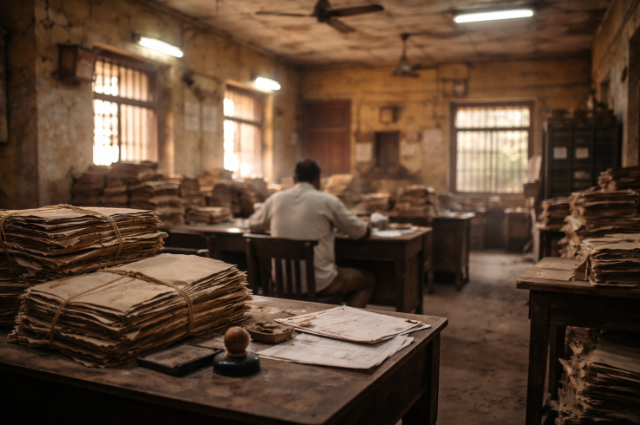

Some stories sound too theatrical to be real until you realise they unfolded under a government fan, in a dusty office where life and death could be decided with a stamp. Lal Bihari’s “death” began with no illness, no accident, just a ₹300 bribe and a lekhpal’s lazy stroke of the pen in rural Uttar Pradesh. Born in 1955, Lal Bihari was a young weaver in Azamgarh when he walked into a bank to apply for a handloom loan. Instead, he was told he had died.

On July 30, 1976, his name was struck off the revenue records, and his small ancestral plot was quietly transferred to his uncle, all for a ₹300 bribe. What do you do after dying on paper? Bihari wrote complaints, filed petitions, pleaded with clerks, but nothing moved. He learned quickly that bureaucracy rarely corrects its own mistakes, especially when they expose corruption. He was too alive to fit the file and too dead to fit the rules.

So, he did what the truly desperate do: he stopped playing by polite rules.

- He kidnapped his own nephew(the son of the uncle who stole his land), hoping police would be forced to register a case against a “dead” man.

- He urged his wife to apply for a widow's pension to make the contradiction official. He organised dharnas and even staged his own funeral procession shouting, “Mujhe zinda karo!” (“Make me alive!”). In 1989, he stormed into the Uttar Pradesh Assembly to repeat that cry before being dragged out. Most of these acts failed in courtrooms but succeeded in public consciousness.

In 1980, he added a word to his name, “Mritak” (deceased) and became Lal Bihari Mritak, wearing his bureaucratic wound like a badge. Turning personal tragedy into protest, he even jumped into politics. In 1988, he contested the Lok Sabha election from Allahabad against former Prime Minister V.P. Singh, astonishingly earning 1,600 votes. The next year, he filed against Rajiv Gandhi, then requested his own disqualification because he was officially dead. It was his way of forcing the state to confront its absurdity. For 19 exhausting years, he shuttled between offices, protests, and courts.

Finally, on June 30, 1994, District Magistrate Hausla Prasad Verma signed the order that brought him back to life. One signature resurrected him, undoing what a ₹300 bribe had stolen. Yet Lal Bihari chose not to reclaim his land, allowing his uncle to keep farming it. The struggle itself had become his purpose.

Then came a greater revelation: he was not alone. Across Uttar Pradesh, thousands had been declared “dead” on paper to grab land or inherit pensions. Lal Bihari turned his personal victory into a movement, founding the Mritak Sangh – The Uttar Pradesh Association of Dead People. It became a real union for the living dead citizens, erased from existence but still breathing, working, and paying taxes. By 2004, the group had secured “resurrections” for over 500 members and brought more than 20,000 such cases to light. His strange activism earned him global recognition and irony. In 2003, he received the Ig Nobel Peace Prize for “leading an active life despite being legally dead” and for creating an association of the deceased. Yet, true to the absurdity of his life, he couldn’t attend the Harvard ceremony because his documents blocked international travel. Eleven years later, he finally accepted the award at a Goa conclave, delivering a 20-minute speech instead of the allotted 1-minute Harvard version.

His story reached the cinema. In 2021, filmmaker Satish Kaushik turned his ordeal into Kaagaz (“Paper”), starring Pankaj Tripathi and produced by Salman Khan. Reviews were mixed; some found it poignant, others almost comic, but the story reached millions who’d never heard of bureaucratic death before.

It’s tempting to dismiss his experience as a relic of paper registers. But nothing essential has changed. Then, a lekhpal (clerk) could erase you with ink; now, one faulty database entry could delete your digital existence.

Under the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act of 2023, strict consent rules and correction timelines exist, yet human loopholes remain. A compromised Aadhaar or blocked account can still make a living person invisible.Even in his seventies, Lal Bihari refuses quietly. In 2023, he wrote to the Uttar Pradesh Chief Secretary demanding a licence for an AK-47 arguing, with dark humour, that if the state can call him dead, surely a “dead man” can be trusted with such a weapon. The request was rejected, but the act itself continued his theater of defiance.

In 2018, he petitioned the Allahabad High Court for ₹25 crore in compensation for 18 lost years, denied with penalties. Yet, in 2024, he remarried his wife, Karmi Devi a quiet reclaiming of the life bureaucracy once took away.Lal Bihari Mritak’s story remains a chilling mirror in a world ruled by documents, biometrics, and algorithms; to be alive is no longer just to breathe, it is to be correctly recorded. He forced the system to admit he existed. But for how many others will that resurrection never come?

. . .

References:

- Uttar Pradesh Association of Dead People https://en.wikipedia.org

- Lal Bihari https://en.wikipedia.org

- How A Farmer From UP Lived As A 'Dead Man' For 18 Years https://www.ndtv.com

- Lal Bihari Mritak To Celebrate 29th Rebirth Day On June 30 https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- Azamgarh native Lal Bihari 'Mritak' demands AK 47 license ... https://www.etvbharat.com

- Formerly Dead Lal Bihari Meets Fellow Ig Nobel Winners https://www.neatorama.com

- Kaagaz - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org

- THE DIGITAL PERSONAL DATA PROTECTION ACT, 2023 ... https://www.meity.gov.in

- Once declared dead, man struggles for compensation https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- नगालैंड से बिहार में करता था हथियारों की तस्करी, एनआईए ने एक https://navbharattimes.indiatimes.com

- Lal Bihari, born on May 6, 1955, in Amilo, Uttar Pradesh ... https://www.facebook.com

- List of Ig Nobel Prize winners https://en.wikipedia.org

- India Passes the Digital Personal Data Protection Rules https://www.privacyworld.blog