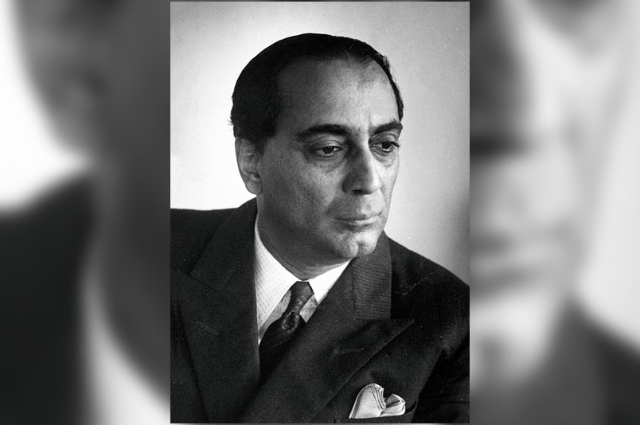

“Scientist, engineer, master-builder and administrator, steeped in humanities, in art and music, Homi was truly a complete man.” - J.R.D. Tata

In the heart of a young nation, where aspirations and challenges were beaming with vigour, a voice rose with unwavering clarity: “For the full industrialisation of the underdeveloped countries, for the continuation of our civilisation and its further development, atomic energy is not merely an aid, it is an absolute necessity.” These were the words of Homi J. Bhabha, whose vision would light the path for India’s ascent. Decades later, in a bustling, modern India, another voice echoed a parallel truth, reaffirming the vision built before independence. “Civil nuclear energy will ensure a significant contribution to the country's development in future,” declared Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Though separated by space and time, their words weave a common thread – nuclear energy in the service of the nation: a relentless pursuit of progress through science.

Today, having gone through the phases of demonstration, indigenisation, standardisation, consolidation and expansion, India has expertise in all aspects of operational nuclear power- from site selection, designing, construction, operation, maintenance, and modernisation to safe decommissioning. From a modest technological foundation in 1950 to 25 operational nuclear power plants with a total capacity of 8780 MWe in 2025, from an importer of technology to a creator and from a resource-deficient to a resource-efficient, India’s story of its scientific evolution captures many fascinating feats. And it all started with a visionary supernova, whose story is brought out in the pages that follow.

Seeds of a Scientific Culture

Born on October 30, 1909, to Meherbai and Jehangir, a wealthy Parsi family, at Kenilworth, his aunt’s bungalow at Peddar Road, Bombay (now Mumbai), he started showering his luminescence from his childhood- be it captivating his parents with a hyperactive mind or finding solace in the musical waves coming from the gramophone. Frequent visits to his uncle, Sir Dorabji Tata, brought him into the orbit of luminaries like Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, sparking in him a unique quest for modernity. His education at Cathedral and John Cannon High School, followed by Elphinstone College, honed his intellect. By 1926, he joined the Royal Institute of Science, Bombay, and a year later, he enrolled at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, to study Mechanical Engineering- a pragmatic choice shaped by his parents for a secure future.

But he soon discovered where his passion lies, which he described, in a letter, to his father in 1928- “I seriously say to you that business or a job as an engineer is not the thing for me. It is totally foreign to my nature and radically opposed to my temperament and opinions. Physics is my line. I know I shall do great things here. For each man can do best and excel in only that thing of which he is passionately fond, in which he believes, as I do, that he has the ability to do it, that he is, in fact, born and destined to do it. My success will not depend on what A or B thinks of me. My success will be what I make of my work. Besides, India is not a land where science cannot be carried on.”

With conditional approval- contingent on getting a first class in Mechanical Engineering Tripos, he pursued Mathematical Tripos. Bhabha passed both the Tripos with a first class, the former one in 1930 and the latter one in 1932. Then he published his first paper on absorption of cosmic rays1. He got an opportunity to meet Wolfgang Pauli (Austrian theoretical physicist) at Zurich, Neils Bohr (1922 Nobel Prize winner, physicist) at Copenhagen, Enrico Fermi (creator of the Chicago Pile-1) in Rome, Hans Kramers (Dutch physicist) in Utrecht and Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (1933 Nobel Prize winner, physicist) during his PhD under R.H. Fowler.

His Cambridge years were prolific. His Scattering Theory (published in the paper “The Passage of Fast Electrons and the Theory of Cosmic Showers” in Proceedings of the Royal Society) described the scattering of an electron and a positron, and now, it is used as a luminosity monitor in electron-positron collider physics experiments. The Bhabha-Heitler Theory explained the production of electron and positron showers in cosmic rays. He speculated on the Yukawa particle, coining the term “meson” and predicting relativistic time dilatation in meson decay. These achievements earned him international acclaim, thereby paving the way for interactions with other eminent scientists of the time. The friendships made and forged there illuminated his future endeavours. A short vacation in 1939 became a turning point for him and the nation. The outbreak of World War II made him stay in India, and so, he decided to join the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore.

A Commitment to Nation-Building

“Provided proper appreciation and financial support are forthcoming, it is the duty of people like us to stay in our own country and build up outstanding schools of research, such as some other countries are fortunate to possess.2”

At the IISc, he set up a Cosmic Ray Research Unit, mentoring young researchers in experimental and theoretical aspects of the research with the aid of balloons launched at varying altitudes. His work on classical relativistic spinning particles (Bhabha-Corben equations) and meson theory advanced elementary particle physics. Impressed by his work, Dr C.V. Raman nominated him for Fellowship of the Indian Academy of Sciences in 1940 and Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, London) in 1941. His theory of elementary particles and their interactions bagged him the Adams Prize in 1942. But he had the gaze extending beyond personal accolades. In a 1943 letter to his close friend J.R.D. Tata, he lamented: “The lack of proper conditions and intelligent financial support hampers the development of science in India at the pace the talent in the country would warrant.” Having tasted the intellectual freedom of Europe, he was determined to forge a scientific renaissance in India, even if it would mean stepping beyond the lab.

It was 12th March 1944 when he wrote to Sir Sorab Saklatvala, Chairman, Sir Dorabji Tata Trust- “I have for some time past nurtured the idea of founding a first-class school of research in the most advanced branches of physics in Bombay.... There is, at the moment in India, no big school of research in the fundamental problems of physics, both theoretical and experimental. There are, however, scattered all over India competent workers who are not doing as good work as they would do if brought together in one place under proper direction…I had the idea that after the war I would accept a job in a good university in Europe or America, because universities like Cambridge or Princeton provide an atmosphere that no place in India provides at the moment. But in the last two years, I have come more and more to the view that, provided proper appreciation and financial support are forthcoming, it is one’s duty to stay in one’s own country and build up schools comparable with those that other countries are fortunate in possessing…The scheme I am now submitting to you is but an embryo from which I hope to build up in the course of time a school of physics comparable with the best anywhere.”

A year before the world witnessed nuclear energy’s destructive power, he foresaw its potential for progress: “When nuclear energy has been successfully applied for power production in, say a couple of decades from now, India will not have to look abroad for its experts but will find them ready at hand. I do not think that anyone acquainted with scientific development in other countries would deny the need in India for such a school as I propose.” His vision, shared with “Bhai”- his affectionate term for Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru- laid the groundwork for a scientific revolution.

On April 14, 1945, the Trustees accepted his proposal and soon, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) was born with the support of the Bombay Government. Operating initially from IISc and later Kenilworth, TIFR published eight research papers- before its formal inauguration! With Bhabha, scientific work was assured as he, with his fellow scientists, would not wait for a particular building: “…ideas are some of the most important things in life, and men are prepared to suffer and die for them 3”

Post-Independence, he approached PM Nehru with a bold plan for atomic energy. With his outstanding advocacy skills, corroborated by the Atomic Energy Act, 1948, he treaded the path of scientific planning. On 26th April 1948, he prepared a note entitled ‘Organisation of Atomic Research in India’. Addressing the Prime Minister, he wrote: “…the development of atomic energy should be entrusted to a very small and high-powered body composed of say three people with executive power, and answerable directly to the Prime Minister without any intervening link. For brevity, this body may be referred to as the Atomic Energy Commission.”

Counting on him, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) came into being with Dr Homi J. Bhabha as its first Chairperson. Meanwhile, TIFR’s activities grew with time, and so did its offices. The Old Yacht Club near the Gateway of India served as one of its earlier offices. Recognising the need to have all operations under one roof, he wrote a letter to the PM requesting his approval for Navy Nagar, a land that belonged to the Ministry of Defence. His close relationship with the PM eased his burden for approvals, and he got what he had needed. On 1st January 1954, PM Jawaharlal Nehru laid the foundation stone for the new building of TIFR. Bhabha himself was immersed in its designing and construction activities- how can one forget he secured a first class in Mechanical Engineering.

Though work was going well at TIFR, there was a great need for power. A newly sovereign state could not depend on imports, be it in the form of technology or raw material, for generating power. Realising the need for energy security, Bhabha proposed the establishment of a nuclear research reactor on a barren land far from the lively city, but connected in terms of basic utility services. This project, Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay (AEET) was approved in 1954, and he became the Director of AEET. He planned every detail of it, from reactor design to campus aesthetics. Soon, recognising the ACE’s limitations, he proposed the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), which got established on 3rd August 1954 with Bhabha as its first Secretary. This streamlined structure, still in use, empowered the maverick scientists with their unconventional but meritorious ideas to bypass bureaucratic delays- a testament to his foresight.

As a deeply involved and visionary administrator, scientific thinker and subtle policy planner, he had curated a disciplined life for himself, reserving time for every component of his completeness. In a letter to Jessie Maver, he wrote: “I know quite clearly what I want out of life. Life and my emotions are the only things I am conscious of. I love consciousness of life, and I want as much of it as I can get.”

In a memorable presidential address at the first International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy held under the auspices of the UN in 1955, he reiterated the need of atomic energy for constructive purposes: “For the full industrialization of the underdeveloped countries, for the continuation of our civilisation and its further development, atomic energy is not merely an aid, it is an absolute necessity. The acquisition by man of the knowledge of how to release and use atomic energy must be recognised as the third great epoch in human history.” Reconnecting with his Cambridge rowing teammate W.B. Lewis, he forged international ties.

In January 1955, he visited Britain, where he met Sir Edwin Plowden (Chairman, Atomic Energy Authority) and Sir John Cockcroft (former colleague and then Director, Atomic Energy Establishment, Harwell) to explore the possibility of getting enriched fuel elements from Britain. In a letter to his mother, he wrote about this meeting: “…very satisfactory. This alone makes my trip worthwhile. It is now very probable that we will have an atomic reactor in India by the end of the year.” Except for the fuel rods, all components of the light water swimming pool type reactor, APSARA4 (the first reactor in Asia), were made indigenously. On attaining a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, he gifted his mother a one-rupee note inscribed: “Apsara First reached criticality 4 Aug ’56”.

At the Inauguration of the Atomic Energy Establishment and Swimming Pool Reactor on 20th January 1957, he noted: “A plentiful supply of energy is the first requirement of modern civilisation… If we are, therefore, not to lose further ground in the modern world, it is necessary for us to set up some atomic power stations within the coming five years, which will produce plutonium for our future power reactors, in addition to producing electricity now… The aim of the Department of Atomic Energy is to develop atomic energy as a source for electric power, and to promote its use in agriculture, biology, industry and medicine. On the industrial side, we intend to produce all the materials required for a full atomic power programme… Atomic energy is an unending trail leading into the future.”

To overcome the foreign dependence for enriched fuel elements, he proposed a heavy water reactor utilising his connection with W.B. Lewis. On 28th April 1956, India signed an agreement with Canada for an NRX-type reactor (in use at Chalk River, Canada). As it was decided to send our engineers to Canada for training, he made sure that they would not travel in the same aircraft. Initially called Canada India Reactor, it was later rechristened as CIRUS5 (Canada India Reactor Utility Services).

Bhabha engaged himself in multiple projects simultaneously. For an indigenous skilled manpower, he proposed the AEET Training School, which became a reality on August 19, 1957. Indigenous technology with indigenous human resources nourished with a network of friendship was working wonders among the scientific fraternity, thereby leading to cooperative, strong future association after graduating from the school. Meanwhile, he principally drafted the Government of India’s Scientific Policy Resolution, 1958. An indigenously designed and built computer, TIFRAC (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Automatic Calculator), was commissioned in 1960. CIRUS attained criticality on 10th July 1960, but problems started cropping up soon as the environment at Bombay was different from that of Chalk River- growth of algae in the primary water system, corrosion, rupturing of rods, etc- all problems were soon overcome by the Indian experts.

But one aspect was still awaiting solution- 100% indigenisation. For this, ZERLINA6 (Zero Energy Reactor for Lattice Investigation and New Assemblies) was built, and it attained criticality on January 14, 1961.

Beyond the Atoms

Bhabha’s brilliance transcended physics. He inspired people from multiple disciplines and let them have the requisite support. Post-Sputnik satellite launch, Dr Vikram Sarabhai strengthened his advocacy plans for India’s own space program. He contacted his close associate from IISc days, Dr Bhabha and both of them persuaded the Government of India to usher in an era of space research. In 1961, a space research division was started under DAE with Sarabhai as its in-charge. Bhabha played an instrumental role in setting up INCOSPAR7 (Indian National Committee on Space Research) under the chairmanship of Vikram Sarabhai and later the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station.

Similarly, he supported the proposal of four Indian radio astronomers who wanted to establish radio astronomy in India. Bhabha had realised the importance of electronics production when the seeds of the atomic energy program were sown in India. Therefore, he created an Electronics Production Unit at TIFR, which later moved to Trombay to support the functions at AEET. At the inauguration of the Nuclear Electronics Conference on 22nd November 1965, he remarked: “Our country came to realise rather belatedly in 1963 that electronics is not just something for the entertainment industry but one of the most vital and essential branches of modern technology.”

Another instance of embarking on a new project was in the field of molecular biology. In a lecture to the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), he recalled: “When, however, in 1962 my attention was drawn by the late Dr. Leo Szilard to a very promising Indian molecular biologist, it was decided to start work in microbiology which has since then been growing satisfactorily.” The promising molecular biologist was Obaid Siddiqi.

When the doctors of Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH) requested him to make TMH a part of DAE as they needed radioisotopes in radiation therapy used for treating cancer patients, he wrote to the PM accordingly. Consequently, TMH became an aided institution under DAE.

A polymath, he was likened to Leonardo da Vinci by C.V. Raman. In a letter to Jessie Maver in 1934, Bhabha wrote: “…But the span of one’s life is limited. What comes after death no one knows. Nor do I care. Since, therefore, I cannot increase the content of life by increasing its duration, I will increase it by increasing its intensity. Art, music, poetry and everything that I can do have this one purpose- increasing the intensity of my consciousness and life.” He sketched Sarojini Naidu, M.F. Husain and Blackett, among others.

Apart from sustainability and indigenisation, he had a great love for the pristine beauty of nature. SD Vaidya (in-charge of the parks and gardens in TIFR and AEET) recalled: “While planning roads in Trombay... The civil engineers had recommended the complete removal of the tree to have a straight road. Dr Bhabha felt that the tree which had lived there for over a hundred years had every right to continue to stay in the same spot... The tree had given character to the whole area for over a century and is still happily standing there as a living sculpture.”

An Enduring Vision

Tragically, on January 24, 1966, an Air India Boeing 707 crashed on Mont Blanc in the Alps, killing everyone on board. Prof. John Cockcroft mourned, “Human progress has always depended on the achievements of a few individuals of outstanding ability and creativeness. Homi Bhabha was one of these.” In honour of Bhabha, PM Indira Gandhi renamed AEET as BARC (Bhabha Atomic Research Centre) on January 12, 1967.

His three-stage nuclear power program remains a beacon - a fully operational third-stage nuclear power reactor is still elusive, though India’s first prototype Fast Breeder Reactor (PFBR) will be commissioned soon (marking the second stage of the nuclear power program). Having sailed through the restrictive trade practices and unilateral embargoes on nuclear supplies by certain countries, India now envisages a Nuclear Energy Mission for Viksit Bharat with a commitment to achieving 100 GW of nuclear energy capacity by 2047. Nuclear energy plays a pivotal role in the production of clean Hydrogen- a step closer to the Hydrogen economy. Harnessing nuclear energy to ensure long-term energy and food security8 reflects Bhabha’s vision: “The pursuit of science and its practical application are no longer subsidiary social activities today. Science forms the basis of our whole social structure, without which life as we know it would be inconceivable.”

Notes

Sreekantan, B. V., Virendra Singh and B. M. Udganokar, editors. Homi Jehangir Bhabha—Collected Scientific Papers. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 1985.

Bhabha wrote to the physicist S. Chandrasekhar at the University of Chicago.

From his speech, delivered at the inauguration of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research on December 19, 1945.

Permanently shut down in June, 2009 and gave way to APSARA-U (Upgraded) which achieved criticality on 10th September 2018.

After 50 years of successful operation, it was permanently shut down in December 2010.

Decommissioned in 1983.

INCOSPAR became ISRO in 1969 and later brought under the Department of Space

Food irradiation reduce food waste by extending shelf life and controlling spoilage

References and Bibliography

Homi J. Bhabha: Scientist, Visionary, Artist. Eminent Scientists Series, Public Awareness Division, Department of Atomic Energy, Anushakti Bhavan, Mumbai, 2021 (not for sale).

The Visionary and the Vision. A Permanent Exhibition, Homi Bhabha Auditorium, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 2009.

Tyagi, A.K. and P.R. Vasudeva Rao, editors. Atomic Energy in India: Achievements since Independence. Homi Bhabha National Institute, Mumbai, First, 2022.

Homi Jehangir Bhabha on Indian Science and the Atomic Energy Programme: A Selection. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, 2009.

Sethna, Dr. H.N. India's Atomic Energy Programme Past and Future. International Atomic Energy Agency Bulletin, Vol. 21-5, 1979.

Economic Survey 2024-25. Economic Division, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

Nuclear Power in the Union Budget 2025-26. - www.pib.gov.in