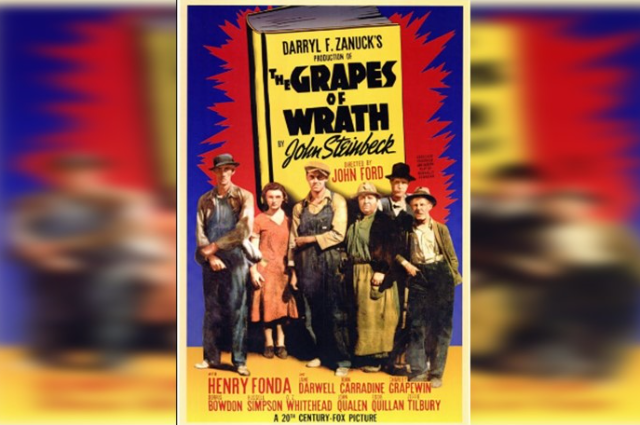

A Still from John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath (1940)/ image by IMDB

Bustling with biblical allusions, and weaving a complex tapestry of the plights of migrant laborers, Grapes of Wrath, arguably considered to be Steinbeck’s magnum opus, is set against the aftermath of the great depression (1929-39) and the dust bowl era (a severe drought that lasted from 1934-39). There is a general proclivity to look at the novel through the lens of its historical accuracy, rather than the human compassion it inspires, the saddening and denigrating state of existence it portrays, the rude awakenings it inspires in the characters, and the powerlessness of the workers it reflects, in the absence of labor-unions and worker solidarity. The rampant exploitation of the “Okies” by corporations, and the state, exacerbate the already precariously hung family structure and the vermined existence of the migrant laborers.

The discriminatory practices are multi-layered and extend well beyond the usage of “Okies.” Through the decades the United States has managed to maintain the polluting influence of racism and has nurtured a racist vocabulary that is replete with verbal dehumanization. In post-war America, we find in Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley in Search of America, the presence of antisemitic and strong anti-black sentiments. Even after a century of the civil war, racial, religious, and regional hatred was on the rise. Published in 1962, and written at the cusp of the civil rights movement, the travelogue explores the American terrain and maps the consciousness of the American populace, as Steinbeck, returns from Europe in the 1960s to re-familiarize himself with America only to discover, as he writes in a letter to his editor Pat Covici that America was plagued by, “a sickness a kind of wasting disease. There were wishes but no wants…Through time, the nation has become a discontented land” (Steinbeck 1962, 27). Fleshing out the dark underbelly of systemic inequality, and the monstrosity it gave birth to in the form of hedonistic capitalism, requires us to tap into the socio-cultural context that supplies to the maintenance of the income disparity, the erection of systemic barriers, the gradual erosion of the biblical morality and the death of spirituality.

It is within the context of these two works, published nearly two decades apart and at the cusp of two major socio-economic shifts in American history (i.e., the great depression and the civil rights movement) that this paper seeks to look into the works’ points of convergences, the deepening chasm of racism, the exploitation of migrant laborers, and the broader lack of worker and racial solidarity that allows the dominant class/race to erect, bolster and replenish the exploitative structures.

1. DISPOSSESSION AND DEHUMANIZATION

Image by IMDB

The basic foundations of The Grapes of Wrath were laid on a series of articles written by Steinbeck in 1936, published collectively under the title, The Harvest Gypsies. The articles talk about the havoc wreaked by the severe dust storms, that disrupted the ecology and the lifeblood of the American Midwest and the Southern planes rendering them barren and infertile. Steinbeck travelled extensively through these regions and with a journalistic compassion, complied the experiences, the predicament, and the plight of the “dispossessed,” who were uprooted, and forced to migrate, to the cotton farms of California, where the scale of their ill-treatment was only augmented by the gluttonous land owners, farm operators, banks, financial institutions, and the police. The story of the Joad family, which the novel on its most fundamental level traces is replete with instances of never-ending misery and is symbolic of the life of an average “tenant,” in the American Midwest during the Depression era. “The migrants flowed into California, two hundred fifty thousand, and three hundred thousand. Behind them, new tractors were going on the land and the tenants were being forced off” (Steinbeck 1939, 281). As the stampede of the tractors continues, quashing not just the houses, but the dreams of the “dispossessed” and the “homeless,” we learn something about the sinister nature of the unrelenting march of capitalism. In its undying desire to squeeze profit out of material things, it commodifies everything and splinters anything that can thwart its progress. It’s an insatiable entity that devours everything, exploits labourers, and aggravates systemic inequalities.

Steinbeck through his rich use of language and contrivance of vivid imageries creates pictures that display the duality of life, of the haves and the have-nots, of the rich and the poor, of the dispossessed and the owners. In one of the most harrowing and gut-wrenching instances in the novel Steinbeck writes: “The fields were full, and starving men moved on the road. The granaries were full and the children of the poor grew up rachitic…” (Steinbeck 1939, 329). It’s fairly obvious that there is enough for everyone. The children of the poor do not need to grow up rachitic, the poor need not starve. But they have been forced into this kind of impoverished existence, by the state’s negligence and the corporations’ contribution to their destitution.

Another instance where we can see the dehumanization through capitalism in all its shameless splendour is when Steinbeck writes “And the coroners must fill in the certificates-died of malnutrition-because food must rot, must be forced to rot” (Steinbeck 1939, 329). The migrants are not even allowed to fish for potatoes in the rivers. Their lives are only fractionally better off than the “screaming pigs” being butchered in the ditches. It is around this time, suffused with the putrefying smell of the rancid oozing oranges that “in the eyes of the hungry,” the grapes of wrath begin to shape. Symbolically it shows the overbrimming anger that has sown itself deep into the hearts of the migrant population who have borne the brunt of the dehumanization, and destitution, witnessed gruesome death along the road, and are sapped with ceaseless instability.

On his travels with his French poodle Charlie, in the 1960s, he says that “he witnessed very little real poverty,” and that the grinding poverty of the thirties had all but disappeared. But, in the final leg of his journey across Texas and Alabama, he found that a new and nauseating notion had begun to capture the imagination of the States. Anti-black and antisemitic sentiments were on the rise and the notion of humanity and human co-existence were getting suppressed under the weight of brazen racism. In an incident reported in the newspaper about “a couple of tiny Negro children in a New Orleans school,” who were being jeered at by a group of “appalling white women,” Steinbeck writes, “behind these dark mites were the law’s majesty and the law’s power to enforce…while against them were three hundred years of fear and anger and terror of change in a changing world” (Steinbeck 1962, 182). Steinbeck wanted to see these women for himself and went to the school in a taxi. On his way to the school, he stuck up a conversation with the Taxi driver, who to his absolute horror said, “that it was the New York Jews who were causing all this trouble,” and that “the goddamn New York Jews come and stir the niggers up” (Steinbeck 1962, 186). The driver does not stop there and even goes on to suggest lynching as a preventive measure against the spread of the ideas of what I presume to be the ideas stemming from the Civil Rights Movement.

It was incomprehensible for Steinbeck to understand where this racism came from, and the journey itself was in a lot of ways enlightening, in that it forced him to confront the noxious reality and the very real and pervasive existence of racism. He understood that the peace of the 1950s was built on a “mistaken premise” of fixed notions of class and racial boundaries.

2. MARXISM AND WORKER SOLIDARITY

Image by IMDB

“Them goddamn Okies got no sense and no feeling. They ain’t human. A human being won’t live like they do” (Steinbeck 1939, 268). The Joad family’s humanity is snatched away from them, and the service station boy clad in white goes on to say that “no human being could stand being so dirty and miserable.” It highlights the bourgeois tendency to look at the class divide as something that’s the natural outcome of a society built on the principles of equality. The poor remain poor because of their incapacity to rise through the socio-economic ladder and not because of the pitfalls that have been carefully gleaned over the generations to ensure that systemic inequalities remain intact. “The Grapes of Wrath assumes the form of a fictitious description of reality (fictional verisimilitude), in that Steinback like Marx was a keen observer of contemporary society, and when Tom Joad asks “why it is that some people live in squalid poverty, deplorable conditions, and on the verge of starvation while others live in wealth comfort, luxury, and even ostentation,” he is echoing the Marxist notion of unequal distribution of wealth. (Beck and Erikson 56).

Marxism sees dehumanization and alienation as an inevitable outcome of capitalism. It puts forth a theory called the principle of labor exploitation which posits that workers are said to be economically exploited when the “unequal exchange of labor for goods happens. The exchange is unequal when the amount of labor embodied in the goods which the worker can purchase with his income…is less than the amount of labor he expended to earn that income” (Wolff 106). The Californian land-owning class employed a tactic of over-hiring laborers to reduce their cost of production. The workers had no choice but to comply, because as Floyd says, “he’ll pay fifteen cents an hour. An’ you poor bastard’ll have to take it’ cause you’ll be hungry (Steinbeck 1939, 309). Uprootedness can shake the very foundation of one’s identity and once starvation and poverty get thrown into the mix, respectability, humaneness, and individuality get torn to pieces and a growing sense of incapacitation begins to dawn. We find this evolving sense of incapacitation, and even passive acceptance of their inevitable doom, slowly taking hold of the migrant population as they try to navigate the unfamiliar environment, the hostile populace, and the feudal structure of the plantations in California.

Another Marxist theory called the theory of economic determinism divides the population into two halves, the bourgeois, and the proletariat. The proletariats operate in what is called the “base” or at the sub-structural level, which deals with the material means of production. The bourgeois form the superstructure, operate within the cultural world of ideas, and wield absolute power in terms of sowing seeds of discourses and making policies for the entire structure. This gives birth to a class of population that is ideologically emaciated and cannot think beyond their immediate needs and requirements, like satiating hunger. But there are always divergent elements even within this structure, members from the base who rise to challenge the nature of the ideas, being disseminated from the superstructure. Jim Casey, the preacher, for instance, is disillusioned with the notion of God and shifts to, an ideological ground that promotes collective action and solidarity among labourers(socialism). He “talks back,” and that’s crime enough in a system that penalizes dissent, and is built on the premise of silencing the “vulnerable.” Steinbeck calls the migrant population “gypsies by force of circumstance,” whose misery was brewed in the cauldron of capitalism and who are commodified to serve the interest of the bourgeoisie. The death of Casey, the preacher, triggers a fundamental shift in perspective of Tom Joad, who experiences, an epiphanic moment of realization and understands that he must shed his egocentric individualism and embrace the ideas of labour solidarity and social justice. This realization is brought about through experiencing the firsthand misery, of the unsanitary labour camps or shanty towns and the subhuman overcrowded living conditions the migrant workers had to deal with along Route 66. It’s not the nature of the work that’s dehumanizing, but the absolute humiliation at the hands of the authority, that the workers had to experience along their westward journey, which steadily gnawed at their humanity and tore away small chunks of flesh, rendering them hollow, and hurling them into a bottomless pit of insignificance.

3. THE PILGRIM’S MARCH AND STRUCTURAL PARALLELS

Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother/ from Wikipedia

There are a lot of structural similarities that inform the two texts as well. Both texts start on a note of promise, a burgeoning possibility of a better future, with lyrical descriptions of natural landscapes that often rise to the level of poetry. But they end on a note of disillusionment, barely disguising their irritation on “a world of horrific inequities and corruption” that is “grappling with enduring economic and spiritual horrors of the Promised Land” (Napier 55).

The hollowness that plagued the Depression era cast its grimy shadow on the late ’30s, and it was around this time, that James Truslow Adams’ pronouncements regarding the American Dream begin to falter. The westward expansion in American history is notorious for its promises of a better future. The concept of manifest destiny which emerged in the 19th CE reinforced this notion, as if taming the wild, untethered terrain was a pilgrimage, a divinely ordained sacred duty of the white settlers. Also, a journey that brings about a spiritual metamorphosis has always been one of the major thematic concerns for American writers.

The journey which both Tom Joad and John Steinbeck embark on is quite similar, in that they had both been away from home for a long time and had grown estranged from what had been happening in the socio-cultural realm of their homeland. They had both been in exile, Steinbeck in Europe, and Tom Joad in jail. But they are back, and they are on the road.

But instead of a spiritual awakening, they are forced to confront the deplorable human condition, racism, and regionalism that had rooted themselves deep into the hearts and minds of the American populace, hatred borne out of inequality, a constant state of uprootedness, hunger “in the wretched bellies of the children,” and “the naked face of racism and prejudice.” The pilgrims’ march then becomes a journey of disillusionment. Of coming to terms with the actuality and the horror of the class and race divide that lies beneath the veneer of equality. Their journeys are different but converge at the point of their common archaeological exploration of compassion at the sight of human misery. The “Rocinante” (Steinbeck’s pickup truck), and “the box car” then become, symbolically and literally the vehicle for the emergence of this realization.

Steinbeck adds another layer to this process of disillusionment by employing what Tamara Rombold calls “biblical inversion.” So, disillusionment works on two levels, physical perceptive disillusionment, and textual disillusionment. She writes that Steinbeck has inverted, “mythos by eliminating God. He has taken away the miracles and the eschatological elements and has placed all the responsibility and action in the hands of men and women of his own day” (Rombold 163-164). He rejects the utopic notion of a better world and instead takes a realistic, and pragmatic stance. Tom Joad for instance realizes that, when “they’re all workin’ together, not one fella for another fella, but one fella kind of harnessed to the whole shebang- that’s right, that’s holy” (Steinbeck 1939, 136). That’s exactly the not waiting for God kind of philosophy that Steinbeck promotes, and through Tom’s transformation, he also explores the transcendentalist concept of ‘Oversoul.’ Emerson in his essay titled ‘The Over-soul’ first explored this concept, where he writes, “We live in succession, in division, in parts…Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence, the eternal beauty…the eternal One” (See Emerson’s essay 1841). Tom echoes a similar sentiment in his realization that they’re all part of one soul in their abject poverty, and their subjection to humiliation. He calls upon the “Okies” to learn “that all migrants belong to one great family whose claims and importance transcend those of the individual private families” (Berry 19).

Eric Carlson, in his paper about Steinbeck, writes, that his writing includes “an experiential discovery of the processes by which the “physiological man” becomes the “whole man”” (Carlson 175). Tom Joad becomes a whole man when he realizes his position within the broader ambit of humanity. Rose of Sharon, in the closing passage of the novel “which chronicles the misery and death produced by the torrential rain,” in a redeeming act of humanity feeds the starving, moribund man her breast milk. She exemplifies the virtues of resilience and sacrifice and shows life’s “ability to survive and trump over death against forbidding odds” (Berry 19). This transformation from physiological to whole happens in the travelogue (‘60s) as well, but the transformation is rather bitter, in that there is no redeeming act of compassion. There was no space for Martin Luther King Jr., teachings (which Steinbeck endorsed) of “passive but unrelenting resistance” because the youth thought it be “too slow” and something that “will take too long.” The antisemitism of Nazi Germany had seeped into America. And there was hatred, and rueful uncertainty in a world wrestling with inequality, racism, and discontent with the pace at which change was transpiring. His works remain largely relevant and are remarkably prophetic in that America and the world at large, are still grappling with the problems raised in its pages.

. . .

Works Cited:

- Carlson, Eric W. "Symbolism in the Grapes of Wrath." College English 19.4 (1958): 172-175. Digital File. July 2023. <https://www.jstor.org>.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "The Over-Soul." Essays: First Series, Edited by Ed. James Munroe, and Company, 1841, pp. 23-54.

- Erickson, William J. Beck, and Edward. "The Emergence of Class Consciousness in "Germinal" and "The Grapes of Wrath"." The Comparatist 12 (1988): 44-57. Digital File. 30 July 2023. <https://www.jstor.org>.

- Napier, Elizabeth. ""The Grapes of Wrath:" Steinbeck's "Pilgrim's Progress"." The Steinbeck Review 7.1 (2010): 50-56. Digital File. 30 July 2023. <https://www.jstor.org>.

- Rombold, Tamara. "Biblical Inversion in "The Grapes of Wrath"." College Literature 14.2 (1987): 146-166. Digital File. 31 July 2023. <https://www.jstor.org>.

- Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath. Ed. Pat Covici. 75th Year Edition. Penguin Books, 1939. Digital File. July 2023.

- —. Travels With Charley: In Search of America. Ed. Pat Covici. 50th Anniversary Edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1962. Digital File. July 2023.

- Wolff, Jonathan. "Marx and Exploitation." The Journal of Ethics 3.2 (1999): 105-120. Digital File. 1 August 2023. <https://www.jstor.org>.