There is a subtle pattern in every culture that many of us notice but rarely acknowledge, a logic of blame and forgiveness that is not grounded in truth or morality, but in power and position. It begins long before newspapers or social media pick up a story; it starts in small private spaces like families and classrooms, where the first lesson about who is allowed to make mistakes and who is not is taught without ceremony. In some households, when an elder assaults a younger relative, the instinct is not to investigate motives or ask uncomfortable questions about behaviour; the instinct is to preserve reputation, to close ranks and protect the family image. The younger one becomes the scapegoat, the one who must carry the guilt for something they may not have done, or at least not entirely, because saying otherwise could unravel the fragile social fabric the family fears more than truth itself. This is not about innocence or guilt; it is about fear. Fear of what neighbours might think, fear of gossip, fear of status being tarnished. The lesson that a child learns from that moment is not about justice; it is that truth is negotiable, and that powerful narratives are chosen not for fairness but for convenience. This lesson, learned inside the home, quietly travels with us into the wider world, shaping how we see victims and perpetrators, winners and outsiders, the powerful and the powerless. In the public arena, this dynamic becomes visible whenever society chooses to protect one person and punish another for the same act. What often changes is not the event itself but who committed it.

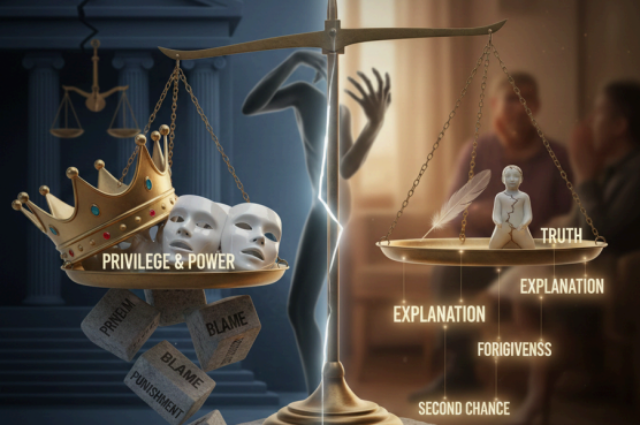

When something bad happens to a powerless person, society often responds instantly with blame, suspicion, and moral judgment, almost as if pain is evidence of guilt. A worker who makes a mistake loses their job and reputation in the same breath. A student caught in an exam dispute is labelled undisciplined or defiant without context. An ordinary driver involved in an accident is assumed negligent until proven otherwise, and even then some will whisper about irresponsibility rather than systemic issues like road design or vehicle safety. The speed with which people assume guilt in these cases is frightening and telling, because it reveals a default human reaction that is ignorant of context and hungry for a simple narrative. Yet when similar or even worse actions are committed by someone who is well known or well connected, the story changes. Suddenly, explanations emerge, intent is questioned, mitigating factors are invoked, and the narrative shifts toward protecting the individual. We hear about pressure, about reputation, about how no one is perfect, about how everyone makes mistakes. The imbalance is not always explicit. Sometimes it is subtle, carried in language rather than action. But it shapes outcomes just as powerfully as laws do.

This dynamic becomes even more visible when we look at how justice systems and public opinion interact with cases involving privilege. A globally discussed example is the Brock Turner case in the United States, where a young university athlete was convicted of sexual assault but received a shockingly lenient six-month sentence, serving only three months in jail. The judge in that case cited the defendant’s future and promise as a reason for a lighter sentence and emphasized his background and potential over the harm done to the victim. The public reaction was immediate and global, not because the incident was unheard of, but because it revealed how much difference a person’s status can make in how their wrongdoing is treated. In contrast, consider how often ordinary individuals, without networks, influence, or public sympathy, face harsh punishment for similar or lesser offences. The Brock Turner case did not happen in isolation; it is one among many where powerful individuals are met first with sympathy and second with accountability, and only reluctantly with consequences. The outrage that followed was not just about sexual assault itself but about how society instinctively protected someone with privilege and minimized harm while disregarding the suffering of someone without power. This case shows that when truth collides with privilege, truth is often the one that bends.

What connects these public patterns back to our private experiences is the way blame is distributed and pain is narrated. Inside many families, the younger member is asked to take responsibility because trouble is easier to contain that way. In society at large, the weaker party is blamed because it is more convenient and socially acceptable to dismiss their perspective than to confront structural inequalities. Powerful people are often given the benefit of doubt, not because evidence supports them but because power itself creates a container for ambiguity and excuses. When a wealthy corporate leader is accused of wrongdoing, headlines will temper the language, emphasising that investigations are ongoing and no conclusions should be drawn prematurely. Yet when an employee is accused of a similar act, their name is dragged through judgment before they even speak. When a public institution fails because of systemic negligence, we hear about bureaucratic challenges and resource constraints. But when an individual fails personally, we hear about character flaws and moral deficits. Blame and forgiveness are not accidental reactions; they are choices made collectively about who is worth defending and who is worth condemning.

This biased calculus also affects how we remember and forget stories. Some people’s faults stay on the front page far longer than others. Some careers end with a single accusation, while others pivot into new opportunities despite far more serious allegations. A celebrity with connections quietly absorbs scandal after scandal while ordinary people are defined by one mistake. A politician accused of corruption can still command rallies if their base is unshaken, but a street vendor accused of wrongdoing loses livelihood and dignity without public discussion. When this pattern is normalised, society begins to prioritize narrative convenience over truth, and the question of who has power becomes more important than the question of what actually happened. The innocent often become collateral damage in a social system that assumes context only when it benefits the powerful, and pain is only meaningful when it fits a comfortable story.

In education, similar patterns exist where students from influential backgrounds who violate rules sometimes receive gentle reprimands or second chances, while others face strict punishment for smaller infractions, as if belonging and connections buy immunity. In workplace environments, promotion may follow not ability but familiarity and status, and individuals who challenge norms are more likely to be excluded than those who conform despite being less competent. Across different domains, we see the same logic: when someone has power, connections, or social capital, they are granted the privilege of assumed innocence and contextual interpretation. When someone lacks those things, they are met with suspicion and immediate consequence. The yardstick of forgiveness becomes contingent on social leverage rather than universal values of justice or empathy, because society at large responds less to what is true and more to whom the truth belongs.

This is not to say that all powerful people are inherently protected or all powerless people are harshly judged, but society often defaults to these responses unless pushed otherwise by sustained reflection or visible consequence. Over time, this conditional empathy reshapes how people understand accountability, worth, and reputation. Instead of asking what happened, the first question becomes who is involved. Instead of exploring motives or systemic influences, the inquiry collapses into assumptions about character based on status. This shift in perspective undermines justice not because laws are weak, but because social instincts prioritise comfort over truth. It teaches young people early that vulnerability equates to blame and that strength equates to forgiveness. This is why even inside families, the younger one is sometimes told to apologise or remain silent, regardless of actual fault, because until truth is established, everyone around seeks ease over honesty. It is a pattern that travels outwards into society, shaping news headlines, judicial responses, public sympathy, and historical memory.

When we look at who gets forgiven and who gets blamed, it is clear that human prejudice plays a larger role than facts. Power is not only physical influence or wealth, but it is also narrative influence. It decides whose version of the story becomes dominant and whose is marginalised. Power decides who gets to explain themselves and who must simply endure assumptions. Power decides whether an error becomes a lesson or a social sentence. When we evaluate this dynamic honestly, we recognise that forgiveness in society is not an expression of compassion; it is an expression of convenience. Blame is not an outcome of investigation; it is the socially quickest way to protect comfort. Truth becomes negotiable not because it is complex, but because we choose to care more about how the story lands on us than how it actually unfolded. In that sense, perhaps the real question is not who is forgiven and who is blamed, but why society treats truth as a relative concept, pliable depending on privilege, familiarity, and fear of discomfort. And if we are willing to ask that question without fear, we might begin to imagine a society where accountability and empathy do not depend on power, where truth matters more than position, and where justice is measured not by who you are, but by what you know to be true.

Reference

- Time — Brock Turner Judge Faces Recall Campaign: https://time.com