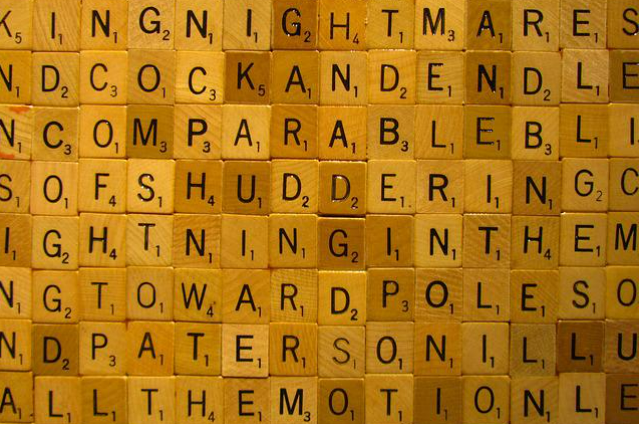

"Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe."

This paragraph was circulated on the Internet several years ago. The phenomenon it describes, known as typoglycemia, is the ability to understand words when the first and last letters are stable, but the intermediate letters are scrambled. Our brain puts the letters back into a sequence again.

According to Ashwini Nadkarni, Director of Digital Integrated Care in Psychiatry and Instructor at Harvard Medical School, typoglycemia is a newly coined word made up from the prefix 'typo' and the suffix 'glycemia'. Typoglycemia enables us to recognize words by just looking at the exterior letters. She says, 'As long as the exterior letters of the words remain the same, typoglycemia captures our preserved ability to comprehend them.'

Chunking is actually a cognitive shortcut that our brain uses to divide information into more meaningful parts so that the information can be recalled more effectively. It can also be regarded as a mnemonic device. For example, when we want to speed read a page, we might utilize chunking by breaking down the page into individual paragraphs, then reading each paragraph by comprehending it as a single unit rather than a string of sentences. Similarly, in chunking, we read and comprehend individual words as a whole. These are actually the ways in which our brain works on information.

Dr. Margaret King, Director of Analytical Studies in Philadelphia, 'The visual world is perceived by the senses and then simultaneously constructed by the brain to make sense - based on pattern recognition, prior knowledge and experience. This explains how we can look at a string of scrambled letters and still be able to see the dominant patters in them, that is, the first and final letters. Our brains are able to fill in the blanks ( the de-arranged letters ), an editing process that now makes the words fit our expectations and projections.'

We always tend to chunk information for better retention and memory. Like in order to remember the birthday of Napoleon of France (15th August, 1769 ), we can co-relate it with the Independence Day of India (15th August, 1947 ).

The date of resignation of Soviet Statesman, Mikhail Gorbhachev can be related with Christmas Day, 1991.

Like to remember the colours of Spectrum, we popularly use 'VIBGYOR'.

These are just few examples. There can be many more. And I am sure that many of you must have done it in your life atleast for once.

Chunking allows us to group meaningful information into clusters so that this information is retained for a longer period of time. Chunking is also related with relational learning but we may end up relating things in such a way even if the information is not relevant to all of them.

Chunking is generally used when we try remembering the long sequences of information. The students of History use it very frequently. It can also be described as a learning movement.

It's also true that not all jumbled words can be arranged in a correct order by brain. The process of chunking mentioned above is somewhat related to the ability of brain to 'join the dots'.

It's helpful for anxiety management. Anxiety disrupts our thinking ability. Chunking can help the prefrontal cortex of brain to regain it's stability. Undubitably, it helps for the easy procession of information.

People who try to read by pronouncing each word letter by letter is a result of the fact that people have lost their capacity to read words as a whole. Probably, this can happen when people suffer from brain strokes ( or their basal ganglia - the part of brain responsible for chunking ) has been destroyed. Pure alexia results from damage to neural mechanisms in the left occipital temporal region, which is uniquely tuned for word recognition.

Pablo Solomon contents that chunking is associated with 'profiling' which may give it a negative connotation. Profiling is exactly what our brain does by automatically and at amazing speed, putting together an evaluation of people we meet and new situations. Actually, chunking can also be regarded as the ability of the brain to fill in the blanks by seeing the 'larger picture'.

By separating disparate individual elements into larger blocks, information becomes easier to retain and recall. This is due mainly to how limited our short-term memory can be. While some research suggests people are capable of storing between five and units of information, more recent research posits that short-term memory has a capacity for about four chunks of information. Chunking allows people to take smaller bits of information and combine them into more meaningful, and therefore, more memorable wholes.

Chunking can be used with challenging texts of any length. The students must review reading strategies before they work on paraphrasing the text. The paraphrased text can be used to evaluate students understanding and reading ability. This step often leads to interesting discussions about interpretation - how people can often find different meaning in the same words. Chunking helps you overcome the natural limitations of your memory, and is therefore a very powerful trick for helping us to learn information and get it into memory.

Typoglycemia may sound similar to it's rhyming reference - hypoglycemia. Although typoglycemia sounds like a medical term, it is not related in any way to glycemia, the presence of glucose in the bloodstream.

It is a term given to a purported recent discovery about the cognitive processes behind reading written text. It is based on cognitive abilities are brain-based skills we need to carry out any task from the simplest to the most complex. They have more to do with the mechanisms of how we learn, remember, problem-solve, and pay attention rather than with any actual knowledge.