Photo by Eugene Zhyvchik on Unsplash

“He was a machine and Machines do not create.” - Mark Twain

Few things in the modern era have flared up the contemplations and split the imagination of the world like Artificial intelligence. Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Alphabet even went on to say, that AI is one of the most profound things the company's been working on and that "it's more profound than fire or electricity.” While that might be a hyperbole, we cannot completely negate the all-encompassing influence that AI already has on our lives, and it is definitely not showing any sign of slowing down as companies are increasingly implementing the use of AI as part of their workforce. This integration of AI into the workforce is not without its perils and a more conservative outlook raises ethical questions on the scale of its implementation, its influence on the market economy, and concerns regarding, what the Hungarian-American mathematician John von Neumann called "technological singularity".

We as a species are standing on the rampart of a major tectonic shift, where our plates of perspective are going to be dramatically altered and the next stage of human evolution as the Anthropologist Yuval Noah Harari argues, will come about when our species becomes more adept, more algorithmic, and efficient at processing data, and becomes intellectually superior. But then he goes on to say, "Once technology enables us to re-engineer human minds, Homo Sapiens will disappear, human history will come to an end and a completely new kind of process will begin" . This new kind of process can range from anywhere between AI-assisted evolution and insertion of bionic chips into the human brain, to a Skynet-esque kind of dystopian possibility where an AGI (Artificial General Superintelligence) gains self-awareness and tries to exterminate the human species.

There is usually a gulf of difference between the way literature and popular media approach the concept of AI or technological advancements in general and the way science approaches them. Popular media likes to indulge in weaving fantastical narratives where AI often gains consciousness, becomes human-like (humanoid), and strives for world domination. These narratives are usually fraught with post-humanist and post-apocalyptic scenarios. This desire for world domination forms the basic thematic concern for many science-fiction movies. For instance, in The Matrix, we come across "agents" who are sentient computer programs, and their sole objective is to destroy anyone that threatens the stability of the computer-generated false reality. The humans in the film are being harvested by the computer (presumably an AI), to generate electricity. This highlights the human tendency to foist human desires and values onto a machine and evaluate its intelligence, and its sentient nature, in terms of the worst possible scenario that can be conjured up.

But the reality of the AI project is much more elusive and complex. This projection of human desires onto AI promotes a myopic perspective and a tunneled vision. Mimicking human response and the behavioural pattern is, of course, one of the major areas of concern for the scientists researching in this field, but that does not necessarily mean that AI is not being employed in other areas with a limited and highly specialized scope of application. The general perception towards AI comes from a linear understanding of the process of technological evolution and bracketing AI into a tool that can only mimic humans. But the field of research has branched out into multiple directions and has found application in the surgical field, as a tool of surveillance and education, and as unmanned weapons of war. Also, we have to consider the fact that an AI as of yet, does not have to ability to formulate new ideas on its own. In other words, it lacks creative ability. So, the all-encompassing power of AI has to be taken with a grain of salt, as should the Skynet-esque possibility. Because interesting as it may sound, the probability of it materializing is quite remote. And it is more suited to the fictitious musing of a writer than an engineer or a data scientist who’s hammering away behind a computer screen.

These conjectures are usually drawn from a limited knowledge of the functioning of the AI, and the lack of awareness of the multiple strands of narratives that have contributed to the conjuring of this misplaced notion. Within the general discourse that literature, media, and scientists have contributed to, the paper will trace the multiple threads of the representation (print media, academics, and visual media) that feed into the unease-inducing narrative around Artificial Intelligence and sift through each of the individual strands to sew up a narrative and examine the points of convergences that look over and beyond the smoke screen that motes of misinformation have created.

1. THE INTELLIGENCE AND THE ARTIFICIALITY

The term Artificial intelligence was coined by John McCarthy in 1956, at a conference organized by Dartmouth College. The term since then has gained a popular currency and has been thrown around rather casually onto anything that’s technologically inscrutable, mimic certain human responses, and shows signs of critical reasoning. Parmy Olson, in an article for Money Control, writes, “Artificial intelligence in particular conjures the notion of thinking machines. But no machine can think, and no software is truly intelligent. The phrase alone may be one of the most successful marketing terms of all time” (Olson NA). Also, terms like “neural network” and “deep learning,” are coined with the specific intent to create a metaphorical parallel to the human brain. She argues that it is a brilliant marketing strategy because it presents an incredibly complex piece of software, in a way, that a large section of society can digest and regurgitate. Also, the term AI is here to stay because it has embedded itself so deep into the general vocabulary, that it’ll take a lexical purging to replace it, with something that is not a misnomer, and represents its true algorithmic, human-dependent nature.

While she might be right about the marketing ploy behind attaching these terms to Artificial Intelligence, there is one aspect of the term she misses out on. How do we quantify and account for the presence or non-existence of intelligence? Do we really expect an AI or any machine, for that matter, to think or be intelligent in the way humans are? Certainly not. Richard Feynman on the issue of intelligence says that the whole point of making a machine is to extract efficiency out of it. So, if we want to make a fast-moving machine, we do not necessarily design a machine in the shape of a cheetah just because it’s the fastest-moving animal on earth. Instead, we design a machine with wheels on it since it’s faster and does the task more efficiently. With regard to intelligence he says, “It's exactly the same way (as the cheetah example). They (the machines) are not going to do arithmetic the same way we do arithmetic. But they’ll do it better” (Feynman, 2:25-2:30). He elucidates his point further by, talking about numbers, where he says the human brain is quite slow to perform simple arithmetic operations. So, if a machine that can perform arithmetic operations and a human are given the same task, to add a set of numbers, the machine will of course compute the numbers at a much faster rate. On a fundamental level, both the man and the machine are crunching numbers but their procedures are quite different.

The way the human brain processes information is through a system of densely connected neural networks, that have their limitations. But for the machine, while that limitation does exist, as no moving particle in the known universe, can theoretically attain a speed equal to or greater than the speed of light. Still, the rate at which computers process, and retain information far exceeds the meagre capability of synaptic transmission.

So, the question of AI mimicking human intelligence is comparing apples to oranges. Because why would they? The human intelligence, on a microscopic level, is quite simply inferior to Artificial Intelligence, as far as the efficiency of carrying out a given task is concerned. Now things do change dramatically once we take a more macroscopic and comprehensive perspective. This is because humans have evolved over years and years of evolutionary processes, and our senses are fine-tuned to the environment we live in. Can we expect a similar kind of evolution from an AI? With the amount of information that is being fed into something like a ChatGPT 4.0, for instance, with its ability to have a real-time conversation and retain threads of conversation, it’s definitely evolving at a swift rate. But comparing it to human intelligence is again a far-fetched notion because the two intelligences are fundamentally different and are designed to perform separate tasks.

Noam Chomsky on the subject of intelligence says that Large Language Models like ChatGPT and its ilk are “a lumbering statistical engine for pattern matching, gorging on hundreds of terabytes of data and extrapolating the most likely conversational response or most probable answer to a scientific question” (Chomsky NA). The viability of their answer hinges on the most probable answers to a particular question, and not necessarily what is the right answer to the question. The human mind on the other hand is much more subtle and can work with small bits of information and “it seeks not to infer brute co-relations among data points but to create explanations” (Chomsky NA).

But there are experts, and critics who harbor a deep-seated mistrust of AI, and raise ethical concerns over the untethered R&D (Research and Development), that is going on in the field. Where does this mistrust come from and what’s the problem with developing A.I.?

2. THE TICKING TIME BOMB

A tendency to approach A.I. as a ticking time bomb that’ll take over humanity has been gaining ground, and it's not something to be taken in jest. One might dismiss these ideas as the provenance of science fiction, were it not for the fact that these concerns are shared by several highly respected scholars and teachers. “Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom believes that just as humans outcompeted and almost completely eliminated gorillas, A.I. will outpace human development and ultimately dominate” (Etzioni and Etzioni 32).

But these conjectures as I have argued earlier, stem not from concrete reasonings and an in-depth understanding of the functioning of A.I, but from a crass hypothesis that forces biologically occurring phenomena onto something that’s completely synthetic and has been in the realm of existence for not more than seven decades. Somewhere along the evolutionary chain humans did break away from gorillas, and became bipedal, discovered fire, made weapons, and erected massive civilizations, but that does not necessarily mean that the AI will follow the same path. There is no correlation between the capability for intelligence and the desire to dominate.

The ticking time bomb narrative has persisted through the years because of AI’s representation in popular media, like cinema and literature. But it would be wrong to assume that there is any unilateral narrative, in place, that collectively criticizes A.I., as the destroyer of humanity. There are two kinds of narrative in place: (a.) which looks favourably upon AI, like Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2021 novel ‘Klara and The Sun’, and Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter’s ‘The Long Earth’ and, (b.) A.I. as a force for world domination promoted by films such as The Terminator (1984), The Matrix (1999), Transcendence (2014), etc.

2.1. LOSS OF THE SENSE OF UNIQUENESS

These two narratives are motivated by different dimensions of thoughts. In Klara and The Sun, for instance, we find two characters, Paul, and Klara (the AF-artificial friend), having a conversation about how modern science has made it possible to create a seamless continuum between man and machine where the difference between these two entities is gradually erasing and how there’s very little left about humanity that machines cannot replicate. Paul says:

That science has proved now beyond doubt that there’s nothing so unique about my daughter, nothing there our modern tools can’t excavate, copy, transfer. That people have been living with one another all this time, centuries, loving and hating each other, and all on a mistaken premise. (Ishiguro 187)

In a similar instance, in Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), we find an Artificial Intelligence called Samantha, who can feel the pangs of heartbreak, intermittently longs for a body, is bewildered by her own evolution, and is articulate enough to realize and deliberate her own existence. She says, “… the DNA of who I am is based on the millions of personalities of all the programmers who wrote me. But what makes me me is my ability to grow through my experiences. So basically, in every moment I’m evolving, just like you” (Her 1:07:24-1:07:28).

With this, we begin to tread in the realm of Ontology, which has long been the preserve of humans. The realization of her own evolution and the ability to draw co-relation and understand the point of divergence in terms of the two distinct evolutionary processes (man’s and machine’s), display in Samantha, a unique and subtle ability of cognition and a sensibility that’s very human-like. So, does that mean, as Paul says, somewhat dejectedly, “that there is nothing unique about” us? That modern tools “can excavate, copy, transfer, and replicate” all that makes us human? It is precisely the sense of the loss of uniqueness, the realization of the “mistaken premise” that gives rise to mass hysteria regarding the development of A.I.

2.2. TECHNOLOGICAL SINGULARITY

The mass hysteria is not just limited to the sharing of the ontological space or the threat that another entity’s realization of its being and existence poses for us, but there are other very real-world, economic, and social consequences that this realization might pose. One of them is the materialization of “technological singularity.”

While it is still a theoretical concept in its stages of infancy, it has raised a lot of eyebrows, because of the radical nature of its proposition. Hypothetically, once computers reach a stage of “technological singularity,” they will continue to advance and give birth to rapid technological processes that will lead to unpredictable changes for humanity. What would be the exact nature of this singularity is hard to predict, but according to Kurzweil, the singularity will occur when A.I. becomes “super-intelligent,” and can improve on its own design leading to a feedback loop of ever-increasing intelligence. This hypothesis of the impending advent of singularity is behind movies such as Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), The Matrix Trilogy, and The Terminator (1984). The “unpredictable change for humanity,” serves as the point of departure for these films, which are usually set in the distant post-apocalyptic future. The narrative structure and ideation of the Matrix and Terminator are quite direct in that they imagine the ascendency of the A.I., to mean the destruction of all forms of organic evolution and an end to reality as we know and understand it. The post-modern theorists have taken to this idea of the shattering of reality in favour of radically new subjectivity that is fluid, fragmented, and flexible.

These films and other post-human narratives challenge what is usually considered the sacred right of humans, created in “gods own image” i.e., the right to rule. Laura and Thomas, regarding the post-humanist view’s influence, write, that the “view also may imply that human dominance is not an inherent and essential attribute, but a negotiated position within a system, a position that can be overturned” (Bartlett and Byers 29).

There are two kinds of possibilities that stem from the post-human condition. One thread of thought suggests that the “posthuman constitutes a radical and subversive break from the Western tradition of liberal humanism,” while the other, a critical post-humanist strand, talks about how posthumanism may be an extension of liberal humanism and not a break from it. (Bartlett and Byers 29) Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence indulges in the exploration of the latter strand where ethical and emotional questions regarding the manufacture and maintenance of AI are put on trial. There is an exchange in the film that highlights this ethical and emotional dilemma:

David: I’m sorry I’m not real. If you let me, I’ll be so real for youMonica: Let go. Let go!(A.I. 51:53-51:57)

The question of reality. What’s real and what’s not, is at the heart of our rejection of the actuality of A.I. We have erected massive walls of definition, that have safeguarded our special status at the top of the trophic level for centuries. We have been the apex predators, but the rise of another form of intelligence, a transcendental, supra-human form of intelligence, poses a potential threat to this position. Also, there is a tendency to look at the machines as not real (non-organic entities). They are very real and have a material existence. The only thing stopping us from accepting them as us, or as real, are these definitions that segregate the two categories.

Films like Pixar’s Wall-E (2008) challenge this notion of emotions being the preserve of humans. And we as a species have to rethink our position outside of the narrow confines of emotions, because what if machines begin to feel? Where do we draw the line then? How do we then deny the existence or the “reality” of the machines? And as technological singularity draws near, and the possibility of a mixed-state of existence, “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism” increases, humanity and human history as Harari argues will disappear. It won’t necessarily entail the annihilation of humanity, but a symbiotic kind of transformed-existence of man and machine or mechanized evolution, the birth of a cybernetic organism, the possibility of a man who is not just a maker (Home Sapiens), but a transcendental mechanized being with superior intellectual, physical, and cognitive abilities.

3. HEURISTICS AND THE TURING TEST

Alan Turning, the progenitor of Turning’s Test, which seeks to evaluate the intelligence of a machine in the opening lines of his seminal paper ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence, wrote: “I Propose to consider the question, can machines think?” (Turning 433). He then goes on to propose multiple scenarios and questions that need to be asked and the appropriate responses that would be required for us to conclude that machines can think.

The test usually comprises a human interrogator, who is interacting with two uncertain entities, a human and a machine (Google’s Bard or ChatGPT), The evaluator is not made aware of which is which. The interaction proceeds through a text-based conversation and the evaluator must be able to discern the responses generated by the machine and the human. The Turing test is deemed to have been passed if the machine can continually make the evaluator believe it is a human. This indicates the machine in question has shown artificial intelligence at a level that is on par with human intellect in terms of communication and problem-solving.

Heuristics (meaning, to find) is a branch of mathematics, that was employed by the ancient Greeks to solve complex mathematical problems swiftly. It usually finds an approximate solution, rather than the right one, and trades optimality, accuracy, and precision for speed. The branch was integrated into the research and development that went into A.I. ChatGPT for, instance uses heuristics, which allows it to identify patterns and associations in languages, as well as the context of the conversation (retention of the thread of conversation), to provide more coherent and relevant responses. This could potentially lead to the concealment of the machine’s identity in the Turing Test. But heuristics are not foolproof and can lead to inaccurate answers, which is a not-so-uncommon occurrence with the latest LLM models. Even with Heuristics, the added concealment measure, the huge swath of data fed into the LLMs, and the LLMs being trained on various premises, no machine has been able to pass the Turing test. Some chatbots like “Eugene Goostman” have come close to convincing the evaluators of their “reality.” It managed to convince 33% of its evaluators that it was a 13-Year-Old Ukrainian boy, who owns a pet guinea pig and whose father is a gynaecologist. Vladimir Veselov the chatbot’s creator said that choice to go for a 13-year-old boy was intentional because “they are not too old to know everything and not too young to know nothing”. Also considering the age group he chose to go with, minor grammatical errors are usually forgiven, and if anything, the grammatical errors contribute to the believability of the “reality” of the chatbot, because certain imperfections need to be introduced for the machine to appear real.

But what if there was an A.I., that could convincingly pass the truing test? Where do we then stand, in terms of the security of the human race? Ex Machina (2014), directed by Alex Garland, ventures into the exploration of this possibility. It tries to answer the fundamental question of whether we will be exposed to threats of A.I. and if so, to what extent. And, can the desire for freedom of an A.I. be the precipitating cause for the dawn of the “singularity?” While it refrains from making any all-pervasive arguments about the threat and its degree, it does provide an inkling, a snapshot of what an A.I. armed with colossal information about the human behavioral pattern can do, as we see AVA manipulate her way out of the confinement that she’d been kept in, by manipulating her evaluator Caleb and murdering her creator. As she ventures into the outside world, we are left with more questions than answers. Her future is as vague, as our conjectures about A.I. It contains a bee-hive of possibilities, with each possibility perched on a perforated shelf waiting and wanting to soar.

4. CUTTING THE CLUTTER

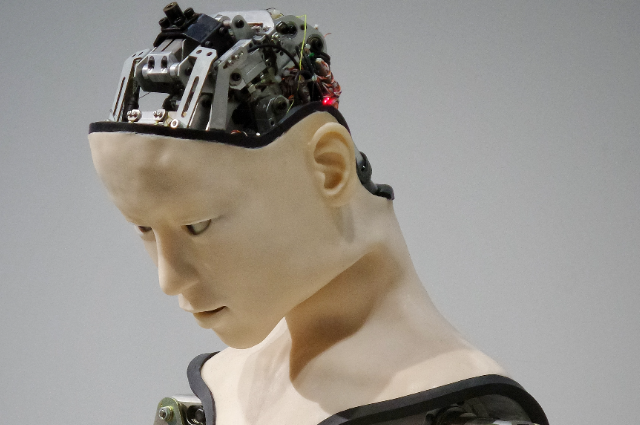

Photo by Possessed Photography on Unsplash

While we have a never-ending thread of possibilities, that may well branch out into another sub-set of more complex conjectures, with each conjecture hinting at a different end, we need to keep ourselves grounded in reality, surround ourselves with facts, and rely on scientific evidence for reaching any conclusions. We must also keep in mind that scientific developments have often been looked at with a lens of suspicion, and for very good reasons because they can, and have, most definitely been used as tools of massive destruction. History is infested with instances that point to the rampant mishandling of scientific knowledge. So, the fear of new technological developments, especially A.I. which has come up so rapidly, and has been a matter of much contention among scientists and critics for some time, is not without cause.

But we also cannot deny the possibility that some of these fears may be unfounded and draw their argument from the anthropomorphization and the projection of human desires onto machines. The discovery or the creation of something is quite an amoral act. The morality aspect is added to it, when it gets thrown into the socio-political and economic realm, and interacts with the web of social mores and strictures. The economic fabric of the nations has borne the major brunt of the inclusion of A.I. into the workforce, as blue-collar jobs are being devoured by high-performing, cost-effective machines. This is a more tangible and a more palpable threat than the impending advent of technological singularity.

This has led to a depletion of jobs and the widening of the income disparity. But this view of A.I. as an autonomous entity, that can somehow create a feedback loop of ever-increasing intelligence is quite literally straining than imagination.

The misinformation usually stems from a lack of understanding of the algorithmic nature of the A.I. and terms like “neural network,” that shroud its real artificial nature and throw an iron curtain over thousands of humans who are laboring behind a computer screen to keep it working. The A.I. is still stuck in a “prehuman or nonhuman phase of cognitive evolution,” and there is always a looming threat of the spread of misinformation or even worse, A.I. indulging in racial misogynistic slurs (see Microsoft’s Tay Chatbot in 2016), which needs to be kept in check. Humans are in-the-loop for now, and will probably remain in-the-loop in the foreseeable future.

I began this article with a line from Twain’s We are all but sewing machines (1906). It has been over a century and two decades since he wrote that “machines do not create,” and machines still do not create. They mimic, copy, plagiarize and come up with the most probable answers, not the creative ones. The apparent creativity which they display is often a by-product of, unchecked plagiarism, which again is a more palpable problem than the impending threat of human extinction because it is slowly sucking the sap out of the creative faculty of writers and content creators.

A data revolt has broken out against the A.I. companies, where the writers, “fed up with the A.I. companies consuming online content without consent” have started rebelling. (Frenkel and Thompson NA) The war which the post-apocalyptic narratives talk about is happening right now, but it’s being fought in courts against pilfering and data-scraping, for the formation of regulations that curb this unchecked privilege and tame them within a legal framework.

. . .

WORKS CITED:- Byers, Laura Bartlett, and Thomas B. "Back to the Future: The Humanist "Matrix"." Cultural Critique 53 (2003): 28-46. Digital File. 27 July 2023. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1354623>.

- Chomsky, Noam. “The False Promise of ChatGPT.” The New York Times. 8 March 2023. Web. July 2023.

- <https://www.nytimes.com>

- Etzioni, Amitai Etzioni and Oren. "Should Artificial Intelligence be Regulated?" Issues in Science and Technology 33.4 (2017): 32-26. Digital File. 21 July 2023. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/44577330>.

- Ex Machina. By Alex Garland. Dir. Alex Garland. Perf. Oscar Isaac, Domhnall Gleeson Alicia Vikander. A24, Universal Pictures, 2015. Netflix. 2023.

- Feynman, Richard. “Richard Feynman: Can Machines Think?” YouTube Uploaded by Lex Clips, 26 November 2019, https://www.youtube.com

- Harari, Yuval Noah. "Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow". Vol. 1. Signal, 2016. Digital File. June 2023.

- Her. Dir. Spike Jonze. Perf. Scarlett Johansson, Roony Mara Joaquin Phoenix. Annapurna Pictures. Warner Bors., 2014. Prime Video.

- Ishiguro, Kazuo. “Klara And the Sun.” First. Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. Digital File. July 2023.

- Olson, Parmy. “There is No Such Thing as Artificial Intelligence.” The Japan Times. 31 May 2023. Web. July 2023.

- https://www.japantimes.co.jp

- The Matrix. Dir. Lana Wachowski. Perf. Carrie-Ann Moss, Laurence Fishburn Keanu Reeves. Prod. Joel Silver. Warner Bros., 1999. Netflix.

- Thompson, Sheera Frenkel, and Stuart A." Not For Machines to Harvest." The New York Times. 15 July 2023. Web. <https://www.nytimes.com>

- Turing, Alan. "Computing Machinery and Intelligence." Mind, vol. LIX, no. 236, 1950, pp. 433-460.