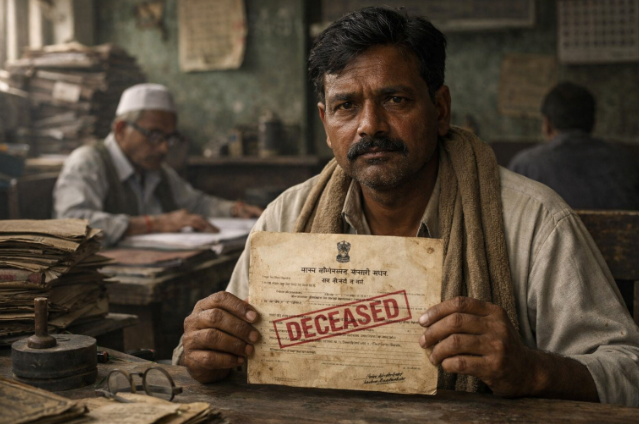

In 1975, a young weaver from the Azamgarh district of Uttar Pradesh, India, walked into a government office to apply for a bank loan. Lal Bihari needed the money to expand his small handloom business, but the clerk behind the desk delivered a message that was as absurd as it was terrifying: "You cannot have a loan. According to our records, Lal Bihari is dead."

Bihari was standing there—breathing and indignant—but in the eyes of the Indian bureaucracy, he had ceased to exist. He had been "murdered" on paper by his own uncle, who had bribed a local official to register Bihari as deceased to steal his share of ancestral land. This discovery sparked an 18-year odyssey that would see Lal Bihari transform from a victim into a world-renowned activist, eventually resorting to a "fake" murder just to prove he was alive.

The Bureaucracy of the Grave

Lal Bihari quickly realized that the Indian administration was a labyrinth of paper. If the revenue records said he was dead, no amount of physical presence would change the clerk's mind. To the system, he was a ghost. He was denied the right to vote, he could not hold a bank account, and he had no legal standing to reclaim his property.

Desperate to leave a paper trail of his existence, Bihari began a series of radical "crimes." He knew that if the state arrested and prosecuted him, they would be forced to acknowledge his living presence in court records. A dead man cannot be put on trial; therefore, an arrest warrant would be his "birth certificate."

The "Kidnapping" of a Child

The most sensational and desperate tactic Lal Bihari employed was the staged kidnapping of his nephew. He realized that a petty crime might be ignored, so he aimed for something that would force the police to act. He took his uncle’s young son—the child of the man who had stolen his identity—and disappeared with him.

He did not harm the child. Instead, he took the boy’s clothes, stained them with animal blood from a local butcher, and sent them back to the family. He publicly proclaimed that he had murdered the child in an act of revenge. He waited at home, expecting a swarm of police officers to handcuff him and record his name as a living suspect.

However, the plan backfired due to the very corruption he was fighting. His uncle, knowing that a police investigation would likely uncover the original land fraud and the fake death certificate, refused to file a police report. He preferred to let the child be "dead" in the eyes of the village rather than risk losing the stolen land. After a week, seeing that no charges were being filed, Lal Bihari was forced to return the child safely. Even as a self-proclaimed "murderer," the state refused to acknowledge he was alive.

The Birth of the Mritak Sangh

Bihari did not stop there. He added the word "Mritak" (meaning "deceased") to his name and founded the Mritak Sangh (Association of Dead People). He discovered he was not alone; thousands of people across India were victims of "paper murders" by relatives.

To keep the pressure on, he stood for elections against high-profile politicians, including former Prime Ministers Rajiv Gandhi and V.P. Singh. He filed nomination papers as a "dead man," forcing the electoral commission to grapple with his status. He even applied for a widow’s pension for his own wife, mockingly arguing that since the state considered him dead, she was entitled to government support.

The Resurrection

After 18 years of being a legal ghost, Lal Bihari finally won. On June 30, 1994, the Azamgarh district administration officially "resurrected" him in the revenue records. He had spent his prime years—from age 20 to 38—fighting for a right most people take for granted.

In 2003, his struggle was recognized with the Ig Nobel Peace Prize for his "posthumous" activism. His life story later inspired the 2021 film Kaagaz, bringing his fight against a blind system to a global audience. Today, Lal Bihari continues to lead the Mritak Sangh, representing thousands who remain trapped in the limbo between biological life and bureaucratic death.

Lal Bihari Mritak’s story is a chilling reminder of how easily a person’s rights can be erased by a corrupt pen. He proved that while the state can declare a man dead, it cannot silence a soul determined to be seen. He "killed" in name only to reclaim the life that was rightfully his.

. . .

References:

- The New York Times: Azamgarh Journal; Back to Life, to Fight for the Living Dead (2000)

- Time Magazine: Plight of the Living Dead (1999)

- BBC News: India's 'Living Dead' Fight for Rights (2000)

- Ig Nobel Prize: 2003 Peace Prize Winners

- Film Adaptation: Kaagaz (2021), directed by Satish Kaushik.