The Last Supper (1495–98) by Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most famous paintings in the world. The scene's composition is brilliant in its mammoth simplicity; the impact is amplified by the stark contrast in the moods of the 12 disciples as compared to Christ. The Last Supper, a classic of the Italian Renaissance Art and is one of the best-known pieces of Christian art, was painted by Leonardo da Vinci between 1495 and 1498. It depicts a scene from Jesus Christ's final days, as related in the Gospel of John 13:21. Christ's final dinner authorities who arrest him is the topic of the Last Supper. Two events are remembered from the Last Supper (a Passover Seder):

"One of you will betray me", Christ tells his disciples, and each of them reacts in his own unique way. Leonardo represents Philip asking, "Lord, is it I?" in reference to the Gospels. "He who dips his hand in the dish with me will betray me," Christ responds. Even as Judas reflexively backs away, we see Christ and Judas simultaneously reaching for a platter that stands between them.

At the same time, Leonardo depicts Christ blessing the bread and telling the apostles, "Take, eat; this is my corpse," as well as blessing the wine and telling them, "Drink from it all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for the remission of sins." These words mark the beginning of the Eucharistic sacrament (the miraculous transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ).

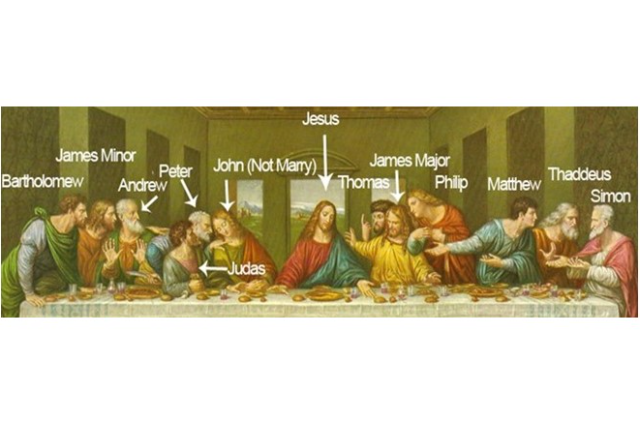

Identified Disciples:

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is full of allegorical connections. Each apostle is identified by his or her attributes. Judas Iscariot, for example, is identified as he reaches for a dish alongside Christ (Matthew 26) and as he clutches a bag containing his payment for identifying Christ to the authorities the next day (Matthew 27). Peter, who sits next to Judas, has a knife in his right hand, implying that he will sever a soldier's ear in order to shield Christ from arrest.

Heavenly recommendations:

An equilateral triangle formed by Christ's body anchors the balanced composition. He is seated beneath an overhanging gable that, when finished, would form a circle. These ideal geometric forms allude to Neorenaissance Platonism's popularity (an element of the humanist revival that reconciles aspects of Greek philosophy with Christian theology). Plato, the Ancient Greek philosopher, stressed the inadequacy of the terrestrial realm in his allegory "The Cave."

Leonardo employed geometry, which the Greeks used to depict heavenly perfection, to honor Christ as the earthly manifestation of heaven.

Beyond the windows, Leonardo painted a lush landscape. It has been suggested that this celestial sanctuary, which is sometimes regarded as paradise, can only be attained via Christ. The twelve apostles are divided into four groups of three, with three windows in between. In Catholic art, the number three frequently refers to the Holy Trinity. The number four, on the other hand, is significant in the classical tradition (e.g., Plato's four virtues).

Condition:

The Last Supper is in a deplorable state of preservation. The artwork began to fade soon after it was completed on February 9, 1498. "...the picture is all wrecked," said Giovan Paulo Lomazzo in the second half of the sixteenth century. The painting's state has been severely harmed over the last 500 years due to its location, the materials and strategies employed, humidity, dust, and poor restoration efforts. A bomb exploded in the monastery on August 16, 1943, damaging a big piece of the refectory, severe air pollution in postwar Milan, and ultimately, the impact of overcrowding tourists.

Leonardo covered the wall with a double layer of dry plaster to obtain greater intricacy and brilliance than could be accomplished with ordinary paint. Then, taking a cue from panel painting, he layered a lead white undercoat to bring out the brilliance of the oil and tempera on top. Because the artwork is on a thin external wall, the effects of dampness were amplified, and the paint failed to stick to the facade correctly.

These initial restoration efforts, as well as the artwork's placement (the church is in a flood-prone area), the resources and methodologies Leonardo used, Napoleon's army's occupation (who reportedly stabled their horses in the refectory and reportedly lobbed bricks at the apostles' heads), moisture content, dust, poor air quality, and, most recently, the influence of crowding international visitors, have all harmed the painting's condition over the last 500 years.

The Last Supper is an excellent example of how public and professional attitudes about restoration initiatives are not only divisive but also shift through time. Whereas restorations in the nineteenth century and earlier relied on overpainting to create the illusion of a totally finished work, newer techniques prioritize exposing missing sections and making all modifications clear and explicit. The current rendition of Leonardo's Last Supper bears little resemblance to the original, but it reveals the painting's remarkable and torturous past.