Witch-hunt is a violent malpractice that is associated with identifying, branding, and executing women as witches. It is an exclusionary practice that focuses on keeping women at the margins of society and as a means of the patriarchal exercise of domination. “Witch-hunting is a three-stage process viz. accusation, declaration, and persecution” (Yadav 170).

The belief in evil magic and witchcraft is common to all societies across the world. It was prevalent in colonial America as well. The Salem witch trial is a famous example of this form of practice in the west. The west without exception has been a part of this barbaric tradition but the scale, frequency, and longevity it has found in India, are surprising and appalling at the same time.

The practice of witch-hunts has existed within the Adivasi population for a long time. It has rooted itself into the collective conscience of the multiple Adivasi tribes over generations. Adivasis, who are the indigenous people of India, is often seen as a marginalized and vulnerable group in society, and they are particularly susceptible to witch hunts due to their cultural beliefs and practices. Although there are some signs of the barbaric practice waning out and dwindling, we still find a few instances of ritualistic sacrifices like this every year.

The rural areas of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh have been the breeding ground for this form of ritualistic sacrificial practice for centuries. Adivasi women are the most vulnerable to witch hunts. They are often accused of practicing black magic or causing harm to others through supernatural means. Once accused, they are subjected to violence, torture, and even death. These women are often ostracized from their communities and denied access to basic services like healthcare, education, and employment.

A closer look into the documented history of this practice in India points to the hunts being carried out during the colonial era as well. It was used by the Adivasis of Singhbhum and Santhal Parganas as a means of resistance “combining both (the obvious) gender but also anti-colonial tension” (Sinha 1672). We’ll also try to understand the gratuitous and unprovoked nature of the violence being cast on women and the kind of role patriarchy plays in promoting and advancing this discriminatory practice.

PATRIARCHY AND UNPROVOKED VIOLENCE

Witch-hunting is a form of gratuitous violence. “For an act to be truly gratuitous, it has to be quite independent of social causality. Because of this independence, the author of mystical versions of gratuitous violence is relatively invisible, motivated principally by the desire for violence itself” (Skaria 111). This unwarranted or unprovoked nature of the violence without any social causality, and with social consensus is what makes this notion and the act itself extremely malevolent.

Gratuitous violence can be understood in opposition to reciprocal violence. Reciprocal violence is seen as an act where the performer of the violence sees themselves as reacting in opposition to violence or potentially violent act. Gratuitous violence frequently tries to mask itself as reciprocal violence. It becomes very evident when we talk about the history of witchcraft and witch trials, which are aimed solely at rendering the execution of witches as violence that is reciprocal and hence justified.

In his book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, Carl Sagan mentions the theologian Méric Casaubon who argued that witches must exist because everyone believes in them. And to substantiate his argument, the theologian says that anything that a vast majority of people believe in must be true. This vox populi and largely patriarchal strain of argument only serve to legitimize mob justice. In the absence of reason in society, justice becomes a twisted and alien concept in which the irrationality of a witch-hunt is accorded precedence over logic, morals, and the spirit of the law.

Patriarchy also forms a significant factor in promoting, fostering, and granting community sanctions for this kind of abhorrent and vindictive violence. “Since every woman was potentially a ‘dakan’ and no man was, the idea of gratuitous violence was evidently isomorphous with that of femininity” (Skaria 131). The most common victims of witchcraft accusations are old, widowed, Dalit, poor, or physically handicapped women. One thing that is quite evident from this list of accused is that they suffer more layers of marginalization than upper-caste Hindu women, women with a husband, or a young woman would. It’s because of the absence of a high caste status, youth, or a husband to shield the women, that the woman becomes vulnerable to being branded a witch. This points to the deeply Brahminical and Patriarchal structure of Indian society.

The Adivasi societies of the western and eastern parts of India have kept this cultural malpractice alive in the name of tradition. The belief has managed to survive the Colonizer’s attempt to eradicate it and is still alive and active among the Adivasis of these regions. We’ll try and trace the contour of this faith’s conservative, patriarchal, violent, and unscientific origins to the colonial era.

WITCH HUNT PRACTICED BY THE ADIVASIS IN THE WESTERN PART OF INDIA

The belief in witchcraft and how it should be dealt with vacillates across time, culture, and geographical areas. The stark differences become evident when we look at the Adivasis of the western part of India who held a very diverse and ambivalent position on the nature and practice of witchcraft. In contrast to women from the plains, Adivasi women from the Aravalli (Bhil) held significant positions in society, yet the flip side of the coin depicts a grim reality.

“Although Adivasi women were relatively powerful in comparison with other women, they were still marginal and subordinate in Adivasi society” (Skaria 131).

This points to the largely patriarchal organization of society within the Bhil community, where, while the women did enjoy equality to a certain degree, they were only fractionally better off than the women from the plains.

The depiction of women as ‘dakans’ in the Adivasi societies of western India was both an acknowledgment of their power and a reflection on the fundamental immorality of that power.

By depicting ‘dakans’ as practitioners of reciprocal violence, the Adivasis of Mewar and the Dangs were in some ways normalizing and according to a (very) partial legitimacy to the exercise of power by particular women in specific situations. (Skaria 132)

The specific situation here refers to the magical aggression inflicted by the witch upon an enemy clan for the protection of her tribe.

“Being a dakan also procured some resources. Such a reputation sometimes secured her a free supper of milk and chicken…As even things praised by a witch, do not thrive, presents are made to her to secure her absence from marriage and other festive occasions.” (Skaria 135)

Being a dakan came with its fair share of advantages as well but when we compare the good against the bad it becomes fairly obvious that no woman in this society would want to identify as a witch because the consequences were dire. They would be stoned to death or driven out of the village if the tribe felt like they were causing some kind of harm. So, the responsibility for natural calamities like drought or flood, or even diseases like fever or smallpox would be placed on their shoulders.

The way the witches are identified is also very interesting because they are utterly unscientific and do not display any kind of regularity in terms of the criterion of being a witch and were based on completely arbitrary grounds. “The so-called witches are identified through certain rituals by traditional witch-finders or witch doctors who are variously known as ‘khonses’, ‘sokha’, ‘janguru’, or ‘ojha’…” (Yadav 170). The women suspected of being a witch had to go through a series of trials and tribulations to prove their innocence. The concept of guilty until proven innocent was used against these women. “She could be forced to dip her hand in boiling oil and take out a rupee coin- if she was innocent, then her hand would not be burnt” (Skaria 124). The completely absurd nature of this proposition essentially hints at the fact that the identification system was already engineered to brand them as witches and no woman, or a man for that matter would have passed this test.

The question which arises out of this situation is how did these cultural- malpractices get a community sanction. The simple answer is patriarchy. By keeping women away from the avenues of power. But a deeper exploration of this situation points to a much more subtle system at play. “By depicting women as practitioners of gratuitous violence and by treating them all as potential ‘dakans’, they vehemently criticized the female exercise of power” (Skaria 132-133) and simultaneously injected a spirit of apathy and disgust in the society towards these women. This disgust eventually culminated in anger, resulting in violence inflicted on these women.

WITCH HUNT AMONG THE TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF SINGBHUM AND SANTHAL PARGANAS

If we go back in time to 1856, the year before the incident that has alternately been referred to as the "First War of Independence" or "The Sepoy Mutiny," something exceptionally cruel was taking place among the tribal populations of what is now the state of Jharkhand.

“Belief in ‘dains’/’dans’/ ‘churails(witches) or ’bongas’(spirits) occupied a central place in Adivasi cosmology and moral economy. ““There is no genuine Santal,” wrote Bodding “who does not believe in witches”” (Sinha 1673). There are two very unusual things to note about this cultural belief. First, the notion of witchcraft had been so thoroughly internalized that even people who were accused of being witches or sorcerers gladly accepted the position despite the agony and consequences, refusing to contest the impeachment. The other peculiarity worth noting is that witch-hunting among the Adivasis of the Santhal Pargana during the colonial period, especially in the 1850s was practiced as a form of resistance against the colonial subjugation of their culture. A categorical motive and a conscious contour of defiance were yoked to this violent malpractice.

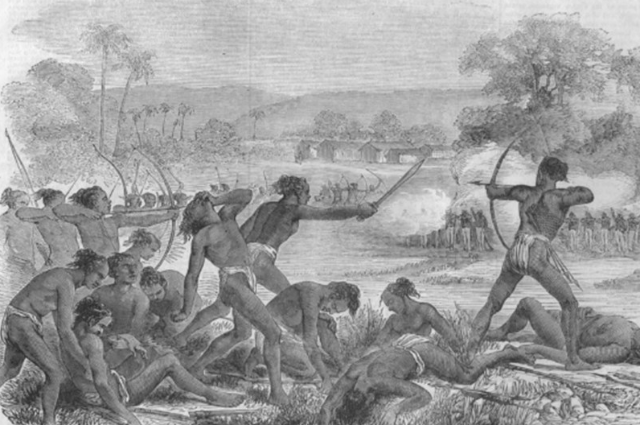

Tracing the contour of this defiance leads us to an interesting juncture in Indian history. Certain historical facts need to be understood before we delve into the exploration of the root cause of this socially sanctioned cleansing. “Wilkinson, the political agent of the Chotanagpur agency in the 1830s banned the practice of ‘sokhaism’. His famous directive (1837) necessitating comprehensive administrative interventions included specific instructions against murders related to witchcraft” (Sinha 1674). This act was seen as an institutionalized suppression of the Adivasi culture and most Adivasis responded to the ban with violence and resistance. The administrative regulation put in place by the British government to curb this violence on women branded as witches was systematically violated during the upsurge of 1856-57. The violence and the resistance played out on two levels. The first was a confrontational and direct form of organized militant action against the colonial forces, and the other was a much more subtle and sinister form of non-confrontational resistance that the Adivasis of the Santhal-Pargana waged against the women of their society.

Witch-hunts represented a form of resistance that did not require direct confrontation with the authority but was also not devoid of any conscious forethought. They represented a form of resistance, “which was seemingly less confrontationist and one with greater community sanction.”

The belief in witchcraft among the Adivasi society was widely accepted and constituted an important section of their worldview. “According to an old Oraon saying the world is as full of disembodied spirits “as a tree is full of leaves”” (Sinha 1673). What the colonial administrators while placing the ban failed to estimate was the extent to which this belief was socially and culturally ingrained. The notion had wedged itself so deep into the native societies’ collective consciousness that it was believed in as a matter of common sense. And the supposed protection of the witches through laws and regulations put in place by the British government was seen as an active incursion on their episteme. Shashank Sinha writes “the belief that witches were flourishing under the benevolent power of the British was increasingly gaining ground.” There was a general feeling among the locals that the ‘dakuns’ had been emboldened by the British sympathy and so ubiquitous was this belief that fissures had already started to appear in the colonial administrative mechanism in the years leading up to 1857.

The civilizing project of the British administrators led them to place these regulatory bans on the practice of witch-hunts and was in some measure responsible for the cruelty that followed. To what extent can we blame the colonizers for this detestable act of violence masquerading as culture is debatable, but what can not be contested is that they failed to understand the finer cultural elements that constituted the cognitive structure of the Adivasi tribes in Chota Nagpur. “To them (Britishers), the very ideas that went to make up the mental framework of the Hos were an anathema” (Choudhury 88). The regulations did not do much to help the women who bore the brunt of this ‘non-confrontational form of violence’. Instead of being suppressed, the practice was pushed underground. The local over-lords continued to promote witch-hunts because they believed they were obligated to preserve their culture and society from evil and malignant forces.

If we are to analyze the statistical evidence of the killings, the data shows a clear spike during the disturbances of 1857-58. The evidence is minimal because most of the cases went unreported. It was because the locals did not perceive these killings as a form of criminal transgression. Rather it was looked at as a form of preventive mechanism.

“The average of the previous five years (before 1857-58) was seven cases in which eighteen persons were implicated” (Sinha 1675). When we compare this to the murders that took place in 1857–1858, which totaled 59 incidents and 218 persons who were accused, we observe the people, “indulging in their superstitious desire of exterminating witchcraft” (Sinha 1675).

It was the momentary withdrawal of authority that permitted them to do so. The execution of women denounced as witches were used for fostering clan brotherhood among the Adivasis. “K Suresh Singh refers to an ‘Ulgulan’ song in which the principal enemies of the tribes-witches, Europeans, and other castes(dikus)- are placed in the same category” (Sinha 1675).

Sinha refers to the practice as a form of extra-political resistance. The problem with this form of extra political resistance was that it targeted a particular section(gender) of society based on minimal evidence and an unscientific methodology of identification. It is essentially an extreme form of the exercise of patriarchy where the incapacity of the men in the community to fight against the colonial armies leads to frustration and that resentment precipitates in violence against the women. A common denominator that informs witch-hunts across time space and geography, races cultures, and traditions seem to be an extremely malevolent exercise of patriarchy that relegates women to the margins of society and intensifies the cruelty in an exploitative social-power structure.

. . .

WORKS CITED:

- Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Random House, 1995. February 2023.

- Sinha, Shashank. "Witch-Hunts, Adivasis and the Uprising in Chotanagpur." Economic and Political Weekly 42 (2007): 1672-1676. February 2023.

- Skaria, Ajay. "Women, Witchcraft and Gratuitous Violence in Colonial Western India." Oxford Journals (1997): 109-141. February 2023.

- <https://www.jstor.org/stable/651128>

- Yadav, Tanvi. "Witch Hunting: A Form of Violence against Dalit Women in India." CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion 1.2 (2020): 169-182. February 2023.

- <https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48643572>.