence. London: Routledge.

- Orsini, F. (2002). The Hindi public sphere 1920-1940: Language and literature in the age of nationalism. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Orsini, F. (Ed.). (2004). The history of the book in South Asia. London: Ashgate Publishing.

- Goswami, U. (2019, August 12). How Hans magazine is keeping Hindi literature alive. The Wire.

- Joshi, P. (2020, June 18). Regional magazines struggle to survive pandemic disruption. The Hindu.

- Krishnan, M. (2023, March 5). Death of the literary magazine: Can Indian regional publications survive digital disruption? Scroll. In.

- Pandey, G. (2021, April 22). Hans magazine: 90 years of Hindi literary activism. Live Mint.

- Sadana, R. (2018, November 10). The little magazine movement and regional literature in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 53(45), 45-52.

- Magzter Inc. (2024). Digital magazine subscription analytics: South Asia report. New York: Magzter Digital Publishing.

- Press Gazette. (2023). Global magazine circulation trends 2020-2023. London: Press Gazette Media.

- Hans Editorial Board. (2020). COVID-19 response and digital transition: Internal assessment report. New Delhi: Hans Prakashan.

- Kelkar, N.G. (1964-1992). Editorial notes and correspondence. Vangmayshobha archives, Maharashtra Sahitya Parishad.

- Premchand, M. (1930). Hans's founding editorial statement. Hans, 1(1), 1-3.

- Sahitya Akademi. (2022). Hindi literary magazines: A historical survey. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi Publications.

- Association of American Publishers. (2023). Literary magazine sustainability report. New York: AAP.

- Council of Literary Magazines and Presses. (2024). State of literary publishing. New York: CLMP.