INTRODUCTION

All educational levels continue to emphasize the importance of student motivation. Education circles have articulated a variety of student motivation strategies, but educators are still figuring out the best models to motivate students in the classroom. Praise is one especially often used method of student motivation that has come under fire and examination in the modern classroom. Praise has the potential to be an effective motivator for students, but only when used appropriately and with the right goals in mind. In order to motivate students, this article reviews research on how teachers should be using praise in the classroom. It focuses on how praise-notes can be used to effectively motivate students' performance and engagement. Through practical recommendations for classroom use, the benefits of praising notes as a motivational tool are addressed and illustrated. Also the results provide in-depth examples of how the productive traits appear in actual classroom practice. The findings advance our knowledge of which particular types of teacher-student discussion benefit learning and how teachers might actively promote certain types of dialogue.

1. PRAISE NOTES IMPULSE THE STUDENT’S PRODUCTIVITY:

At all levels of education, student motivation has long been a crucial subject, particularly as student populations become more and more diverse. The different aspects that affect student motivation have long piqued the interest of educators and society at large. At the moment, motivation can be seen as a complicated, context-sensitive, dynamic, and variable construct. Discussions about student praising have been more prevalent and diverse in regard to student motivation. According to Carol S. Dweck, praise can be an effective tool for encouraging students to take on intellectual challenges, appreciate the value of effort, and deal with setbacks. However, when used incorrectly, praise can have a negative effect on students by making them passive and reliant on other people's opinions. It's obvious that a lot depends on how praise is used in the classroom. Teachers risk unwittingly disadvantaging or injuring their children if they lack a fundamental understanding of how praise can be utilized appropriately.

It is crucial for teachers to comprehend the potential benefits of motivational techniques at all educational levels.

The level of student participation continues to be a major problem for educators. It is normal for teachers to commend students for their efforts to contribute positively to a productive classroom environment and for their successful performance.

Although attempts at praise are frequently made out of a sincere desire to support and uplift students, few teachers are likely to have looked into the complicated nature of praise as it relates to student motivation or taken into account the ways praise can perhaps harm kids.

Research on Praise as Motivational Classroom Tool:

The use of praise in educational settings appears to be supported by research, but only when employed in specific circumstances. According to Dweck, when we just acknowledge a student's brilliance, failure becomes more intimate and, thus, more embarrassing. As a result, students are less equipped to handle their failures. According to Dweck, these unfavorable effects of praising intelligence are real and equally potent for both high and low achievers. When seeking to use praise, instructors must constantly keep in mind that pupils can be sensitive to comments made regarding their individual features. Dweck goes on to say that professors should congratulate students, but do so in a way that is excited about the tactics they use, rather than how their success exposes a quality they may perceive as fixed and beyond their control. Dweck is differentiating between praise for people and praise for processes by emphasizing the latter over the former. While process praise emphasizes the work, efforts, and procedures necessary to complete a task, person praise concentrates more on the qualities associated with a particular person.

Haimovitz and Henderlong-Corpus examined the effects of person praise and process praise on the motivation of 111 students and discovered that process praise increases intrinsic motivation and perceived competence more than person praise, while person praise lowers motivation for students when process praise is used. According to Conroy, Sutherland, Snyder, Al-Hendawi, and Vo, process praise is preferable to person praise for boosting student performance (e.g., increasing students' accurate answers and the amount of work they finish) and improving the classroom environment. Beyond this agreement, Conroy et all’s research highlights the significance of taking individual and cultural differences in students into account when utilizing praise.

For instance, praise may be received differently by students with varied socioeconomic origins and skill levels, thus these variations must constantly be taken into account. Effective praise, according to the authors, should be teacher-led, include specific statements about the appropriate behavior student’s exhibit, come right after a desired behavior, take into account where a student is in the process of mastering a particular skill, be sincere, and refrain from comparisons between students.

Haydon and Musti-Rao found that behavior-specific praise, which rewards a particular academic or social behavior with a verbal comment, had a favorable impact on student participation, classroom atmosphere (specifically, a significant reduction in disruptive classroom behavior), and teacher-student interactions, especially when used right after a desired behavior. The authors also came to the conclusion that teachers could benefit from honing their praise-giving skills and that this is an underutilized teaching tactic. The study by Partin, Robertson, Maggin, Oliver, and Wehby demonstrates that teacher praise as positive reinforcement for students' appropriate behavior, as well as the provision of high rates of opportunities for students to respond (OTR) correctly to academic questions, tasks, or demands, decrease inappropriate student behaviors and increase appropriate behaviors. Increased OTR and consistent, appropriate use of teacher praise may also be a crucial first step in creating predictable and encouraging classroom environments.

Despite the fact that process praise is often supported by research, there has been recent literature that compares the effectiveness of process praise to that of person praise and no praise at all. According to a research by Skipper and Douglas, participants in the process condition did not significantly vary from participants in the control group (no praise). This research raises the possibility that process praise may not always be beneficial. Students respond to person, process, and no praise in similarly good ways when they are succeeding, but it was found that person praise was particularly harmful, which is consistent with other research findings.

Some educators such as Alfie Kohn believe that praise can have particularly detrimental outcomes for children. Kohn argues that praising a child can be seen as a manipulative act that could create praise junkies, decrease student interest in activities, steal pleasure, and reduce student achievement. For example, if a child is told he or she has done a good job on a particular task, he or she may be subsequently less motivated to continue working hard on that task. Despite pointing out the dangers of praising children, Kohn acknowledges that all of expressions of delight are not harmful, instead, we need to consider our motives for what we say and the actual effects of doing so.

Despite Kohn’s opposition to praise in the classroom, the key consensus information from the described research above points to the beneficial use of praise in relation to process or student behaviors as opposed to person praise. This means that teachers are more likely to promote increased student performance and an enhanced classroom environment by being sensitive to the various differences between students in relation to praise, knowing when to deploy praise, knowing how to deploy praise, and knowing that process or behavior-specific praise is more likely to produce positive results.

Praise Notes in Classroom:

The involvement and learning of students can be significantly influenced by notes of appreciation from teachers. It has been demonstrated that these messages help elementary and middle school students foster a healthy environment and reinforce the proper use of social skills. For instance, demonstrate how using teacher-written praise notes in a middle school significantly decreased the number of referrals for student disciplinary action at the institution; there was a strong inverse relationship between the quantity of praise notes distributed and the quantity of referrals for student disciplinary action. Caldarella, Christensen, Young, and Densley further demonstrate that teacher-written thank-you cards greatly reduced tardiness in an elementary school context.

Teacher-written praise notes are short written statements acknowledging desired student behaviors. They are often used to increase appropriate social behavior and to strengthen teacher-student relationships.

- Firstly;

Before implementing a praise note system at a K-12 school, it is important to train teachers about the use of praise notes and to notify parents that such a system is being considered. Teacher training might be conducted by an administrator or faculty member who has research-informed experience with utilizing praise in classroom settings and should help teachers understand how to get the most out of a praise note program. A letter to parents explaining the use of praise notes to promote proper social behaviors at school, such as respect, punctuality, and responsibility, would say something like this: To honor our students' achievements, please think about reading these messages to your son or daughter when they get home from school. Please get in touch with us whenever you have questions or issues. Letters to this effect help parents understand this habit of giving appreciation and help create a sense of community around student success. All children in a given school or class may receive praise notes, which can also be specifically designed for a chosen group of students who have shown a need for behavioral improvement.

When selecting particular pupils with persistent behavioral difficulties, such as tardiness, it is crucial to ensure that the student exhibits a clear pattern of tardiness deserving of being addressed with compliment notes rather than a propensity to arrive late occasionally during the year. Teachers and administrators should also think about whether the student will benefit from receiving praise notes because some behaviors, like tardiness, may be beyond the control of a student if he or she depends on someone else to arrive to school in the morning.

- Secondly;

participating instructors need to be aware of the kinds of actions they will be looking to commend and careful in monitoring pupils for these praise-worthy behaviors after participants in the praise notes have been identified and a letter to parents has been circulated. For instance, some students may be observed for particular tardiness difficulties, whilst others may be seen for failing to turn in work by the deadline. Teachers must create praise notes and give them to the appropriate pupils in accordance to the intended student conduct whenever a behavior deserving of praise has been determined. When a student is being watched for tardiness issues, for instance, a teacher should take note of the times the student arrives on time for class or for school in the morning and then give the kid a compliment. There are several ways to express praise. Making two 3 inch square pieces of paper with designated lines for the student's name, the date, and the teacher's name is an efficient approach to create praise notes. Also included in these messages should be a series of checkboxes that say, "Thanks for exhibiting one of the following: Respect, Responsibility, Punctuality, etc."

The letter might even bear a cheery image, like a sun that's smiling or a thumbs-up symbol. The teacher should make sure to leave space on the memo for a handwritten comment or compliment to that kid.

As an illustration, a teacher might write: "Stacy, arriving to class a few minutes early is a terrific way to demonstrate respect to everyone in the class." These assertions ought to vary (if only slightly) from note to note to avoid repetition. Depending on the targeted behavior(s) in question, praise notes may be more general in nature ("for listening intently today") or more detailed ("for arriving to 3rd period class on time today.

- Finally;

For praise notes to be effective, teachers must keep an eye on the results of this strategy. According to the studies discussed above, teachers must attest that praise is provided frequently, conditionally, and specifically in order to improve effectiveness. When pupils exhibit the required conduct, commendation notes should initially be handed to them. The frequency of the notes can then be reduced and possibly o Teachers should not focus significantly on pupils who are not consistently exhibiting the required behavior after receiving early praise notes in order to prevent potential attention-seeking behaviors. Teachers can keep a close eye on those pupils for commendable conduct if they see that some students never seem to receive commendation letters.

Further, teachers will benefit from keeping a journal that monitors praise note activity quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, teachers should record how many praise notes were distributed daily and to whom. Trends, such as when and where certain students tend to evidence desired behaviors, can be observed and used to inform future use of praise notes. Qualitative data such as recording students’ responses to receiving praise notes can help gauge the degree to which these notes are individually acknowledged and taken seriously by specific students. Teachers might ask students: “How did you feel when you received that note today?” or “Did that note make you think about the importance of coming to class on time?” Teachers should generally keep track of when desired behaviors are improving so that the praise note process can be appropriately faded out at that time.

Teachers should share the results of their praise note efforts with colleagues and administrators and seek feedback surrounding the effectiveness of implementation. Teachers may be able to share relevant information that helps in better understanding which students may need to improve certain behaviors. In addition, parents should be encouraged to celebrate praise notes with their children and share their opinions on how they think praise notes are working with administrators and teachers. This feedback will further help teachers gauge the effectiveness of their praise note practice. In the case where praise notes are not having any significant impact, teachers and administrators should carefully consider the reasons behind the lack of success and work to either create a praise note system that more aptly address student issues or decide that a different approach to student motivation needs to be pursued. As Kohn points out, alternatives to praise notes may include: giving no praise, using statements that reflect what was seen by the observer (e.g. “you put your shoes on by yourself”), or simply asking questions (e.g. “what is the hardest part of writing?”).

2. CLASSROOM DIALOG:

In the 1960s, pioneers like Barnes, Britton, and Rosen and Cazden first looked at classroom-based research to see how the caliber of teacher-student talk might affect educational outcomes. The study of teacher-student interaction attracted increased international and interdisciplinary attention in the 1980s. Such curiosity prompted researchers to investigate the success (or failure) of spoken interactions between a teacher and students in creating a base of shared understanding that supports learning.

Two key areas of interest emerged from the research of classroom interaction. The first was in the nature and importance of student collaboration in learning; the second was in dialogic teaching, a notion that Freire first proposed and Alexander later developed. This area of research has aimed to identify and support the teacher-student interactions that produce the best educational results. Although there are many distinct terminologies and meanings, there is general agreement that participants in dialogue should respectfully and appropriately acknowledge and build upon other points of view. Contributions are braided into connected, cohesive lines of investigation, fostering the development of ideas throughout time. As a result, the term "classroom dialogue" is far more specific than "chat" or "conversation," and it provides chances for active student participation and agency as students develop ideas and explicitly state their understanding and reasoning. These opportunities are specifically targeted by dialogic education toward learning through the creation of collective knowledge.

Researchers contend that professors who give open-ended questions that encourage hypothesis and investigation, as well as those who allot enough time for discussion, encourage and support group thinking. It appears that asking "contingent" questions, which are directly tied to students' contributions, is more crucial for eliciting lengthy responses from students than just asking "genuine" questions, to which teachers are clueless.

Along with cognitive aspects, dialogue also involves social and emotional components. Learners must feel safe taking risks and that their contributions are recognized. Teachers may use particular techniques, such as practicing concepts and questions in pairs or small groups, encouraging the testing of concepts using encouraging language and nonverbal cues, and gradually involving more reserved students in class discussions, to create this type of learning environment. According to research, even ordinarily silent students can contribute significantly when the conditions are right, even if a small number of students can account for the vast bulk of discourse. The learning potential for the entire class is maximized by creating chances for more egalitarian engagement. Such findings suggest that (a number of) students must actively communicate, discuss their opinions, and engage in argumentation.

Productive Forms of Dialogue:

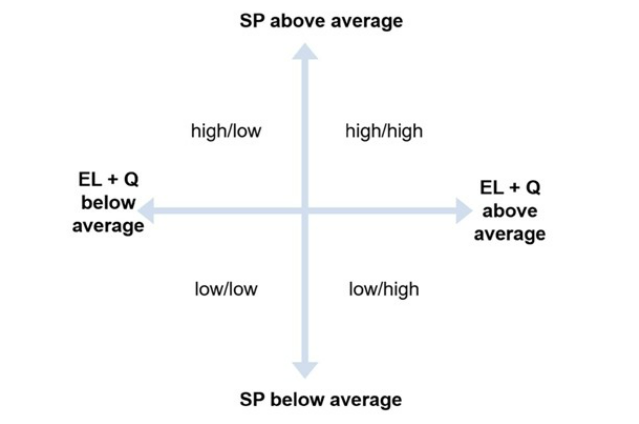

Resultantly, discourse has long been suggested to be beneficial for learning, however this has mostly been based on erroneous assumptions about the best formats. There is currently a dearth of thorough, extensive research on the particular types of student-teacher discussion and the qualities of a dialogic classroom that are linked to successful outcomes. Two recent simultaneous large-scale investigations carried out in English elementary schools are exceptions. The study by Alexander, Hardman, and Hardman showed the effects of a 20-week dialogic teaching intervention on the performance of students between the ages of 9 and 10 on standardized examinations of science, arithmetic, and English. Howe et al. looked at the connections between teacher-student interaction and various student outcomes, including academic achievement in math, science, and English (as measured by SPAG tests for reading, math, spelling, and punctuation, plus a specially designed science test), general reasoning, and educationally relevant attitudes. Two lessons from each of 72 classes in elementary schools with a variety of demographics were used as the basis for the analyses. The Cambridge Dialogue Analysis Scheme, a systematic coding framework used to classify teacher-student communication, was created by Hennessy et al. and was adapted from the Scheme for Educational Dialogue Analysis. Next, multilevel modelling was utilized to link the student outcome measures to the natural variance in the use of dialogic teaching.

Potentially complicating variables on dialogue-outcome relationships have frequently been neglected in earlier studies. 32 potentially confounding (class-level) factors were carefully measured by Howe et al (derived from meta-analyses such as Hattie). The remaining factors, such as student demographics, including SES, and features of classroom practice, including peer tutoring and technology use, were subsequently removed because only five of them were actually confounds in our context. In the end, the regression models took into account prior math and reading proficiency (mean and SD), prior student attitudes toward learning, and the standard of group projects.

Although the categories were fairly broad and might have included unproductive types of communication, the findings did provide insight into productive forms of dialogue. We chose high and low quadrants because we wanted to further investigate which elements within a category are linked to effective dialogue and how these are reflected in real-world classroom practices in classes with distinctly different degrees of discussion. This is crucial when formulating advice for practitioners. To specifically see the specifics of dialogic moves in their chronological context and, notably, in combination, we required to perform a thorough qualitative investigation. This included describing the classroom ethos that was or was not conducive for elaboration and questioning and looking at manifestations of elaboration and querying in the setting of high student participation and low student participation.

Talk-Movement Techniques and Student Participation:

Researchers closely examined the dialogic gestures made by teachers and students in the HAD and LAD lessons, focusing on those that are connected to elaboration (including inviting elaboration) and querying. As was stated in the Introduction, our large-scale study's quantitative findings showed that there were important linkages between these, student participation, and learning outcomes. Our findings are illustrated by a few transcribed episodes from the HAD and LAD lessons. Each clip was expertly transcribed from a lesson video using a portion of the Jefferson notation, which is also included in the Supplementary Material. A number of important findings are now mentioned and are best shown by one very useful instance from a mathematics lecture.

Preconditions for Productive Dialogue:

In view of the distinctions between the interactions in the HAD and LAD classrooms described above, this section highlights some prerequisites for fruitful discussion that were crucial in encouraging student participation.

Task Design and Use of Knowledge Artefacts:

Teachers in HAD classrooms designed at least some of their exercises with talk-intensive tasks. The job objective (adding cards to the number line) was made explicit, and at the same time, the standards for student contributions were defined (giving reasons for their decisions). Before beginning a discussion task, the teacher, for instance, gave preliminary instructions that included a clear objective for the discourse.

Giving the talk in these schools a defined objective framed the debates. The objectives needed to be manageable but sufficiently difficult for the discussion to be fruitful. The purpose of dialogue was either absent or poorly explained to students in LAD lessons. When instructed to "speak among yourself," students' conversations frequently veered off course.

Utilizing an artefact for collaborative knowledge creation was another crucial component of task design that promoted student participation. These types of artefacts were utilized in HAD classes; they required more than one person to write on, sketch on, or fill in information and improved pupil comparison and contrast. These items were mentioned by the students in their conversation. The ability to co-build with an item is demonstrated by the number line work in first example, which required group collaboration to annotate and complete. In many respects, the assignment created a vibrant environment for conversation. The instructor encouraged participation from a large number of pupils who spoke about their actions when placing cards on the number line.

The number line enabled for diverse concepts and changes in knowledge to emerge through modification of the cards' places, done through elaborations and querying of students' own and others' thoughts. This generated multiple opinions on where a card should be placed. This kind of manipulation of artefacts, particularly on a large display screen, can highlight the divergence or convergence of viewpoints and enable learners to express their understandings and justifications to their classmates or the instructor. Here, the opposing points of view were in fact coordinated and critiqued. Importantly, rather than concentrating on who was right, contributions were evaluated in terms of their worth for attaining the shared goal.

If another example is concerned, as the class progressed, the justification for each characteristic was added to the page, which served as a tangible resource for co-building knowledge and writing on it was in fact a purpose of the discourse. Each group was asked to list qualities of personified red blood cells. Other comparable artefacts used in HAD classes included a brief article displayed on a whiteboard, student-made posters, water cycle experiment kits, and calculations made by the teacher on the interactive whiteboard with input from many students. These items assisted the ongoing, cumulative discussion and knowledge building throughout time by making the learning histories and trajectories more evident.

In comparison, there were typically less shared objects in LAD lessons. Instead of exchanging ideas, kids focused on their own assignments, such as writing poems alone, copying and solving arithmetic problems in their own workbooks, and writing observations in their own science workbooks. Students were instructed to work in pairs, with one person reading aloud while the other drew a "map" of the readings. Even when in groups, pupils in these instances were not expected to engage much with one another; instead, teachers mostly checked individuals' progress.

Teacher-Student Dialogue; Productive for Learning:

The features of interaction in classrooms where high achievement was correlated with high levels of fruitful conversation, and vice versa, and established the prerequisites for conversation. This study information to the original large-scale study by Howe et al. that was relevant for use in practical educational settings. Our transcripts provide examples of how important conversation characteristics querying and elaboration in situations with strong student participation, which were associated with higher achievement in the initial study were actually implemented in practice. The results of a qualitative analysis demonstrated how these characteristics work together and are incorporated into meaningful, intentional interactions between teachers and students. The findings show how the more "dialogic" teachers contributed to fostering a positive, welcoming environment in the classroom conducive to dialogic learning. Many effective techniques were developed by teachers in HAD classrooms to entice more reserved pupils to engage and voice their opinions. In the HAD and LAD classrooms, students and teachers communicated significantly differently, with students contributing more and teachers speaking less, according to our studies.

High degrees of elaboration, questioning, and student interaction, according to our earlier work, were beneficial for learning because they "produced environments in which students could observe themselves think," or fostered metacognition. Here, we have identified that and shown how it might have been done. We could observe language being employed as a tool for the deliberate creation of knowledge in the HAD classrooms. Other tools also emerged as crucial; in HAD classes, student participation typically focused around an object facilitating the explicitation of thinking and knowledge co-construction. In contrast, there were less such items of mutual reference in LAD classes. As a result, there was less to discuss and less encouragement to build mutual understanding. Additionally, it seems that levels of student participation were correlated with this feature of task design. Less open-ended questions were given by teachers in LAD classrooms, and they spent more time observing and elaborating on the work of the pupils. Short, straightforward responses were the norm when their kids responded, and proactive participation was rare.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it is evident that praise can be an effective tool to motivate students if used appropriately. Specifically, teacher-written praise notes can be used to motivate younger students to employ behaviors that will increase student performance and create a more positive and engaging classroom atmosphere. When considering the use of praise in classroom environments it is important to contemplate the ways praise might have a positive or potentially harmful impact on students. This means that teachers should aim to use process praise over person praise and consider the discursive needs, interests, and experiences of students before implementing praise oriented strategies. Although the benefits of using praise to motivate students are apparent, there is research showing that teachers do not often use praise in their everyday instruction, and often are not trained how to effectively use praise in class. Further, some research indicates that students receiving process praise do not benefit significantly from students receiving no praise. And the second part of the study illustrated the value of using mixed methods in a sociocultural discourse analysis approach to the study of classroom dialogue. for example, analyzing the relative frequency of keywords such as ‘how’ and ‘because’ in turns coded querying further illuminated the differences between HAD and LAD classrooms. Teachers need to consider these findings and seek training opportunities before using praise oriented strategies. If students are not responding positively to praise, alternative avenues to acknowledge students need to be explored.

Overall, these results add to the argument that a dialogic approach to classroom instruction is appropriate. Even though the samples we have are very small, closer investigation of lessons at the two extremes of the dialogic spectrum has revealed fresh information about how dialogic teaching may aid in topic learning. These obviously affect how we practice. Our creation of the "Teacher-SEDA" tools supporting professional development and practitioner investigation into dialogic practice was influenced by the findings and numerous illustrations of fruitful and fruitless classroom interaction.

. . .

REFERENCES:

- Alexander, R. J. 2006. Towards Dialogic Teaching. York: Dialogos.

- Alexander, R. J. 2018. “Developing Dialogic Teaching: Genesis, Process, and Trial.” Research Papers in Education 33 (5): 561–598. doi:10.1080/02671522.2018.1481140.

- Alexander, R. J. 2020. A Dialogic Teaching Companion. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Caldarella, P., Christensen, L., Young, K. R., & Densley, C. (2011). Decreasing tardiness in elementary school students using teacher-written praise notes. Intervention in School & Clinic, 47(2), 104-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1053451211414186

- Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Snyder, A., Al-Hendawi, M., & Vo, A. (2009). Creating a positive classroom atmosphere: Teachers’ use of effective praise and feedback. Beyond Behavior, 18(2), 18-26.

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Caution – praise can be dangerous. In B. A. Marlowe & A.S. Canestrari (Eds.), Educational Psychology in Context: Readings for Future Teachers (pp. 207-217). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Haimovitz, K., & Henderlong-Corpus, J. (2011). Effects of person versus process praise on student motivation: Stability and change in emerging adulthood. Educational Psychology, 31(5), 595-609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2011.585950

- Haydon, T., & Musti-Rao, S. (2011). Effective use of behavior-specific praise: A middle school case study. Beyond Behavior, 20(2), 31-39.

- Hattie, J. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hennessy, S. 2011. “The Role of Digital Artefacts on the Interactive Whiteboard in Mediating Dialogic Teaching and Learning.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 27 (6): 463–586. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00416.x.

- Kohn, A. (1996). Five reasons to stop saying “good job!” In B. A. Marlowe & A.S. Canestrari (Eds.), Educational Psychology in Context: Readings for Future Teachers (pp. 200-205). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Maclellan, E. (2005, November). Academic achievement: The role of praise in motivating students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 6(3), 194-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/ 1469787405057750

- Mercer, N., and L. Dawes. 2014. “The Study of Talk between Teachers and Students, from the 1970s until the 2010s.” Oxford Review of Education 40 (4): 430–445. doi:10.1080/03054985.2014.934087.

- Nelson, J. A. P., Young, B. J., Young, E. L., & Cox, G. (2010). Using teacher-written praise notes to promote a positive environment in a middle school. Preventing School Failure, 54(2), 119-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10459880903217895

- Partin, T. C. M., Robertson, R. E., Maggin, D. M., Oliver, R. M., & Wehby, J. H. (2010). Using teacher praise and opportunities to respond to promote appropriate student behavior. Preventing School Behavior, 54(3), 172-178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10459880903493179.

- Sedova, K., M. Sedlacek, R. Svaricek, M. Majcik, J. Navratilova, A. Drexlerova, J. Kychler, and Z. Salamounova. 2019. “Do Those Who Talk More Learn More? The Relationship between Student Classroom Talk and Student Achievement.” Learning and Instruction 63: 101217–101217. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101217.

- Skipper, Y., & Douglas, K. (2012, June). Is no praise good praise? Effects of positive feedback on children's and university students' responses to subsequent failures. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(2), 327-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279. 2011.02028.x

- Wheatley, R. K., West, R. P., Charlton, C. T., Sanders, R. B., Smith, T. G., & Taylor, M. J. (2009). Improving behavior through differential reinforcement: A praise note system for elementary school students. Education and Treatment of Children, 32(4), 551-571.

- Wilkinson, I. A. G., A. Reznitskaya, K. Bourdage, J. Oyler, M. Glina, R. Drewry, M. Kim, and K. Nelson. 2017. “Toward a More Dialogic Pedagogy: changing Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices through Professional Development in Language Arts Classrooms.” Language and Education 31 (1): 65–82. doi:10.1080/09500782.2016.1230129.