“In another moment down went Alice after it

without considering how in the world

she was to get out again.”

- (Alice in Wonderland)

The replication of reality seems to have been the major source of inspiration for the early generations of game-makers. It is what propelled their imagination and the effort that went in that direction piled up over time to engineer virtual environments that mimicked the real ones. But with this came the growing concern about reality bleeding into the virtual and films like The Matrix (1999) only served to add fuel to the fire, or flare up the imagination depending on which side of the spectrum people fell on. Speculations about the existence of a matrix, an inane but influential notion nonetheless, began to question the ideas of free will and fatalism took on a new meaning. If it were true, the word organic did not mean anything because, like characters on the screen, in gameplay, and animation, we were also the product of an algorithmic framework and the naturally occurring and changing cultures, topography, geography, and architecture was not the product of human technological evolution but of tweaks in codes written on a computer screen that predetermines our fates. We were not fate-bound but chained to a sequence of binaries. There were no infinite possibilities but two, zero, and one.

From games that strove to replicate reality, to games that got so close to replicating reality that they shook the foundations of our worldview, we have drifted to a liminal space, where foregrounding the differences between virtual and real has become crucial. The games have become something of an institution in themselves, so much so, that a flourishing body of literature has developed around gameplay, and we have websites like ‘Fandom’ dedicated specifically to documenting the characters in games with a detailed description of the narrative of the gameplay. The imitation of reality has gotten more and more detailed over time, to the extent that game-makers do extensive research and make replicas of cultures, and history, and narrativize the game to suit a historical context, a biological one, or an architectural one. These consistencies have resulted from years of continual development, but these very consistencies have given rise to alarming situations. People tend to gravitate more toward these advanced and environmentally immersive games and fall prey to pathological gaming (which can result in the impairment of an individual’s ability to function), and it is for this reason that we need to wedge a gap between the real and the virtual.

It is within the framework of this argument, that this paper talks about a game released by Ubisoft in 2012, called Far Cry 3, and how it simultaneously constructs reality through layers of environmental, cultural, and architectural features, but leaves enough breadcrumbs and caveats within the gameplay to remind the player of its fantastical nature. It encapsulates within it the seeds for its deconstruction. The game tries to suck the player into a vortex of infinite possibilities but also forces the player to realize its ephemerality and unreality. It is by placing these two perspectives simultaneously, that I want to analyze, the paradoxical nature of the erection and demolition of reality that happens within the gameplay, and how we have reached a stage in the development of the games, that players need to be reminded of the non-actuality of videogames.

1. THE CONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

In regards to the accurate portrayal of the environment, Alenda Y. Chang writes, “that attention to ecological details can make for not only a more responsible gaming experience but also a more compelling one” (Chang 61) She further writes that “it can be frustrating from the developmental standpoint” to insert biotic and abiotic factors into the game environment. But games that truly seek to mimic reality must mimic it with all its limitations, including the insertion of biotic and abiotic factors.

The environmental realism, which breaks away from the tradition of the inert and non-interactive environment allows the player to converse with the natural order and learn about the flora and fauna of the region. Far Cry 3 for instance, is set in an archipelago called the Rook Islands, where our protagonist Jason Brody is stuck because of unfortunate circumstances (his brother has been murdered and his friends are held hostage by the people who run the island), and must master the terrain and learn about the cultural and biological eco-system of the place to survive and exact revenge for his brother's death.

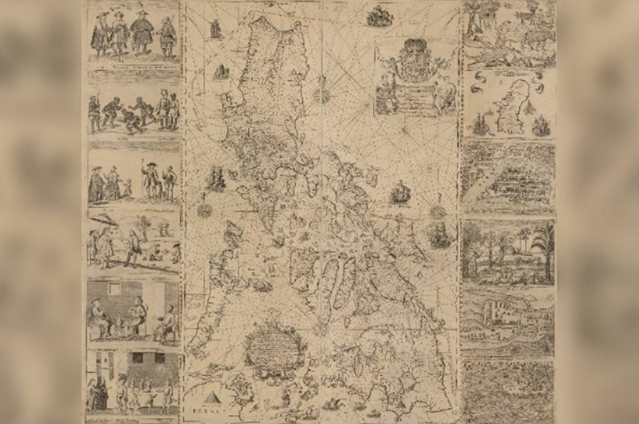

The creation of the island draws inspiration from a bunch of Polynesian islands, the primary ones being Indonesia and the small Polynesian island of Tonga. The native people of the Island, the Rakyat, were the initial inhabitants and shared a symbiotic relationship with the environment and remained relatively undisturbed for centuries. The peace of the Islands is shattered when Hoyt Volker a South African drug lord raises a mercenary army (called Privateers) and takes control of the Island. He lays down an extensive network of the drug trade, human trafficking, and arms deals and operates from the anonymity of the dense forests of the Islands protected by his private army and away from national jurisdictions. His ruthless attitude brings him into constant conflict with the native population, and his vitriolic nature finds expression in the form of Vaas Montenegro, his right-hand man, and as we learn through the course of the game, a Rakyat himself.

Now, the game itself abstains from making any explicit commentary about the dark underbelly of colonialism and concerns itself mostly with the dealings of Jason Brody, and his quest for retribution on Vaas for killing his brother. But as the story unfolds, we are led down a rabbit hole of cause-and-effect kind of scenarios, where we are confronted with the fact that Vaas along with the other inhabitants of the Islands are victims of Hoyt, and what we are witnessing is the initial stages of the colonial project.

1.1 COLONIZATION AND THE THEORY OF COMPETITIVE EXCLUSION

What's happening on the Island, the natives being pushed to the brink of extinction, for a project that is explicitly capitalistic and seeks to weed out the cultural ecosystem of the place mirrors a theory in ecology called the "Theory of Competitive Exclusion." The theory follows a mathematical model proposed by Volterra that, "the indefinite co-existence of two or more species limited by the same resources is impossible" (Armstrong & McGehee 151). Cole writes, that "one or two sympatric species occupying the same niche" and the same trophic level (position on the food chain), cannot coexist. The species more likely to survive in such scenarios is usually determined by the persistence and advantage (physiological, morphological, or predatorial), that one organism has over the other (Cole 348). There is a similar and almost parallel shift that happens within the cultural ecosystem of the island. When a foreign element in the shape of Hoyt Volker is introduced into the cultural ecosystem, we find that the invasive species instantly takes over the island, and plunges the native population into mindless violence. The ecosystem thus disrupted must make transformations to accommodate the new invasive species. Also, with the influx of the foreign corrupting element, we find that the social fabric of Rakyat has been irreparably scarred. Volker turns the natives against each other, the primary example being Vaas Montenegro who kills his own people for Hoyt. So, a cultural ecosystem that remained virtually untouched for centuries with occasional invasions from the Chinese and the Japanese soldiers stationed on the Island during World War II, must suddenly undergo a violent structural transformation, to protect their island and resources.

The resistance against Hoyt comes from a small hamlet on the island called Amanaki Village. The word Amanaki comes from the Tonga language which means hope. The woman leading the resistance is the high priestess of a temple and Vass's sister, Citra Talugmai. She is the leader of the Rakyat and the handbook in the game mentions that her temple is both a place of worship and a stronghold of the Rakyats.

1.2 ARCHITECTURAL REALISM

Citra's temple, along with other structural elements that are strewn around the archipelago shows a kind of morphological development in architecture that displays a remarkable attention to details paid by the creators. Morphology in architecture refers to changes in the formal syntax of buildings and places as their relationship to people evolves and changes. The range of architectural variety that exists, aligns with the influx of different cultures across the ages and serves to add another dimension to environmental realism.

The Chinese subterranean temples and catacombs, which serve as the location for Jason Brody's quest for the ‘Silver dragon’ (a dagger buried with Lin Cong, the Chinese general) are full of perils every step of the way, and the structure itself seems to be precariously hung. It is the remnant of a culture that was once there, that once enslaved the island and its people but has now been quite literally driven underground. The next phase in the development comes from within the native population in the shape of Citra's temple, and the design seems to be influenced heavily by the Hindu and Buddhist temples in Cambodia and Thailand. It stands as a symbol of resistance and is quite possibly one of the sturdiest buildings on the Island. Then there are military bunkers in certain places on the Island, the vestiges of World War II, and the Japanese army's presence. They have also been taken over by vegetation suggesting the gradual erosion of the Japanese presence on the Island. We also find small settlements of the Rakyat's people on the Island, who as the game progresses, with the help of Jason Brody begin to reclaim the Island and form more settlements. This reclamation is representative of the gradual resurgence of the native culture and its simultaneous moves toward globalization and away from colonialism.

So, the Island and its architectural features sprouting within the dense subtropical vegetation, and the attention to languages, display a range of cultural influences, and the game makers' conscious effort to not only understand the history of the region, which the makers assess accurately to a certain degree but concoct a kind of historical continuity that is congruent with the actual history of the Polynesian Islands.

2. THE DECONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

The game spends a whole lot of time, and energy fabricating reality, through a painful sequence of zeros and ones, and then plants breadcrumbs within the narrative, to deconstruct it. The animals in the games have a unique ability to stick to their trophic level, as it exists in the outside world. A carnivorous like a tiger or a Komodo dragon, if it sees the player will attack him, and if it’s an herbivore like a boar or a deer for instance, will most likely run away from him. But all this time and energy spent on creating an ecologically exact environment, and providing the animals with AI, only for us to realize that the character Jason Brody, is under the influence of drugs the entire time, and not everything he sees, listens to, or hears is entirely accurate.

It blows a major dent into the believability of the storyline, and we slowly begin to drift into a space of growing doubt. Curtis Silver, in an article titled, ‘Far Cry 3 Drops The Narrative Down The Rabbit Hole,’ writes that “Jason’s trip down the rabbit hole (a reference to Alice in Wonderland) won’t be obvious to players unless they actively try to hunt for clues and engage with the gameplay” and that “not only is it painfully obvious what is happening, but the game literally tells you at certain points, through interactions with other characters” that it might just be the fabrications of a mind that is high on drugs (Silver NA). The hallucinating sequences within the gameplay reflect Jason’s destabilizing psyche, and his ever-growing appetite for killing only highlights that he is straying further away from sanity.

The game’s creator Jeffery Yohalem mentions, that these subtle indications encrusted within the storyline, ask the player why they would willingly trap themselves in a beautifully crafted but virtual environment instead of a real one.

Another instance where the realism of the narrative seems to crumble down is when Jason Brody, a relatively ordinary person, is thrust into an alien and inhospitable environment. Still, he quickly amasses combat skills, stealth abilities, and survival instincts that surpass what would be ordinarily expected from an untrained individual. Then we have this larger-than-life antagonist, in the shape of Hoyt Volker, who exhibits extreme levels of sadism, brutality, and unpredictability. He is the classic example of a brutal dictator, who mercilessly kills anything and everything that stands in his way, and yet time and again, we find him, either unable to zero in on Jason Brody, or Brody making a narrow escape. Finally, when Brody confronts him, and stabs the knife into his heart, in a visually hallucinatory sequence, we never find Hoyt’s dead body, reaffirming Silver’s argument about the whole narrative being the fabrications of a hallucinating mind.

The game, as I have mentioned earlier, draws heavily from Lewis Carrol’s ‘Alice in Wonderland.’ The Loading screen of the game is filled with quotes from the book, like “I like the walrus best said Alice: “Because you see he was a little sorry for the poor oyster”.” The fact that Jason Brody is hallucinating cannot be made clearer, as it’s fairly obvious that he is suffering from “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS).” Nancy Hammond writes, “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome is a neurological condition that causes perceptual disturbances. This can include sight, touch, and time…It’s a rare condition that temporarily changes how the brain perceives things” (Hammond, para1). The syndrome can result from, either the use of psychoactive drugs, viral infections (Epstein-Barr Viral infection), or temporal lobe epilepsy.

In our protagonist’s case, it most likely results from the excessive use of psychoactive drugs, and is catalyzed by an inclination to perform feats that align with the dominant notion of masculinity i.e., the capability to cast violence, perform impossible physical feats, and save the proverbial princess in the castle. He is possibly even a schizophrenic, who creates characters in his head to satiate his repressed desires to become more masculine (whatever the Western conventional definition of masculinity encapsulates).

Picture by: unsplash.com

This construction and deconstruction of reality which the game makers engineer, with the intent as Yohalem mentions, to remind the player of its artificiality harks to the Brechtian notion of the alienation effect. The alienation effect Josette writes, is “a process by which both theatrical and extra-theatrical phenomena are rendered strange forcing the spectator to adopt a critical distance…” (Féral 461). That is exactly the gap, the critical distance we need to wedge between the virtual and the real, to alienate the gamers, not from their immediate reality, but from the artificiality of the digital world, so that they can make critical and informed decisions, and not be amputated or impaired by pathological gaming. Far Cry 3, goes a long way in terms of creating that space for the realization of the non-actuality of video games. The artificiality of the environment is written on the wall but is hidden behind a thicket of data that layers the veneer of reality over it. And it is this scraping of veneer, this realization of disintegrating reality that the game wants the player to execute, and therein lies the brilliance of its narrative.

References:

- Armstrong Robert A., and McGehee Richard. "Competitive Exclusion." The American Naturalist 115.2 (1980): 151-170. Digital File. May 2023. .

- Chang, Alenda Y. "Games as Environmental Texts." Duke University Press 19.2 (2011): 56-84. Digital File. May 2023.

- Cole, Lamont C. "Competitive Exclusion." Science AAAS 132.3423 (1960): 348-349. Digital File. May 2023.

- Féral Josette, Ron Bermingham. "Alienation Theory in Multi-Media Performance." The Theatre Journal 39.4 (1987): 461-472. Digital File. May 2023.

- Hammond, Nancy. What is Alice in Wonderland Syndrome? 23 June 2020. Digital File. May 2023.

- Silver, Curtis. Far Cry 3 Drops the Narrative Down the Rabbit Hole. 15 Jan 2013. Digital File. May 2023.