Source: imdb.com

What is a woman? What is an Indian Woman? What constitutes the femininity of a woman? Is femininity exclusively anchored in one biological sex like a concrete set of data that is unchangeable and timeless? Is it a cultural construct that has been engineered specifically to foist onto women all the negative qualities that the men (the patriarch(s)) wish to deny in themselves? Has it been genetically encoded into the ‘x’ chromosome that, somehow having two of them suddenly ordains the biological females to behave in a feminine manner? Or is there a hegemonic, performative practice at play that thrives on creating differences between the two biological sexes by attributing contrasting acts and actions (dress, mannerism, physique, etc.) that separate a “man” from a “woman”?

A constant conflict for power informs this quest to define women and femininity, what women should be like, and what is culturally appropriate for them to wear, speak, or eat. The feminine is usually posited against the masculine, and these two notions are enacted regularly in our daily lives, through popular media like theatre, literature, and more recently in the Indian television serials, which are notorious for their depiction of women as meek, feeble, fragile, sacrificing, and subservient. The enactment and the regular re-enactment of these notions accords a semblance of naturality to gender and the repetition of these “gendered acts create the illusion of a stable gender identity” and the unchanging notion of femininity.

An alternative to this natural, timeless, and traditional representation of woman appears in Judith Butler’s ‘Gender Trouble’ (1990) where she posits that “being born male or female does not determine behaviour. Instead, people learn to behave in particular ways to fit into society. The idea of gender is an act or performance.” Butler deconstructed the notion of gender as an immovable fixity and brought out the hidden cultural, and patriarchal ideas that bolster and supply the maintenance of this notion.

Mrinal Pandey writes “Women in the accepted sense of the term in India, have all been created not born”. The Parsi theatre has been instrumental in defining and concretizing the notion of the ‘Aadarsh Bhartiya Naari’ (ideal Indian Woman). She is usually a sari-clad woman, a loving wife, and a responsible homemaker who never goes against the wishes of the family and cares for the children without cherishing any desire for her well-being. The representation of women in Bollywood and popular Indian literature also draws from the same notion that the Parsi theatre contrived into existence, nourished, and naturalized through repetition. This deliberate contrivance has had far-reaching consequences. It has imprinted itself so deep into the modern Indian conscience and has so subtly concealed its existential roots that it appears almost ancient.

The forgery of timelessness and tradition grants a cultural legitimization to patriarchal men, who occupy most of the cultural spaces, to yoke female and femininity together, and position one as a natural consequence of the other. If one is a female, one ought to be feminine. And, if someone breaks out of this neatly drawn classification(hijras) they are ostracized and sometimes even persecuted by society.

In the subcontinent, particularly within the Hindu-cultural system, it is not enough to be feminine one must perform all the associated activities attached to femininity that align with the dominant Hindu view of women, as well. This dominant view (of the Bhartiya Nari) is not millenniums old but has been birthed into existence fairly recently through the Parsi theatre. The Parsi theatre through performances disseminated certain notions of femininity that have been sustained, absorbed, replicated, and endorsed (through theatre and cinema) as authentic and truly Indian in essence. These notions need to be deconstructed and seen for what they are theatrical performances.

THEATRE AND GENDER PERFORMATIVITY

Theatre before the arrival of the cinema was an influential medium in constructing and influencing public opinion. It was a significant site for gender formation. It could alter the fabric of social reality and played a major role in stabilizing the hero-normative nature of gender, while simultaneously building the notion of femininity and masculinity.

Butler writes, “Gender is in no way a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts proceed; rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time-an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts”. There is a complex web of interconnectedness that underlines the relationship between theatre, gender performativity, and femininity. Theatre played a major role in shaping, contributing, and institutionalizing this stylized repetition of act. It created a hegemonic notion of femininity across cultural and geographical spaces.

The actions transitioned from a state of high- artificiality to guileless naturality through the repetition of acts on stage, about what femininity should be like. So much so, that there was a need in society, for women to perform or replicate these acts in their daily lives as well. Theatre essentially served as a didactic medium. The Parsi theatre was not very different from modern cinema in terms of its influence, because there is always a two-way relationship between the audience and the film or plays itself. So, we find instances of art imitating life, as much as life imitating art. It is the latter part that concerns this debate about female and gender performativity. There, we see the struggle for control over the female body transpire.

source: imdb.com

We will look at a few instances of how theatre influenced gender and its associated performances, and try to ascertain to what degree if any they influenced the stabilization of gender. If we take the case of the Chinese theatre art of spoken drama called the huaju we observe that “gender-appropriate casting only became a standard practice in the 1920s when modern scientific discourse…made cross-gender dressing seem an unreasonable choice in huaju” (Liu 35). The Chinese took this concept of cross-dressing from Japan’s first modern theatre shinpa where male actors known as onnagata performed female roles. The use of Female impersonators was not unique to the Orient. In England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603), which was marked by a period of high dramatic activity, certain things were restricted by the Queen’s law. “One of the main particular features of that time was the fact that the women’s roles were played by young handsome men”. Young men had to play these roles because there was no other alternative and, also because of the demand for these young men in certain theatrical spaces.

Mrinal Pandey, a theatre historian mentions the curious case of master Wasi of Lahore. She writes, “If stage legend is to be believed, some fans of Wasi were so overcome by emotions that they ripped their sleeves and fell in a dead faint in the aisles” (Pandey 1646). Wasi remained active on stage from 1915 to 1935 and died of various kinds of alcohol and drug addictions. This overwhelming response to a young boy, playing the role of a woman tells us something about the theatre-going audiences at large. That they would much rather have a man perform the role of a woman than a woman, and that theatre was a space that was regulated by men. It also catered to a largely male audience. What Wasi performed could be understood in relation to the stylized repetition of acts in time, which was approved by the largely male audience as feminine even though he was a man performing the role of a woman. So, femininity has nothing to do with females. It is performed, and through mass approval (largely patriarchal) is absorbed, and in time naturalized within society. We observe similar instances, where female impersonators like Master Champalal, Jaishankar Sundari, and Bal Gangadhar enjoyed huge success in the Parsi theatre performing female characters.

What was this Parsi theatre and how was it instrumental in institutionalizing the idea of the Adarsh Bhartiya Nari? What did it mean when the public was much more willing to encounter the body of a female impersonator on stage rather than the body of a woman playing a woman? These choices tell us something about the period, they tell us something about society in flux and the kinds of negotiations that we are constantly engaging in, in the performativity of gender roles.

THE PARSI THEATRE:

Anna Hari Salunke, who performed in the Parsi theatre and played a double role of both Rama and Sita in D.G. Phalke's 'Lanka Dahan'(1917)

source: www.wikipedia.org

The Parsi theatre enjoyed its heyday from 1853 to 1931. The first recorded instance of an Urdu play performed in the Parsi theatre was ‘Sone Ke Mul Ki Khurshid,’ (1871) written by a Parsi playwright who wrote under the pen name ‘Aaram.’ According to Dr. Harmony Singaporia the Parsi theatre was a secular space, which saw the representation of multiple Indian cultures and was in no way a site for the proliferation of communal values. Despite the use of the term Parsi, which might be slightly misleading, the theatre did not endorse any communal values and was called so, because the first theatre houses and performance companies were financed and owned by Parsi communities, in and around the Bombay presidency. It was never exclusively the preserve of any religious or linguistic group.

Tracing the contours of the Parsi theatre from infancy to maturity and its eventual demise takes us through multiple avenues of languages, cultures, and its failure to keep up with modern social mores and technological developments. The theatre’s primary languages were Gujarati, Urdu, and Hindustani. The Parsi theatre began with the adaptation of Shakespearean dramas, before moving on to writing and adopting stories from Persian mythology like the story of ‘Rustam and Sohrab’ and Shahnama. It also drew inspiration from the Hindu epics and staged multiple sections from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. It eventually stepped out of this and moved into the realm of ‘the romantic social drama’ the influence of which is still observable in Hindi soap operas and telenovelas.

The gradual erosion in the theatre’s popularity began with the end of the silent cinema and the birth of the talkie. The release of Alam Ara in 1931 which was directed by Ardeshir Irani who was a Parsi as well, was a turning point in the Indian entertainment industry because it weeded out the possibility of the revival of Parsi theatre. It represented an outdated mode of artistic expression that was no longer relevant. The only possible edge that the Parsi theatre had over cinema before 1931 was that the characters on the stage were not silent, and had the power of oratory. Once the difference was eliminated, the Parsi theatre could not reinvent its identity. Several writers who wrote for the theatre also moved to the film industry because it had a larger audience and was financially more lucrative as well.

Contrary to the argument that performing women were unavailable, the record shows that the Parsi theatre employed both female impersonators and actresses for a considerable duration. In a sense, they competed against each other, and companies and the public made choices about whom they wished to represent women on stage-men or women. - Katheryn Hansen

The other important change that accompanied the death of the Parsi theatre and the ascendancy of the Cinema was the use of Female actors instead of female impersonators. The introduction of cinema almost necessitated that change. The Parsi theatre borrowed a structural element from the western theatre called the proscenium. It added grandeur to the stage and established distance between the actor and the audience, which made impersonation possible by creating an illusion of reality. The distance made it difficult to distinguish between an actress and an impersonator. The removal of the distance with the introduction of the camera used to shoot films eliminated the possibility of female impersonators acting out the role of women, and the competition Katherine Hansen mentions was all but over. The era of female impersonators had come to an end. But that does not mean that the influence they had on the mass conscience, the part they played in shaping the discourse around femininity in India has receded or waned. It continues to affect us and resurfaces time and again because the “female impersonators structured the space into which the female performers were to insert themselves” (Hansen 127: 1999) and that performance through constant re-enactment, first on the stage and then in cinema, has percolated into the society and has become inseparable and synonymous to the ‘Ideal Indian Woman.’ This construction of women as I have mentioned earlier appears timeless but is only part of a tradition that is one and a half centuries old.

PERFORMANCE OF GENDER IN THE PARSI THEATRE

A still from 'Sound of Heaven: The Story of Bal Gandharva(2015)

source: imdb.com

There are two broad ideas that we must understand before we embark on this journey of unspooling the many layers of thread that supply the Indian women with their supposed Indianness. Kathryn Hansen talks about “the once spurned” female performer who has been embraced as a “ubiquitous emblem of Indian national culture” (Hansen 127: 1999). This female performer’s femininity which was embraced and endorsed primarily by the nationalists was in fact a performance that had its origins in the acts of the Parsi female impersonators. This notion of the ubiquitous Indian woman has survived and can also be seen in the representation of women in contemporary cinema. Mrinal Pandey argues that there is a direct correlation between the young-baby-faced Parsi theatre players of female roles and the present-day portrayal of women in Hindi cinema because “while the ‘femininity’ on display may well be different in scope and degree, it is not different in kind”.

The other point worth noting is the theatre’s relation to popular Hindu mythology. The mythological female characters like “Sita, Draupadi, Subhadra, Damayanti, and other heroines from the epics have been long celebrated in the visual and verbal arts and rightly credited with establishing gender roles for women in society”. The representation of women in mythology through female impersonators played an important role in establishing the notion of the Bhartiya Nari, which they presented as something that was part of an unbroken and singular tradition across time in Hindu society. For instance, in Dadasaheb Phalke’s Lanka Dahan (1917), which was an adaptation of Ramayana, Anna Hari Salunke a female-impersonator actor played the role of both Ram and Sita. In Vishwamitra Menaka (1919), directed by D.D Dabke, KP Bhave played the role of the heroine. While talking about the representation of female mythological characters we need to be conscious of the choices for the role models that the nationalist movement promoted. It was always Sita, Savitri, Damyanti, Shakuntala, and never Supranakha. The politics of representation, in the characters being portrayed, becomes obvious and the vision of the kind of womanliness that was being constructed emerges clearly.

Occupying the theatrical space as a female actor or a female impersonator meant a lot more than acting and carried within it the power to shape and formulate discourses. “Young men of pleasing figure and superlative voice were sought out to play women’s roles.”. Talking about the broader cultural relevance of performativity Butler mentions, “The act that gender is, the act that embodied agents are in as much as they actively and dramatically embody and indeed wear certain cultural significations is not one’s act alone.” This hints at the construction of gender as a shared activity, in which a society partakes not as individuals but as a collective and turns femininity into an object of visual consumption.

Indian women were depicted first by Indian men and then by foreign women on the national stage and early cinema screens, both of which, at the level of image seem to have provided greater spectatorial pleasure than the categories ‘Indian’ and ‘woman’ together could have afforded at the time

-Harmony Singaporia

Also, talking about the cultural significations that one must wear, to be feminine in India (sari, Sati-Savitri, modesty, marriageability, silence), they come from the tradition of female impersonator(s) (mentioned before) and early female actresses like Miss Mary Fenton, Miss Gauhar, or Miss Umda Jan. These were among the first female actresses who broke through the rigidities of the stigmatized social structure in which “women from good families dared not come into the ‘mardaan khaas’ (Spacious living rooms for men) of their own houses” (Pande 1646). But these actresses were rarely seen as ‘respectable working women’ and their hair, their jewellery, their fair skin, or their sexual availability were sanctioned as the standard denominator of desirability. Pande talks about how the growth of theatre and cinema created a space for women to talk about their issues and nurtured a scope for social change. But, since these actresses, had to insert themselves into the space(repressive) created by the female impersonators, their expressions of femininity were stifled under the weight of tradition and a repressive structure that acted against them and forced them to be feminine. And this is how we come to what became the normative representation of the ‘Bhartiya Nari,’ in literature and popular media.

FEMALE ACTRESSES AND FEMALE IMPERSONATORS

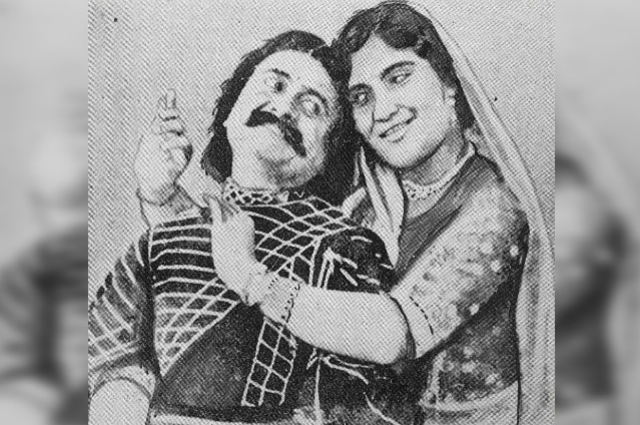

Jaishankar Bhojak/ Sundari( Right) with his arms wrapped around Bapulal Nayak(Left)

source:www.wikipedia.org

Female impersonators held the reins of discourse when it came to creating notions about femininity for a sustained period of time. For instance, we find Master Champalal saying that long silky tresses are a must for being a woman. He goes on to say that as long as a person is playing at being a female, proximity to men should be avoided at all costs. He talks about how female impersonators had to travel in a separate compartment from male actors. They had to stay in seclusion inside their separate tents and not fraternize with the troupe or the audience. Mrinal Pandey recounts how in an interview he mentioned “Meet other men and you risk getting a ‘reputation’”. There were other rather bizarre dietary restrictions they had to follow. The female impersonators were not supposed to indulge themselves in alcohol or eat spicy food because it was believed that they would spoil their complexion. It could blemish their voices and make them manly and ill-tempered. So, the food that was considered good for a woman and the feminine culinary culture at large also developed from here on.

We find similar sentiments being echoed by Bal Gadharva as well. He was a celebrated female impersonator and enjoyed a lot of cultural significance in terms of his influence and contribution towards the construction of certain contemporary notions of femininity. For instance, the style of draping the nine-yard sari in Maharashtra was copied by the women from Bal Gandharva. To ascertain the level of influence which Bal Gandharva and Jaishankar Sundari possessed over the mass conscience we must understand their emblematic importance within the socio-cultural terrain. A story goes that the women of Bombay would be taken to the theatre by the male members of their families (brothers, fathers, or Husbands), to learn how to perform being a woman by watching the body of Bal Gandharva. By watching him perform they learned how to drape a saree most fashionably- elegantly but also modestly. They would learn what kind of blouse or Nathni (nose ring) was in fashion at a given moment by watching the body of Bal Gandharva traverse the stage.

So going to the theatre was meant to be educative for these women, as I have mentioned earlier about the didactic function these actors played. So, the theatre was a space where notions of femininity were perennially reiterated and performed by female impersonators, and women who witnessed the play were then expected to regurgitate their performances.

The question that arises here is, where were the women? What were they doing while perceptions about their gender were being created? The women were systematically kept away, from the whole theatrical set-up. The theatrical companies, the producers, and the directors including the female impersonators were complicit in blocking access to the stage for female performers for a rather significant period. There are documented instances of Bal Ghandharva vehemently opposing women from performing on stage. Kamla Bai Gokhale, one of the first women on the Marathi stage mentions how she “faced fierce opposition from actors who were playing female roles on stage”. Kamla Bai recounts Bal Ghandharva saying that no woman would appear in his stage productions. Some theatrical companies would not hire actresses as a policy. It is said that Shorabji Ogra the stage director at the Victoria Natak Company was firmly against the idea of women playing themselves on stage “and quit the Victoria Natak Company in protest when others insisted on having them”. He later found another theatre company, which did not hire women as a policy until he was managing it.

It is understandable how restrictions on stage for women would benefit the female impersonators. It would benefit them financially and would also mean that they could enjoy more success without the fear of being replaced. And it took a lot of effort to become what society accepted as feminine, so much so that Master Champalal called it a Sadhana(penance). If women were allowed on stage their years of Sadhana would be undone.

But what about the theatre-going audiences? Why were they complicit in the continuation of the act of the willing suspension of disbelief? They could have easily demanded for women to play women. Theatre like all capitalistic institutions is run by the demand and supply curve where the consumer, as the popular phrase goes, is God. Then why did this practice sustain for around three-quarters of a century? Well, the theatre-going audiences supported the practice of keeping women away from the stage. It might seem kinky or bizarre in the contemporary world, where we are used to seeing actresses perform in cinema, but the cultural geography of the 19th-20th CE was different. There are two reasons for this. The first is that women were seen as property, that must be protected and kept within the confines of the house at all costs, the sanctity of which would be tarnished if she appeared on the stage. So, in early Indian cinema, we find either foreign women or dancing women (nautch girls), performing. “Spectators would get to see English memsahebs dancing, or even more provocatively, men and women dancing together”. Women from the upper castes only start to appear on stage and in the cinema once it became a profitable venture. So, money becomes the antidote to all stigmas. The second reason for the audiences promoting female impersonators was because the spectators were fascinated with the notion of a man playing a woman. Because it was counter-intuitive and not something that wasn’t happening all around them. It was unique and its bizarre nature was fascinating. “The desired end of this performance of gender was that the female impersonators appear so ‘natural’ that he could not be distinguished from a real woman.” It is in that fine space between wearing the garb of naturality and being real, that the audiences derived their pleasure. And performing gender was socially acceptable as well because it fell in line with the policy of keeping women indoors, while also watching femininity being played out on stage by female impersonators and later by foreigners.

However, it could not survive the onslaught of time and the ushering in of the cinema allowed women to make their way onto the stage and the tradition of female impersonators gradually receded into non-existence. Though this phase may have been forgotten in light of everything that came after it, the period still remains worthy of consideration because it helps us understand not only how gender roles are created but also the ways in which these performative practices continue to influence our extremely gendered, lived realities.

For this reason alone, the period under study, the turn of the 19th century remains an invaluable and fascinating one. The tradition of female impersonators on the Parsi stage permits us to articulate our notions of womanhood lucidly and explicitly and allows us to remember how gender is performative. Since it is a category that is up for constant negotiation, how certain forms of negotiation over others may allow us to steer it towards a more meaningful and more inclusive direction.

. . .

WORKS CITED:

- Butler, Judith. "Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory." Theatre Journal 40.4 (1998): 519-531. Digital File. March 2023. https://www.jstor.org.

- Hansen, Kathryn. "Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross Dressing in The Parsi Theatre." Theatre Journal 51.2 (1999). Digital File. March 2023<https://www.jstor.org/stable/4407133>.

- Hansen, Kathryn. "Stri Bhumika: Female Impersonators and Actresses on the Parsi Stage." 33.35 (1998): 2291-2300.www.jstor.org

- Liu, Siyuan. "Performing Gender at the Beginning of Modern Chinese Theatre." 53.2 (2009): 35-50. Digital File. March 2023 www.jstor.org

- Pandey, Mrinal. "'Moving Beyond Themselves’: Women in Hindustani Parsi Theatre and Early Hindi Films." 41.17 (2006): 1646-1643. Digital File.<https://www.jstor.org/stable/4407133>.

- Siganporia Harmony, ‘Stylising the Sphere of Femininity: Women Impersonators on the Parsi Stage’ in Reimagining Masculinities: Beyond Masculinist Epistemologies, (Ed.) Frank Karioris and Cassandra Loeser (Inter-Disciplinary Press, Oxford: 2014). Digital File.

- Wilson, Edwin, and Alvin Goldfarb. “Theatre: The Lively Arts. USA: McGraw Hill.” (2011). Digital File.

- Wilson, Lindsay. "Gender Performativity and Objectification." (n.d.): 1-9. Digital File. March 2023 https://scholarworks.gsu.edu