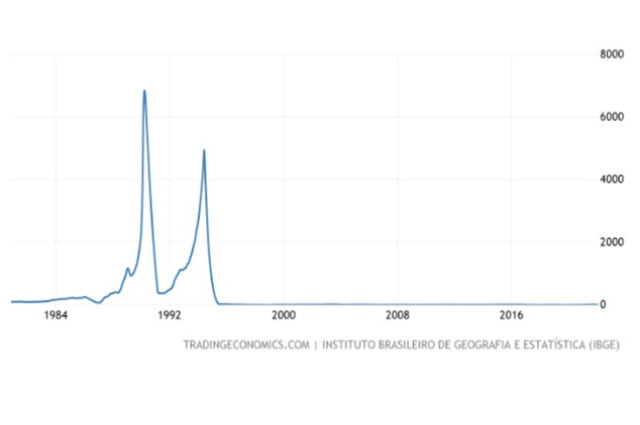

Brazil has been the world's largest producer of coffee for the last 150 years. Being the largest national economy in Latin America, the world’s ninth-largest economy, and the eighth largest in purchasing power parity (PPP), it is hard to believe that less than three decades ago the country was battling crippling inflation. The transition was not smooth. The Brazilian economy has always been a series of economic roller coasters. After a decade of failed attempts at stabilizing the economy, some of which aggravated the problem, in 1992, Brazil managed to formulate a successful strategy which reduced from 303% YoY in the early eighties to a single digit in 1998.

CAUSES

1. MILITARY DICTATORSHIP:

Brazil had always been under military rule. In fact, the country had seen two dictatorship periods: During Vargas Era (1937-1945) and during the military rule (1964-1985) under the Brazilian military government. Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira, 21st president of Brazil during the dictatorship era, undertook large-scale projects under Target Plan(1956) and National Development Plan (1972), which focused on improving the country’s infrastructure. Some of these large public projects included the construction of The Itaipu Dam, Trans-Amazonian Highway, and Rio-Niteroi Bridge.

The government believed that investing in such projects could spur private and foreign investment which would, in turn, result in the growth of the country’s economy. Besides relying on government funds, the plan additionally relied on large foreign investments. These initiatives resulted in massive growth in the economy of the country but not without a price.: the cost of living increased with the rising exchange rate, while Brazil’s enormous foreign debt increased. That process also led to a surge in the number of public banks, to finance their fiscal deficits, and to the creation of some of the largest Brazilian SOEs.

2. OIL CRISIS:

Brazil relied heavily on oil imports during the 1970s. As the oil prices quadrupled during the first oil crisis (1973), the country found itself in a pickle. Although it presented challenges to the continuation of committed high-end infrastructural projects, the Brazilian government decided to carry forward even if it meant borrowing from abroad lenders and increasing external debt.

During the oil crisis, one of the main goals of the country was to reduce dependence on oil imports by focusing on country-owned oil projects. To wean the nation away, the government spent a considerable amount on research and development of alternative energy sources.

Ethanol produced from sugar cane has played a key role in Brazil's effort to find a substitute for oil. National oil production has been increasing by 20 percent a year, and in 1982 oil imports accounted for 68 percent of the country's consumption, down from 85 percent in 1974.

The country also imposed limitations on the use of petroleum. Brazil has had a long period of high inflation. It peaked at around 100 percent per year in 1964, decreased until the first oil shock (1973), but accelerated again afterward, reaching levels above 100 percent on average between 1980 and 1994.

3. POLITICAL INSTABILITY:

The 21 years of dictatorship finally came to an end in 1985, when the first democratic elections were held. While the military regime played a significant role in industrial development, they could not curb the uncontrollable high inflation and repeated external crisis. But, the advent of democracy did not bring prosperity either. After the establishment of democracy, President Jose Sarney launched multiple stabilization policies which, more or less, proved to be unsuccessful.

GOVERNMENT MEASURES

- Crusado Plan (1986) - The basic objective of the plan was to halt the acceleration of inflation by stopping the fall of wages. It was based on the theory of inertial inflation. Wages were frozen for a year yet, the result was an increase in inflation to a new level of 600%.

- Bresser Plan (1987) - aimed to improve the healthy functioning of the economy by reducing inflation to a manageable level rather than eliminating inflation. The plan began to collapse in the latter quarter of 1987 and was predominantly due to the significant raises government staff were given.

- Summer Plan (1989) – Along with the price freeze, the government privatized SOES and laid-off civil servants. The aim was a limitation of inflation rather than eradication.

- Collor Plan (1990) – named after President Fernando Collor, the aim was to eradicate inflation in one go. The inflation had reached the heights of 5000%. The plan involved a reduction in the stock of money through freezing bank accounts and restricting financial markets. This plan succeeded in managing the hyperinflation by reducing monthly inflation from 81.3% in March 1990 to 11.3% in April 1990 (Pereira & Nakano, 1991, p. 44). In July 1990 when price controls were lifted, Brazil saw the re-emergence of high inflation.[47]

THE REAL PLAN

In the midst of mounting inflation and a series of failed stabilized plans, The real plan appeared like a knight in shining armor. The plan aimed to "The establishment of balance in the government's accounts to eliminate the main cause of Brazilian inflation.” Initiated by Fernando Henrique Cardoso in 1994, first as Minister of Finance and later as President of Brazil, the plan sought to transform the Brazilian economy by privatization, financial sector reforms, attracting foreign investment, and opening the country’s economy to the world.

In June 1994, one month before the introduction of the real as legal tender, the annual inflation rate was around 5,150.00%, whereas by December 2001, the annual inflation rate had fallen dramatically to approximately 10.0%

The inflation at the time was increasing so rapidly that the prices had to be changed twice or thrice a day. This led civilians to expect darker times. The currency had lost its meaning. To tackle this problem, the government introduced a new fictitious unit of account, called URV (Unidade Real de Valor). Its initial value in Cruzeiros Reais was approximately equal to one dollar, at the market rate of February 28, 1994, ie Cr$ 647,50 647,50 in URVs. Fictitious in the sense that it existed only in name.

All the transactions were done in Brazilian currency Cruzeiros. All the goods were marketed in both URV and Cruzeiros but on the one hand, where Cruzeiros increased by hours, URV remained stable. The civilians didn’t really grasp the concept and objective of the virtual currency but over time unchanging URV gave them a sense of stability.

In the coming weeks, they sponsored dissemination of URV government denominations in order to replace all existing indexation devices including implicit discounts and premiums in the pricing of deferred obligations

One of the major problems associated with URV adoption process was the existence of two competing means of payment. The widespread use of the URV, in itself, was nothing more than a perfecting of the process of indexation with a considerably increased level of uniformity in the indexation process.

The law established URVs, to be issued as a "full" currency provided that, at this moment its name be changed to "Real". Soon after, the new currency “Real” was legalized and the old currency “Cruzeiros Reais” was demonetized.

Along with the introduction of a new currency, one of the major decisions government took was to cut back government spending, tightened tax collection, and collected on debts state governments owed to the federal government. It also opened the economy to the world. Brazil had always been a closed economy with its main focus on an inward-oriented growth model. Loans are once again flowing to Brazil, partly because the International Monetary Fund has stepped in with $2.5 billion to tide the nation over.

CONCLUSION

Over the years, Brazil's resilient economy has pulled through obstacles thrown at it. The stabilization program redefined the country’s trade orientation. Even though they failed to fulfil their main objective, several initiatives taken by the government to subdue inflation, they did manage to take several steps in the right direction. Building infrastructure and reducing the use of oil had benefited the economy in numerous ways. From the establishment of a new currency to be the largest exporter of coffee, Brazil has come a long way. Even after being faced with such an adverse situation, it has managed to come out almost unscathed. Brazil is far from a prosperous economy and it has a long way to go.