In 1993, Kevin Carter took an iconic photograph of a girl (later discovered to be a boy) and a vulture during the Sudan Famine. He called the shot a powerful set of symbols. The photograph earned him a Pulitzer Prize, but tragically, four months later, he took his own life. He was 33. “I’m really, really sorry... The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist," he wrote in the note he left behind.

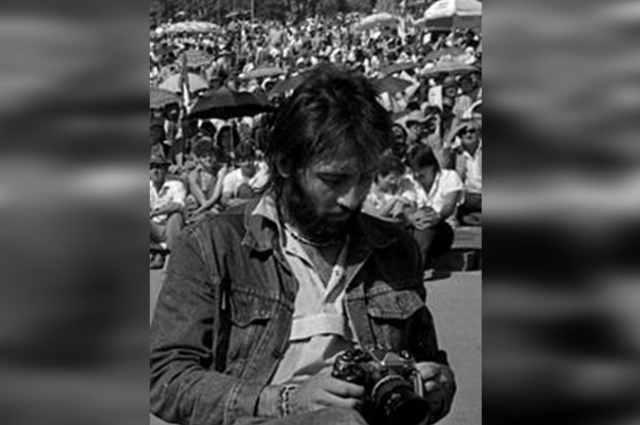

Life and Death of Kevin Carter:

Kevin Carter was a South African who grew up seeing the harsh treatment of black people by police. He grew up in a middle-class family in an all-white locality. He felt anguished by his family’s laid-back attitude towards this issue. He first studied pharmacy but was drafted into the army, where he served for 4 years. In an incident involving defending a black mess-hall waiter, he got beaten by other servicemen very badly and went on leave without notice. Carter dropped out eventually, fled to become a DJ, and changed his name to David. But then he found a camera and decided to become a photojournalist. He initially worked as a sports photographer and then worked for the Johannesburg Star to expose the Apartheid regime.

He was the first photographer to document the public execution of a victim named Maki Skosana. About which he said,

"I was appalled at what they were doing. But then people started talking about those pictures, and then I felt that maybe my actions hadn't been at all bad. Being a witness to something this horrible wasn't necessarily such a bad thing to do."

He is known to have captured images of many dead people, starving children, and violent acts. He was also a member of the Bang Bang Club, a group of four photographers working in South Africa from 1990 to 1994. The other members were his best friend Ken Oostoerbroek, as well as his friends Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva. Kevin Carter was a father to a girl named Megan.

On an assignment, he and his friend Joao Silva flew to Sudan, a country that was struck by famine at the time. There, he shot the prize-winning picture known as "The Struggling Girl and the Vulture." The photograph depicted a starving girl holding her skull, as if unable to bear its weight anymore, with a vulture calmly waiting nearby with folded wings, ready to feed on her. The girl was on her way to the feeding center. It is said that Carter chased the vulture away and then cried under a tree, thinking of his daughter and wishing he could hug her.

The Vulture And The Little Girl, captured during the Sudan famine of 1993 by Kevin Carter.

The photo was later bought and published by The New York Times. People's reactions to the photo were very strong, with many inquiring what had happened to the girl. Posing questions regarding the photographer's compassion and whether or not he took any action to assist the girl.

Later, the paper had to publish a follow-up, saying, “The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she reached the [feeding] center.”

Carter used to be depressed forever after, recalling the horrible suffering and murder of the people there and finding it difficult to get out of bed. He was afflicted after hearing from others that he ought to have helped the girl. It crushed him.

In April 1994, he won a Pulitzer Prize for the picture. The picture gave Carter not only success but also ridicule. The photo made people question the ethics and empathy of the ones capturing the horror. The picture begged the viewers to act, but they failed miserably. A week later, his best friend, Ken Oosterbroek, was shot and killed. He was devastated, telling people he should have died, not Oosterbroek. He turned down assignments and offers because he couldn't get out of bed. The vulture from the photo was haunting him.

Four months later, Carter drove to a park, ran a hose from the exhaust pipe into his car, and died of carbon monoxide poisoning. He brought awareness to the world and left a mark on human consciousness, but at a price.

In his note he wrote, “I'm really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist... depressed… without phone… money for rent… money for child support… money for debts… money!!! I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain… of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners… I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”

In the Massachusetts review: Killing the Messenger, a journal article by Sean Thomas Dougherty writes:

“The photo exists in the present tense. Carter's photo begs the viewer to act. Why then why was it met with such public critique as unethical? Because it worked. People felt horror, empathy, anger. But without the ability to act, without the necessary political apparatus to do something, so many turned, as in ancient Greece, and attacked the messenger.”

A few years later, a journalist travelled to Sudan to track that girl from the picture, and it turns out that the child was actually a boy, and his name was Kong Nyong. According to his father, Kong Nyong had survived the famine but died later due to an unrelated illness.

As a tribute to Kevin Carter, A documentary titled The Death of Kevin Carter: Casualty of the Bang Bang Club was later created by Dan Krauss, which covers the life and death of Kevin Carter. The documentary garnered a nomination for best short documentary and also won four awards on the US film festival circuit.

Conclusion:

Carter's death is synonymous with the issue professionals face today: not doing what is not part of their job. The medium supposed to influence people and change their perceptions is often criticised. Should they remain mere observers and report what they have seen, or should they get involved in the situation? This is a question that is often raised. When we see a picture, it is natural for us to empathise and ask, "What happened? Did you help them?" However, journalists and other professionals in the field have to keep their emotions in check, do their job, and spread the message so that action is taken on an international level. Carter's death also highlights the consequences of witnessing raw pain, anger, and death.