Photo by Bailey Zindel on Unsplash

Alien species (Synonyms: non-native, non-indigenous, foreign, exotic)

A species, subspecies, or lower taxon introduced outside its normal past or present distribution; includes any part, gametes, seeds, eggs, or propagules of such species that might survive and subsequently reproduce.

Invasive alien species

An alien species whose establishment and spread threaten ecosystems, habitats or species with economic or environmental harm. These are addressed under Article 8(h) of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

ABSTRACT

While the issue of invasive alien species has important biological components, the human proportions deserve much greater attention. First, practically all of our planet’s ecosystems have a strong and increasing anthropogenic component that is being stuffed by the increasing globalization of the economy. Second, people are designing the kinds of ecosystems they find productive or agreeable, incorporating species from all parts of the world. Third, growing travel and trade, coupled with decreasing customs and quarantine controls, mean that people are both intentionally and negligently introducing alien species that may become invasive. And fourth, the issue has important logical dimensions, requiring people to examine fundamental ideas, such as “native” and “natural”. The great increase in the introduction of alien species that people are pinpoint for economic, aesthetic, accidental, or even psychological reasons is leading to more species invading native ecosystems, with adverse results: they become invasive alien species (IAS) that have significant detrimental effects on both ecosystems and economies.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive alien species are species that are introduced into new areas and, once there, are able to adapt, become established, reproduce and spread, cleansing the environment, creating new populations and impacting on biodiversity, health and the economy. These can cause numerous problems, such as acting as predators antithetical the growth of native species, altering adobe causing physical and chemical changes to the soil, competing for food and space; bruising with native species, introducing new parasites and diseases.

A biological breach can also have an impact on human health since several species can transmit disease, cause allergies, and even be poisonous. The brunt on the economy can be significant, leading to a reduction in or even the exodus of fishing, livestock breeding and crop cultivation, and bruise to the tourism industry. Not all introduced category are invasive. Some of them are unable to comply to their new environment or spread freely, as is the case with many farm animals and garden plants, meaning that they are not a hazard to the area. Others acclimatized and spread without damaging the environs, such as potatoes and corn, becoming entrenched species.

Invasive alien species are plants, animals, pathogens and other organisms that are non-native to an ecosystem, and which may cause economic or environmental harm or adversely affect human health. In particular, they impact diversely upon biodiversity, including drop or elimination of native species - through competition, predation, or communication of pathogens - and the interruption of local ecosystems and ecosystem functions. Invasive alien species, introduced and/or spread outside their natural habitats, have concerned native biodiversity in almost every environs type on earth and are one of the greatest threats to biodiversity. Since the 17th century, invasive alien species have contributed to nearly 40% of all animal extinctions for which the cause is known (CBD, 2006).

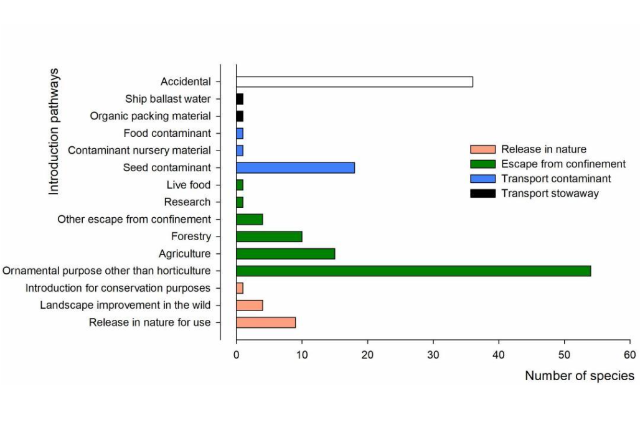

HOW INVASIVE SPECIES ARE INTRODUCED

Exotic species travel around the world in the most abrupt ways, taking root in places that are thousands of kilometers away from their essential habitats. This is sometimes the result of human interference whether intentional or not and sometimes caused by natural phenomena. Below, we look in more detail at some of the causes linked to human activity:

The trade-in wildlife: Trade in exotic plants and animals is the main source. Illegal piracy of wildlife is a crime that turns over between 10 and 20 billion euros a year, according to the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF).

- Tourism: Visiting other countries supply to the spread of foreign species, whether intentionally or otherwise.

- Hunting and fishing for leisure: In the past, these two activities were responsible for the introduction of animals such as the barbary sheep and the catfish across large parts of Europe.

- Transport and international trade: Invasive species often travel restricted in aircraft holds, shipping containers and ships' hulls.

- Abandoned pets: Raccoons, monk parakeets and red-eared slider turtles are examples of exotic pets that have colonised ecosystems after escaping or being discarded.

- Crops and the fur industry: The fashion industry and horticulture have also been arch for mammals such as the American mink in Europe, and for plants such as the raised prickly pear in Africa and Oceania.

FAST FACTS

- Invasive alien species have since the 17th century gratuitous to nearly 40% of all animal extinctions for which the cause is known.

- Annual environmental losses caused by introduced pests in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, India and Brazil have been calculated at over US$ 100 billion.

- Chytridiomycosis caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, pushed populations of amphibian species to decline and even go abolished in western North America, Central America, South America, eastern Australia, and Dominica and Montserrat in the Caribbean. The fungus caused sporadic deaths in some amphibian populations, with 100% mortality in others. 80% of the threatened species in the Fynbos biome of South Africa are endangered due to invasions by alien species.

- Invasive alien species can transform the structure and species composition of ecosystems by dominating the ecosystems and repressing or excluding native species.

- Because invasive species are often one of a whole collection of factors affecting particular sites or ecosystems, it is not always easy to determine the proportion of their impact.

- Major pathways of invasive alien species in aquatic environments are hull fouling and the release of ballast water from ships. Live bait for recreation fishing, escapes and releases from aquaculture or aquariums, are also serious problems.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ALIEN AND ALIEN INVASIVE SPECIES BELOW:

- An alien species is a species introduced outside its normal circulation. According to experts, alien species become ‘invasive’ when they are introduced deliberately or accidentally outside their natural areas, where they out-compete the native species and upset the ecological balance.

- The most common characteristics of invasive species are rapid reproduction and growth, high dispersion ability, ability to survive on various food types, and in a wide range of environmental conditions and the capability to adapt physiologically to new conditions, called phenotypic plasticity.

- The alien invasive species are external to an ecosystem. They may cause economic or environmental harm or even skeptically affect human health.

CAUSES AND IMPACTS OF INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES

Globalization has resulted in greater trade, transport, travel and tourism, all of which can facilitate the introduction and spread of species that are not native to an area. If a new habitat is similar enough to a species’ native habitat, it may endure and reproduce. For a species to become nosy, it must successfully out-compete native organisms for food and habitat, spread through its new environment, increase its population and harm ecosystems in its introduced field.

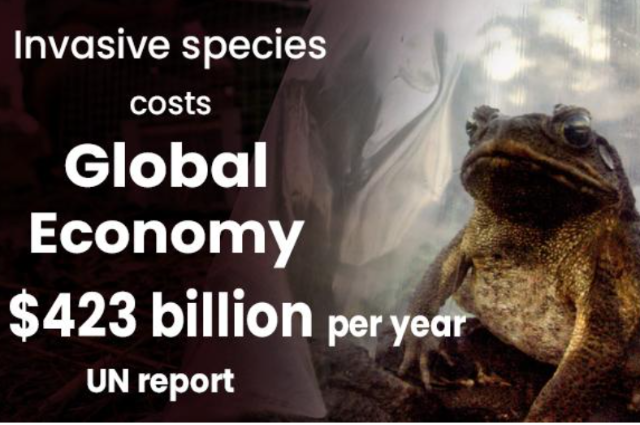

Most countries are grappling with complicated and costly invasive species problems. For example, the annual environmental losses caused by introduced pests in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, India and Brazil have been calculated at over US$ 100 billion (CBD, 2006). Addressing the problem of invasive alien species is urgent because the threat is growing daily, and the economic and environmental impacts are severe.

IAS occur in all economic groups, including animals, plants, fungi and microorganisms, and can affect all types of ecosystems. While a small percentage of organisms carried to new environments become invasive, the negative impacts can be extensive and over time, these additions become consequential. A species introduction is usually factored by human transportation and trade. If a species new habitat is similar enough to its native range, it may endure and reproduce. However, it must first get by at low densities, when it may be difficult to find mates to reproduce. For a species to become invasive, it must successfully out-compete native organisms, spread through its new environment, increase in population density and hazard ecosystems in its introduced range. To summarize, for an alien species to become invasive, it must arrive, survive and bloom.

Common characteristics of IAS include rapid reproduction and growth, high diffusion ability, phenotypic plasticity (ability to adapt physiologically to new conditions), and ability to survive on various food types and in a wide range of environmental conditions. A good predictor of invasiveness is whether a species has successfully or unsuccessfully stormed elsewhere.

Farmers have been fighting apparel since the very beginnings of agriculture, and disease organisms have been a major focus of physicians for well over a hundred years. But the general global problem of invasive alien species has been brought to the world’s attention only recently by ecologists who were anxious that native species and ecosystems were being confused (e.g., Elton, 1958; Drake et al., 1989). Much of the work to date on IAS has focused on their biological and ecological characteristics, the susceptibility of ecosystems to invasions, and the use of various means of control against invasive.

Nonetheless, the problem of IAS is above all a human one, for at least the following reasons:

- People are largely responsible for moving eggs, seeds, spores, vegetative parts, and whole organisms from one place to another, notably through modern global transport and travel;

- While some species are capable of invading well-protected, “perfect” ecosystems, IAS more often seem to invade habitats altered by humans, such as agricultural fields, human settlements, and roadways;

- Many alien species are deliberately introduced for economic reasons (a major human endeavour), implying that those earning economic benefits should also be responsible for economic costs should the alien become invasive.

- The dimensions of the problem of invasive alien species are defined by people, and the response is also designed and implemented by people, with differential impacts on different groups of people.

WHAT'S THE PROBLEM?

Increasing travel, trade, and tourism identical with globalization and expansion of the human population have facilitates intentional and unintentional movement of species beyond natural biogeographical barriers, and many of these alien species have become invasive. Invasive alien species (IAS) are considered to be one of the main direct drivers of biological diversity loss at the global level1, 2. It is clear that IAS can produce considerable environmental and economic damage, and their negative effects are incensed by climate change, pollution, habitat loss and human-induced disturbance. Increasing influence by a few invasive species increases global homogenization of biological diversity, reducing local diversity and uniqueness.

IAS can change the community system and species composition of native ecosystems directly by out-competing endemic species for resources. IAS may also have important indirect effects through changes in nutrient cycling, ecosystem function and eco-friendly relationships between native species. IAS can also cause downward effects with other organisms when one species affects another via transitional species, a shared natural enemy or a shared resource. These chain reactions can be ambitious to identify and predict. Furthermore, combined effects of multiple invasive species can have large and complex impacts in an ecosystem. Invasive species may also alter the evolutionary pathway of native species by competitive exclusion, slot displacement, hybridization predation, and ultimately extinction. IAS themselves may also emerge due to interactions with native species and with their new environment.

IAS can directly affect human health. Infectious diseases are often IAS imported by travellers or factored by exotic species of birds, rodents and insects. IAS also have indirect health effects on humans as a result of the use of pesticides and herbicides, which penetrate water and soil.

WHY DOES IT MATTER?

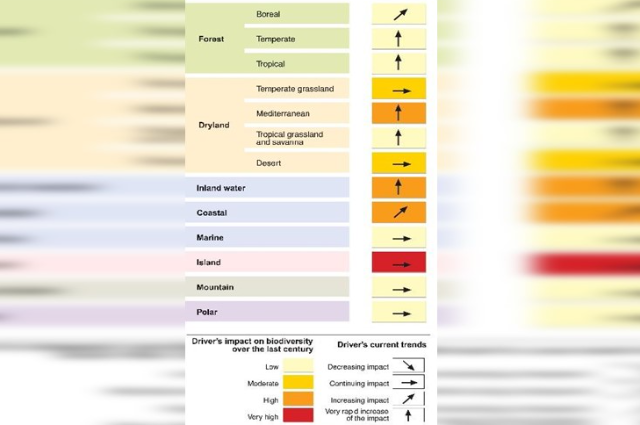

Invasive alien species have invaded and affected native biota in almost every ecosystem type on Earth, and have affected all major taxonomic groups1. In economic terms, the costs of invasive alien species are symbolic. Total annual costs, including losses to crops, pastures and forests, as well as environmental damages and control costs, have been conservatively estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars and possibly more than one trillion2. This does not include valuation of species extinctions, losses in biodiversity, ecosystem services and aesthetics.The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment concluded that the relative impact of invasive alien species on biodiversity has varied across biomes, and that for all biomes, the impact is either steady or increasing as follows:

HOW TO CONTROL AND REDUCE THE IMPACT OF INVASIVE SPECIES

The introduction of these species has a detrimental effect on the environment, but also on food safety, the control of diseases such as malaria and dengue fever, and on the economy. The IPBES valuation that in Southeast Asia alone, invasive species are responsible for the loss of $33.5 billion per year.

This harm could be largely avoided or diminished by applying a diversified strategy that takes into account the following points:

- Legislation to constrain imports of exotic species.

- Prevention through greater diligence of entry points.

- Detection and rapid response to evade species becoming established.

- Destruction of invasive species that have successfully spread.

- Pest control where elimination is not possible.

INVASIVE SPECIES EXAMPLES

There is a long list of insects, animals, and plants that have spread across the world, exposing biodiversity. Some of them are outlined below:

This small mammal affects diverse protected species of amphibians, fish, and mammals such as the European mink, which has been driven to the edge of extinction.

Hottentot fig (Carpobrotus edulis). This plant is originally from Peru, and is often used as decorative plant because of itseye-catching flowers. However, it growth obstruct the development of other species by taking over the ground occupied by the native vegetation.

WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE?

Invasive alien species (IAS) are a global concern that requires international cooperation and actions. Preventing international movement of IAS and swift detection at borders are less costly than control and eradication. Preventing the entry of IAS is carried out through inspections of international shipments, customs checks and proper quarantine regulations. Prevention requires collaboration among governments, economic sectors and non-governmental and international organizations.

HISTORICAL DIMENSIONS

Because of a long geological and evolutionary history, our planet has very distinct species of plants, animals, and micro-organisms on the various continents, and in the various ecosystems. As a broad illustration, Africa has gorillas, Indonesia has orangutans, South America has monkeys but no apes, and Australia has no non-human primates at all. Even within the continents, most species are restrained to particular types of habitats; gorillas live in forests, zebras mostly in grasslands, and addax in deserts. Oceanic islands and other geographically isolated ecosystems often have their own suites of species, many found nowhere else (termed “endemic species”); about 20% of the world’s flora is made up of insular endemics, found on only 3.6% of the land surface area.

Geographical fence have ensured that most species remain within their region, thus resulting in a much greater species abundance across the planet than would have been the case if all land masses were part of a single continent. This historical biogeographical framework provides the basis for acute concepts of native and alien species. It is also important to recognize that biogeography is dynamic, as species expand and obligation their ranges and the contents of ecosystems change as a result of factors such as climate change (Udvardy, 1969).

HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF THE CAUSES OF SPECIES INVASIONS

Global trade has enabled modern societies to benefit from the unprecedented movement and establishment of species around the world. Agriculture, forestry, fisheries, the pet trade, the horticultural industry, and many industrial consumers of raw materials today depend on species that are native to obscure parts of the world. The lives of people everywhere have been greatly enriched by their access to a greater share of the world’s biological diversity, and advancing global trade is providing additional opportunities for further such enhancement. Most people intensely welcome this globalization of trade, and growing incomes in many parts of the world are leading to increased demand for exotic products. North American nursery brief, for example, offer nearly 60,000 plant species and varieties to a global market, often through the Internet (Ewel et al., 1999). A generally anonymous side effect of this globalization is the introduction of alien species, at least some of which may be invasive.

HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF THE CONSEQUENCES OF INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES

IAS have many negative brunt on human economic interests. Weeds reduce crop yields, increase control costs, and decrease water supply by degrading drainage areas and freshwater ecosystems. Tourists unwittingly introduce alien plants into national parks, where they degrade protected ecosystems and drive up management costs. Pests and pathogens of crops, livestock and trees destroy them outright, or reduce yields and increase pest control costs. The discharge of equilibrium water introduces harmful aquatic organisms, including diseases, bacteria and viruses, to both marine and freshwater ecosystems, thereby degrading comically important fisheries and competitive opportunities.

And recently-spread pathogens continue to kill or disable millions of people each year, with profound social and economic significance. While considerable ambiguity remains about the total economic costs of invasions, estimates of the economic costs of particular invasive’s to particular sectors indicate the seriousness of the problem.

Globalization is bringing with it a series of new medical threats, many of which can be considered a sub-set of the IAS problem. Viruses are a particular problem because they are so difficult to conflict; while vaccines for viruses such as smallpox, polio, and yellow fever have proven effective, cures remain elusive and even very substantial investments to find a cure for AIDS have thus far proven only kind of effective. Even worse, the global changes that are affecting many parts of the world are expected to lead to the expansion of the ranges of many viruses that are potentially dangerous to humans. When people invade formerly unoccupied wilderness areas, this brings them into contact with a wider range of viruses and bacteria, while air travel carries them around the globe before the symptoms become apparent. Infectious disease agents often, and maybe typically, are invasive alien species (Delfino and Simmons, 2000). Unfamiliar types of infectious agents, either acquired by humans from tamed or other animals, or imported negligently by travelers, can have devastating impacts on human populations. Pathogens can also undermine local food and livestock production, thereby causing hunger and drought. Examples:The bubonic plague (caused by Pasturella pestis) spread from central Asia through north Africa, Europe, and China using a beetle vector on an invasive species of rat (Rattus rattus) that came originally from India.

The viruses carrying smallpox and measles spread from Europe into the western hemisphere shortly following European colonization. The low resistance of the endemic peoples to these diseases helped bring down the mighty Aztec and Inca empires.

The Irish potato famine in the 1840s was caused by a fungus (Phytophtora infestans) introduced from North America that attacked potatoes, with devastating impacts on the health of local people.

The influenza A virus has its origins in birds but multiplies through domestic pigs which can be infected by multiple strains of avian influenza virus and then act as genetic “mixing vessels” that yield new recombinant-DNA viral strains. These strains can then affect the pig-tending humans, who then infect other humans, especially through rapid air transport.

HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF THE RESPONSE TO IAS

Human societies seem to have a great capacity for contradiction, with quarantine inspections, for example, being the responsibility of the same governments that promote globalization that undermines government capacity to apply effective quarantine measures (Low, this volume). Governments have a responsibility to provide regulations in the public interest, but current economic orthodoxy argues that global trade is fostered through removing regulations that may constrain such trade, such as restrictions that may prevent the introduction of a probably invasive alien species.

These discrepancies help to underline the conflict of interests between global trade and the control of IAS, and the challenges to current management measures and legal frameworks.

CONCLUSIONS

IAS are able to invade new habitats and constantly extend their distribution, thereby representing a threat to native species, human health, or other economic or social interests. One curious human dimension is the fact that a strong consent can be built that many specific invasions are harmful, including killer bees, water hyacinth, kudzu, spruce budworms, various pathogens, and agricultural weeds. The issue of IAS, therefore, can bring together interest groups that might otherwise be in hostility, such as farmers and conservation groups. Bringing in the human dimensions can shift the focus from the IAS itself to the human actions that facilitate its spread or manage its control, and implies that focussing directly on the invasive species is likely to provide only emblematic relief. A more fundamental solution requires addressing the ultimate human causes of the problem, often the economic motivations that drive or enable species introductions.

Humans, with all their diversity of twist, strengths, and weaknesses, are at the heart of the problem of IAS and, paradoxically, also at the heart of the solution. Given the ultimate human motivations of survival, reproduction, and perhaps spiritual fulfillment, and the more immediate economic motivations, people might be encouraged to commit to addressing the problem of IAS by such measures as:

- Helping the public to identify and grasp values that have a direct relationship to basic needs and are environmentally sound, thereby also achieving longer term benefits. This might include promoting the concept of “community”, including native species, as a value that can balance the powerful economic values of global trade.

- Developing conservation practices and ethics that affirm the importance of natural ecosystems, for example by refining distinctions between natural and anthropogenic conditions, innovative ways to use ecosystems without losing biotic diversity, and promote shifts in societal values toward more respect for nature.

- Identifying measures that work within existing value systems, but encourage people to backing conservation measures (for example, through the use of economic incentives and disincentives).

- Ensuring that the costs of controlling IAS are “incarnate”, paid by those who are benefiting from the intentional introduction and those responsible for unintentional introductions.

- Linking the regard about invasive alien species to the drive for development that motivates most people, and virtually all governments, today.

- Including human dimensions in the various obligation, agreements, and guidelines on IAS, such as those developed under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

- When introducing new species, use risk assessment procedures that take into account future changes in usage and demonstrate that – to the best of current knowledge – adverse impacts will be limited.

RESEARCH PRIORITIES FOR HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF IAS INCLUDE:

- Identifying opposing interests regarding benefits and risks of introductions, substantiating evaluations of those benefits and risks, and determining the likely distribution of benefits and risks among sectors of society (Ewel et al., 1999).

- Identifying elemental causes for human choice in relation to IAS, including identifying how human beliefs about specific invasive species influence their actions to promote or limit the spread of that species.

- Ascertaining what is known scientifically about the pervasive human affinity for other species. Is “biophilia” an instinctive behaviour? Is it a conditioned response? Does it lead to more alien species being imported? Can the human behaviour that stems from this attraction to other species be modified and redirected? If so, how?

- Evaluating potentially useful domestic organisms rather than non-indigenous ones, thereby reducing incentives for introductions.

- Illuminate the interactions between the media, the public, and scientists/ conservationists.

- Identifying the views of homegrown peoples and other interest groups about invasive alien species.

- Carrying out a predictive modelling exercise to project what might be the issue if we are unable to slow or stop the spread of IAS.

The global economy, with increased transport of goods and travels, has simplify the movement of live species over long distances and beyond natural boundaries. While only a small percentage of transported organisms become invasive, they have an astounding impact on the health of plants, animals and even humans—threatening lives and affecting food security and ecosystem health. Their negative impact on the economy costs countries billions of dollars in losses to agricultural production and some trillion dollars of environmental cost worldwide every year. Once established, eradication is the most enticing solution, but it can be very expensive to do. Prevention is still the best answer. The negative effects of invasive alien species on biodiversity can be extended by climate change, habitat destruction and pollution. Isolated ecosystems such as islands are particularly affected. Loss of biodiversity will have major consequences on human well-being. This includes the decline of food diversity, leading to malnutrition, drought and disease, especially in developing countries. It will also have an important impact on our economy and culture.

The issue of invasive alien species is caused by human activities identical with international movement, but measures have to be taken at national and local levels. International cooperation can aid it. Prevention is the first step, but where the damage has been done, it can still be reversed if we all work together.