Philosophical traditions across the world deal with the quest for the nature of truth, of ethics, or the perception of reality and indulge in testing positions, postulating arguments, or correcting distortions within an argument. The Indian philosophical system deals primarily with concepts such as the view of samsara, the origins of dukkha, of dharma, of karma, of renunciation, and of meditation with its ultimate objective being the attainment of what has variously been referred to as Nirvana, Moksha (liberation from samsara and dukkha), and Kaivalya (realization of separateness or aloneness) within the various schools of Indian philosophy like Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism.

The Indian philosophical system bifurcates into two branches of thought depending on three primary factors-whether it believes in the authority of the Veda as the ultimate source of knowledge and Apauruseya (composed by a non-human\divine entity); whether it believes in reality as composed of Brahman and Atman; and whether it believes in the notion of the after-life and devas. The two classifications into which it bifurcates form the āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy. The āstika school which believes in the authority of the Vedas can be further subdivided into six separate darshans (shat-darshan)- Sānkhya, Nyaya, Yoga, Vaisheshika, Purva Mimamsa, and Uttara Mimamsa. Whereas, the primary sub-divisions of the nāstika school fall into four categories- Buddhism, Jainism, Chārvāka, and Ājīvika.

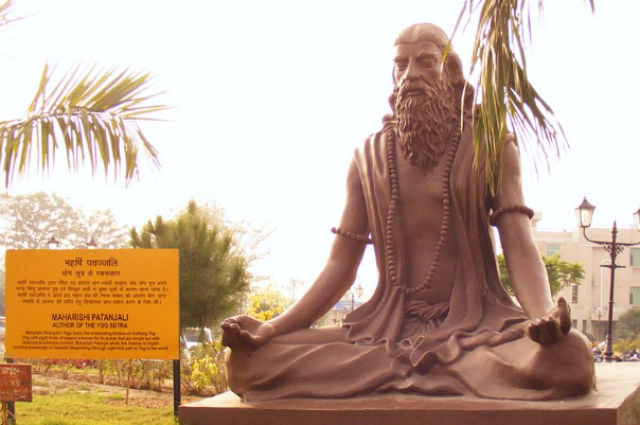

Samkhya and Yoga philosophies branch out from the Āstika or the six orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy (Shad-darshan). The two concepts though disparate and espousing different views in their own right, share a lot of similarities and converge at multiple points. The term yoga, within the Indian philosophical system, finds a broad expression, in the form of Patanjali’s seminal text, Yoga Sutra and Hath Yoga Pradipika written by Svātmārāma in the 15th CE. Mentions of Yoga can be found in the Shrimad Bhagavatam, and Vyasa’s commentary on Patanjali’s Yoga sutra, in the form of Yoga Bhasya.

Samkhya similarly, provides a metaphysical extension to the views espoused by Yoga, with their ultimate goal converging at the realization of the dualism that reality encapsulates i.e., Purusha and Prakriti. Samkhya Karika, written by Ishvara Krishna contains 72 Slokas and delves into the exploration of the two aspects that constitute reality and the pramanas (proof) through which jnana-Prapti (absorption of knowledge) could happen along with deliberations on right and false perception.

Yoga helps in the realization of this dualism by helping the yogi attain a state of samadhi (complete absorption), which allows the yogi to gain mastery over the chitta. This allows for Sant(tranquillity) and Udita (reason) to occupy the Yogi’s mind which eventually bestows upon them the capability of discernment. The complete disentanglement of the two, Purusha and Prakriti, is fundamental to both the schools of Hindu philosophy, and Patanjali in his Yoga Sutra’s Vibhuti pada sutra 56, states that:

||Sattvapurushayoh shuddhisamye kaivalyam iti||

Vivekanand’s commentary on the very same mentions that, once the atman (soul) realizes that it is separate and divorced from everything in the universe, “from Gods to the lowest atom,” it achieves a state called Kaivalya or complete isolation and uncontaminated perfection.

Moksha is another important element that the two philosophies share in common for it is through the attainment of Kaivalya (capability to discern) that one can hope to attain moksha. Now regarding moksha (here, liberation from the cycle of Birth and rebirth), Patanjali in Samadhi Pada sutra 21, writes:

|| tivra-samveganam-asannah||

Meaning, those who seek moksha through either sraddha (faith), virya (energy), smriti (memory), samadhi (oneness), prajna (wisdom), and itaresam (from others), and seek liberation with Samveganam (intensely), the realization of moksha is near.

Now the question which naturally arises from this proposition is, where does the concept of moksha fit into the philosophy of Yoga? Yoga philosophy similar to Samkhya believes that spiritual ignorance or ajnana or avidya is the cause of all suffering (dukkha) and anger (krodha), and pays special attention to the cultivation of what Chip Hartranft, the English translator of Yoga-sutra calls “wholesome though.” The text itself does not mention the word moksha, instead, it uses apavarga (emancipation or liberation), from the wheel of samsara (cycle of rebirth).

For the discernment of mithya and bhranti (false perception) from jnana (knowledge), the Samkhya and the Yoga philosophy employ what is known as Pramana or proof. For a proposition in both schools to be valid, the proposition needs to hold against three of the six pramanas proposed by the Pramana theory: Pratyakṣa (direct sensory perception), Anumāna (inference), and Śabda (testimony). In relation to direct perception and inference, Patanjali writes in Samâdhi-pâdah, sutra 7:

||pratyakshanumanagamah-pramanni||

meaning, the right perception stems from direct observation, the inference drawn from an observation or the testimony of others.

He further elaborates that viparayayo mithyagyanam atad rupa pratishtham, perversive knowledge or impaired cognition contaminates the cognitive abilities of an individual by casting a shadow on the real cognition and urging the individual towards Andha tamisra (blind stupidity). And that is why the filtering of information through these three pramanas should be carried out so that mithyagyanam (false perception) and avidya can be avoided.

The Samkhya philosophy discusses three kinds of Gunas or attributes: sattva, rajas, and tamas. The gunas are a key concept in nearly all Hindu philosophies, and it is through the composition and interplay of the Guans that the character of an individual is decided. So, for instance, if there is an imbalance of gunas, with Rajas overpowering the other two gunas, the individual tends to be too egotistical and displays a proclivity towards self-centredness.

In Yoga Sutra’s Vibhuti Pada, which deals with Siddhis, sutra 56 mentions:

||sattva-purusayoh suddhi-sâmye kaivalyam||

Sattva here refers to the clarity or luminosity of thoughts, and Patanjali writes that, once the prakriti, or the essence, has become as pure and luminous as the purusha, and the two elements can be superimposed on each other, then the absoluteness (kaivalyam) has been attained. The two philosophies also talk about striking a balance between the three gunas, so that no one Guna subsumes the other two. The balance facilitates udita (clarity) and spiritual growth. Yoga also aims to promote the development of sattva while curbing tamas.

The modern understanding of Yoga has been straying further away from its original definition and has frozen within the narrow walls of pranayama and asana, with the other aspects of Ashtanga Yoga receding into non-existence, primarily because of their philosophical complexity. Concepts like Pratyahara (withdrawal of senses) and Dharana(concentration and conceptualization of an idea), which require intense philosophical deliberation are often side-stepped, in favour of more marketable and easily packaged notions of pranayama and asana. The term Yoga which encapsulates an entire branch of philosophy is being paraded as a sum of two elements. Samkhya has also been absent from philosophical discussion for a while, again because of its philosophical depth, and has all but disappeared from the general discourse on philosophy. These philosophies, along with the other Eastern philosophies, that have a general tendency to look inward for meaning, by withdrawing the senses and disengaging the senses from reality, have found it hard to contest with the Western philosophies (in a capitalistic society), which urge the subject to look outward, for meaning, for pleasure, and happiness.