Image by Pavan / Lamayuru: shot on canon d3000

“The goal of modernity is to free ourselves from our past and from the law of nature!”

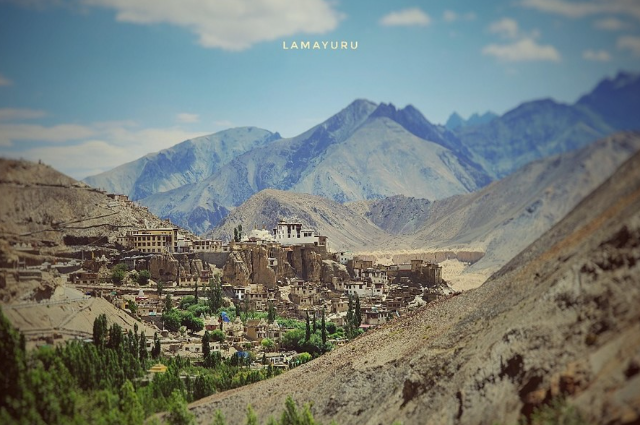

This unique place is well known across the world for its lunar landscape. The scars, curves, edges, and snake-like cliffs that look like a spread-out-dissected-brain, glistening with a tint of lime-yellow on a bright sunny day, make it so marvelous that one wishes to jump around and float in midair, as if in a simulation of the Moon. Unfortunately, it’s still Earth- and gravity is still at business, and the place is Lamayuru in Ladakh. The monastery that stands on the tip of a mountain offers a view worth gazing at for hours. The maroon edges of the roof catch the eyes of passersby, and the homes below blend so well that one can imagine the whole place to be an anthill, with humans crawling like termites.

It was late in the evening when my Bullet 350 climbed to the top and halted at the entrance in front of a red gate. I immediately got the last ticket to the monastery, and before I handed the money to the monk, who was sitting under a restless ceiling fan, I asked what the money was used for. He smiled, revealing his bright yellow teeth, and said urgently, "For the development of the monastery!" I nodded, said "Julley," and moved on thinking “what more development, everything looks new!”

As an amateur portrait photographer, I was eager to find some interesting faces to capture. My camera called for action, but there were very few people around. Maybe it was because it was getting late, around 6:30 PM, but Ladakh, being at a high altitude, doesn’t see sunset until around 8 PM. I roamed around the monastery, unable to figure out the entrance to the many windowed world that peeked out from all directions. I finally found it, but just as I was about to step in, I was warned that the monastery was about to close. I hurried inside, and like any other monastery, I noticed the enormous spillage of money, biscuits, juice, dry nuts, and various other offerings. I was puzzled.

How could these west originated products, filled with unwanted sugar and unregulated substances—the ultimate products of modernity’s illnesses—were the metaphor for devotion? Perhaps it’s a devotee’s way of offering. Maybe it’s their helplessness in finding the right thing at the right time. But the truth stands: capitalism is permeating our devotion. I left the monastery after a kind monk, who was performing his evening rituals- cleaning utensils and washing photos and idols, handed me an apricot. We exchanged a few words about the health of the Dalai Lama before I moved on and stepped out with uncontrolled craving for the special fruit.

The wind was calm, but my camera was still empty of faces. I took a photo of myself with a timer, and at that moment, an old woman slowly walked by, a prayer wheel in her hand and mantras on her lips. Her face was deeply wrinkled, her clothes crumpled from the weight of the basket on her back. Her pinkish cap revealed her ears, and her hair was tousled. I smiled at her and said "Julley" in an enthusiastic tone, excited and ready to capture her face in an interesting expression. But instead of snapping the photo spontaneously, I decided to ask for her permission.

“Achi!!! Can I take your photo?” I asked calmly.

She paused for a moment, looked at me and my eager camera, and asked, “Paisa dega?” (Will you pay me?)

“No,” I replied instantly.

She grunted with a disappointed expression and turned to walk away. I was angry, and my hands itched to press the shutter button.

“Achi!”(Sister) I cried out like I was in sudden shock, and the old woman turned half of her body and the photons were frozen for eternity making her immortal. I was satisfied, but her face fell like a melted wax as she walked away.

Grandma who asked for money / Image by Pavan

This type of incident- where an elderly asks for money in return for a photo, was not an isolated one. Many individuals before and after demanded cash like an eager kid asking for candy. It’s not that these elderly people are so privacy-conscious that they fear their photos might be misused on social media. The fact remains that they don’t care much about what happens online, and many barely know about the virtual world of Instagram. So, what made them ask for money? This question might seem trivial and insignificant, but the reasons and implications it brings to light are troubling.

People in India are fond of the mountains; they attract more tourists than beaches and temples combined. The mountains offer peace and tranquility in contrast to the hustle and bustle of daily city life. As for the people living in the mountains, they are often thought to be the happiest, blessed with fresh air, sunshine, greenery, and clear water. If they have all the things city dwellers can only dream of, why do they crave material money from visitors? Aren’t they really happy there? What does money have to do with a simple photograph that takes only a moment of their lives? And why would the elderly, who are presumed to be more attuned to spirituality than materialism, ask for it?

As I tried to investigate, I was disappointed to discover that the answer wasn’t straightforward. Even I, as a traveler, was likely a contributing factor to this shift in their mindset.

Progress could be Painful

A rare picture of progress trying to fit in traditional life / Image by Pavan

There is no denying that without progress, we would still be primates, scavenging the marrow of dead animals in the jungle, unsure of the reason behind thunder and lightning attributing it to imaginary gods shaped like rocks and streams of rivers. Today, we have everything we could only imagine a few years ago, and we are so taken away by the tide that none of us paused for a moment to introspect on how progress is necessary to keep us sane. The invention of the wheel revolutionized transportation, the light bulb gave us an edge over the darkness of night, the telephone enhanced our ability to communicate over distances, and money made these innovations available at our doorsteps.

We have progressed so much that we can no longer distinguish ourselves as humans. Instead, we have become organic machines, our intellect entirely invested in generating money for a future which we fear every day. There’s also a common agreement that there’s no going back now, and progress—like a greedy human—is unknowingly demanding more and more sacrifice from us. Until now none can agree that the invention of all these technological gadgets has given us more free time. [1] Instead, it has made us more miserable in increasingly unhealthy ways.

The pride of an average human now comes from being busy; watching the clouds drift by is considered either the behavior of a madman or the burden of a paralyzed patient. A slow life has become a luxury that one must pay for in today’s hyper-busy world.

Before I talk about the changing psychology of elderly in a newly opened world of Ladakh, I have to stress the following point to give a grand context to what I am trying to prove.

We consider GDP to be a hallmark indicator of growth and progress, but little do we realize that a car accident, which hospitalizes a man and leaves him suffering in a crowded ward, contributes more to GDP than a man who rides a bicycle and remains healthy throughout his life. The numbers indicating growth can bring out a strange patriotic in our minds, calling ourselves an unstoppable economy. As a common citizen with regular education, we are made to believe that economy is driven by numbers where we fail to account that there are human lives that matter more than mere numbers.

All that the government cares about are the transaction of currency from one hand to another generating taxes. Consumption and production are prioritized over meditation and observation. The surge of tourism, like a hot wind blowing through a narrow tunnel, brought a devilish money mindset to these once-pious souls, whose routines began and ended with “Om Mani Padme Hum.”.

I am not blaming growth and as far as I can see, growth enabled a lot of things that make up my life way better and I would be at a loss without it. But, relying only on growth is one of the stupidest purpose ever invented by any culture.

“We’ve got to have enough; growth of what, and why and for whom and who pays the cost and how long can it last and the what’s the cost to the planet and community and how much is enough?” asks Kate Raworth, the author of Doughnut Economics- whose retake on basic assumptions of economy is changing the field of economics. [2]

When tourists arrive—like me—they don’t come empty-handed. They carry their lifestyle like the scent of perfume. Perhaps the camera in my hand influenced the grandma to ask for money. Maybe it was my worn-out torn jeans or my green mountain boots, which were foreign to her triggering her inferiority. What they don’t realize is that I am both advanced and miserable at the same time. Progress is merely the measurement of how many material goods one can access, but it is not the measure of the quality of life one can attain. In short, progress does not equate to human happiness, and happiness is not even a parameter in our daily calculations of GDP or GNP. This misconception is ruining the peaceful minds, binding them to an imaginary carrot that they can never reach, perpetuating endless unhappiness. As Alfred Marshall, in his influential book Principles of Economics puts it, “Human wants and desires are countless in number and very various in kind. The uncivilized man indeed has not many more that the brute animal; but every step in his progress upwards increases the variety of his needs…he desires a greater choice of things, and things that will satisfy new wants growing up in him”

I could never make the grandma to digest the fact that she held the precious gift of nature beside her home and I travelled around three thousand kilometers from Bangalore to watch her chant mantras. All she knew was that progress meant good clothes and flashy gadgets.

Spirituality to Stupidity

It was getting late. The sun had sunk behind the creamy layers of mountains, and the wind was growing chilly. The children were gathering their leftover toys from the streets and heading inside their homes. The monks were closing the gates to tourists, and I had finished exploring the village of Korzok. It had been a hectic day, as I had ridden my bike from Leh to Korzok for more than six hours, stopping en-route at Puga Valley. The road was still unpaved, with rocks jutting out like bubbles on foam. I feared falling because if I did, there was little hope of help; very few people traveled that route. The bike was heavy, and it would have been impossible for me to lift it on my own. Fortunately, my worst fears didn’t come true, but the mental toll was high. I craved rest like a man recovering from a severe hunger.

As I made my way to my homestay, I happened to stumble upon a doctor named Prasanna Jit Jain from Kolkata. He was conversing with some elderly locals on a muddy terrace. For some reason—perhaps it was the confusion and exhaustion on my face—he called out to me.

“Come, have some milk!” He was familiar with visitors to the village, almost like a local, having served in the village for three years.

He was giving medicine to an elderly lady in a red sweater that looked like a layer of hair on her skin. Her face was wrinkled at every inch, and she was basking in the last sunlight of the day. Her calm demeanor and sweet voice welcomed me as I climbed up to the terrace. “Julley!” she said. I had become so used to the word that I repeated it to everyone, sometimes even to strangers on the street, just for fun.

I struck up a conversation, and the elderly lady brought me the milk.

“Thuk-je-che,” I said (thank you).

She smiled, clearly pleased with my efforts to speak Ladakhi. The doctor told me she was the oldest woman in the village, though she didn’t appear that old to justify his statement. Still, I nodded and, out of curiosity, asked,

“Now that you’re here, what did people do when there were no doctors? How were they treated?”

The doctor smiled and answered in a reassuring voice,

“I’ve been here for three years. I used to have breathing problems, and kidney stones would come and go like clouds back in Kolkata. The pure air, fresh glacier water, and serene peace have literally healed me without any medication. Now, tell me, do you think these people get sick?”

I thought the doctor was exaggerating.

“There must be some illness! How can there be a place where no one gets sick?”

“Have you seen their toilets?” he asked, raising an eyebrow.

“Yes,” I replied.

“You might have noticed that they’re placed right in front of the house?”

“Yes, I recall that.”

“Even though they are waterless toilets, where the waste falls into a heap that is then covered with ash, there’s no concept of bacteria here. This place is so pure. As for sickness... yes, there have been and will always be diseases. But the way medicine is practiced here is different from the past.”

Cheers to the oldest person at Korzok / Image by Pavan

I was intrigued and was eager to learn more. The doctor mentioned a book called Ancient Futures: Learnings from Ladakh by Helena Norberg-Hodge which I grabbed instantly after returning to Leh. Helena Norberg-Hodge is a Swedish-born author, filmmaker, and prominent environmental activist known for her advocacy of localism, sustainable development, and the preservation of indigenous cultures. She is best known for her work in Ladakh. The book was like a revelation to me- a mind-blowing experience that made me realize that the Ladakh is a planet of its own with its own practices and livelihood unlike another. [4]

The author explained that “Illness is not seen as a malfunctioning of a particular part of the body, but as a general imbalance. Disorders are viewed from a broader perspective, with body, mind, and spirit recognized as integral parts of the same entity.”

As tourists, people are often drawn to the scenery to capture better photographs, but not the people and their way of life. Yet the real charm and magic of a place comes from its people. We see the material side of the culture—worn-out clothes, animals pulling a plow, vast stretches of empty land—but not the peace of mind or the strength of family and community. The psychological, social, and spiritual wealth of the Ladakhi people often goes unseen.

As for that old lady in the village, don’t assume she is no longer an active participant in village life. For the elderly in Ladakh, there are no fears of being left alone or unwanted. They remain important until they die. In contrast, the dominant thinking in Western society has molded us to believe in the unworthy argument that we are inherently aggressive, locked in a perpetual Darwinian struggle. But if you watch these people move, you will discover the true treasure of a slow-paced life.

Slowness gives the mind time to reflect on the surroundings. They are mindful—chanting mantras, looking at others with compassion, smiling at strangers, and enjoying healthy homegrown meals. The failure to appreciate this comes from our inability to distinguish between natural evolution and the changes wrought by the scientific revolution. While the West thrived with industrialization, much of the world continued at its own pace. Yet we are led to believe that a slow life is primitive and less evolved.

But it’s not just us. Even the Ladakhis are on the same path toward folly. They are building modern flush toilets, raising double-story buildings with cement, calling for large vehicles for transportation, ceaselessly counting money, and calling themselves rich—forgetting that they are leaving behind the value of their past. Pollution and overpopulation are no longer considered in a locality while building something or buying a new vehicle. Polyandry was once practiced keeping the population in check. Yes, it did has its downsides but its just a perspective. Roads were rough, but pollution was minimal. The water was pure, but now they drink sugary packaged drinks. Men go out to work, but in the past, they actively participated in raising children like mothers did giving a full-fledged family tie to a newborn. Masculinity was not threatened by nurturing—it embraced it. The arrival of James Bond and Sholay has changed their entire worldview. They now smoke foreign cigarettes and drink strong alcohol instead of local chang.

I’m not suggesting that all these changes are inherently bad. Things change, cultures evolve, and people adapt. But I question the pace of change, which is turning spiritual people into sheeps running towards modernity.

Buddhism to Black Glasses

Monk resting near Stok gompa / Image by Pavan

“They see life and death as two aspects of an ever-returning process. Theirs is a culture that has come to terms with death, and this attitude is one of profound acceptance of inevitable change. Thus, even a traumatic event such as the death of a baby can have a different significance.” - Helena Norberg-Hodge

When you visit any village, whether large or small, or even just a locality with three or four homes, you will notice the white arches at the entrance of each hamlet beside the road. These arches, resembling small creature dwellings lined up like spikes, are called chortens. What intrigued me the most was the sun and moon-like structures attached to the top of each arch. I understood the basic reason for their placement—to ward off evil forces from entering the hamlet—but the sun and moon had a deeper significance rooted in Buddhist philosophy.

The Buddhist concept of interconnectedness, or pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), is a profound treasure in Buddha’s teachings. Everything in this world is interrelated, and so are the sun and the moon. Chortens symbolize the oneness of life, the cessation of duality[5]. This symbolism doesn’t end with chortens in Buddhism. I also observed three arches built around every monastery and palace: orange, blue, and white. Upon further exploration, I learned that the orange arch represents wisdom, the blue symbolizes strength, and the white stands for compassion. Even biological differences are imbued with meaning: women symbolize wisdom, and men, compassion. Together, they form the essence of the religion.

Chortens: Stok village / Image by Pavan

I was discussing this with a monk the day I visited the Korzok monastery. He spoke fluent English, and every word he uttered carried weight, as if he had carefully considered each syllable. “Those who believe in existence are stupid like cattle, but those who believe in non-existence are still more stupid. Things are not existent, not non-existent. Not both, and not something that is not both,” he said. I was stunned. I felt as though I understood his words, but truthfully, I couldn’t explain their meaning. It was like trying to describe the color red to a blind person—you know it, you see it, and you feel it, but you can’t put it into words.

Deities and philosophy of Buddhism as paintings / Image by Pavan

Ladakh, with its harsh weather and unforgiving terrain, might never have welcomed human life if not for the Buddhist way of living—a life of self-sustenance and harmony with nature. Their culture reflects fundamental human needs while respecting the natural limits. It’s like saying that joy and peace of mind were their birthrights until greed and the market economy invaded their consciousness.

The monasteries now have well-paved roads. The colors are bright and polished. The idols inside the temples gleam like gold, and there is money everywhere. As I mentioned earlier, I continue to observe the shift in monks’ perspectives on life. I may be completely wrong in my views, limited by my short stay for two months and perhaps unaware of the full picture, but my rational mind compels me to express my observations, even at the risk of ridicule.

In the past, the youngest son of each family was often forced to become a monk. He had no choice but to study religion and serve the community. The villagers funded the monasteries, and in return, they received wisdom and knowledge. The teachings were perceived by the young monk at the cost of celibacy, which was considered meaningful and noble. This tradition persisted for a long time, but as times changed, perhaps due to the influence of human rights advocates or inner desires for freedom, monks can now choose to leave monastic life and return to family life whenever they wish.

[6]Before Ladakh opened to tourism in 1974, it had very little connection to the outside world. The high mountain passes, often snowbound, restricted movement from the Kashmir Valley, and the harsh Himalayas deterred invaders from the other side. While military presence was a reality, it did not expose the people of Ladakh to Western ideas and products. Even today, some villages are so remote and isolated that electricity is still a luxury. When modern, fancy products suddenly poured into the region, the people were overwhelmed by the allure of these shiny new objects. This temptation didn’t stop with the general public; even the monks, who spent most of their time in meditation, were drawn into the flux.

As I climbed the steep stairs of Spituk Monastery, my legs shook under the weight of the incline. The wind was calm, but the sunlight was intense- harsh enough to burn the skin. The sunglasses I had brought with me were a relief, and the sunscreen felt like a lifesaver. Just as I was about to step inside the monastery, a monk in his mid-thirties walked out. He wore a Puma jacket over a fancy maroon t-shirt, Ray-Ban sunglasses dangling from his chest, and Adidas shoes that looked more authentic than mine. It didn’t take long for me to realize that alongside Buddhist texts, there was room for Boomer chewing gum in their mouths. And so the story goes. Aside from the people, the idols, and the buildings, little remains of Buddhism in outlook.

The ability to adapt to any situation and find happiness despite circumstances is an incredible strength, but this very strength is becoming a vulnerability. I am not a Buddhist myself, but I was always fascinated by their practical foundation and usability of their principles. Buddha, himself asked his followers to introspect before accepting something into their lives. I practiced vipassana and it is indeed one of the richest experiences of my life.

In my view, integrating modern objects into a spiritual life is leading to distraction and detachment from the core values of Buddhism. There’s little I can to do to stop it but believe in cultures to protect their core values.

The Land of High Passes to Mountain Markets

The farmers once produced only what they needed, stored enough for the winter, used dzo to pull the plough, relied on glacier water to nourish the land, and worked with family members to harvest- singing together as they went. It sounds like an ideal life, and trust me, it was a happy place to be. You would wake up to the sight of massive mountains stretching across the horizon, their peaks capped in white. You'd greet an elder with a smile as you walked to your fields. The local doctor would be there to tend to any injuries or illnesses. Little money exchanged hands, and everything you needed for a happy life was already within your mind, body, and soul—until modernity arrived with a spear to pierce that trinity.

Development is often just a euphemism for exploitation, a new kind of colonialism. If you are self-sustained—growing your own crops, using solar panels, making your own medicine—there's no need for government officials to come around collecting taxes. The system doesn’t like that. They never let you remain self-sufficient, and if you do achieve harmony with yourself and nature, you're labeled as primitive, uneducated, and ignorant—someone incapable of participating in modern society.

As a result of this misconception farmers are growing crops for markets they don’t understand and for people they don’t know. The focus of progress is not on human welfare but on commercial gain. European yardsticks of development are applied everywhere, pulling diverse people from rural areas into large urban centers, where power and decision-making are concentrated in the hands of a few. In these centers, job opportunities are scarce, community ties are severed, and competition intensifies drastically. The Western education system impoverishes us all by teaching people worldwide to depend on the same resources, while neglecting the riches of their own environments.

The modern Ladakhi school teaches them about the world far away neglecting the local ecosystem and its preservation for the better future. Their slow-paced, peaceful lives have been shattered, and time itself has been transformed into a commodity—something that can be bought and sold.

A Ladakhi student going to school to study things totally irrelevant to her ecology. / Image by Pavan

I personally believe this cultural shift began when we started feeling inferior to the Westerners, who compared us not with their actual society but with their idealized vision of it. “Some might blame capitalism for this transformation, but I don’t think it matters which system we adopt—whether capitalism, communism, or socialism—because all of these post-industrial ideologies focus on the distribution of resources, disconnecting people from the rest of creation. All these arrogant systems assume that natural resources can be stretched indefinitely.” Says Helena Norberg-Hodge and continues, “It really angers me how we city dwellers talk about nature, its greatness and beauty, all the while keeping plants in plastic pots and hanging pictures of trees on our walls.” As we acquire and earn more, we don’t gain a sense of belonging—instead, we foster competition, division, and envy.

Today, Ladakh is a heaven for bikers, backpackers, tourists, wildlife enthusiasts, mountaineers, explorers and environmentalists. Everyone loves to ride a bike amid the vast expanse of Himalayas and it’s a dream come to true for many around the world. The slow tourism with tourists getting involved in daily life of a Ladakhi needs a lot of attention so that everyone travelling to that majestic convergence of continental plates will understand the real significance of simple things that make a life beautiful. I have travelled across India and trust me, Ladakh is one of the most beautiful places in India and on earth. The people are simply gold with their heart and soul. They treat you like you are one of their own and I believe that it is not just because of money that tourism brings, they still preserve their inner kindness and compassion from the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism.

If you visit Ladakh, please make sure to blend in and experience their rich culture by consuming and encouraging the local cuisine, clothes and modes of transportation instead of directly relying on modern sugary coated foods and puffer jackets.

To end on an ironic note, here’s an interesting fact: there is no Ladakhi word to express the Western obsession with an exclusive, passionate, romantic attachment. In other words, there is no word for love in Ladakhi. Yet they still are the happiest and loving people I have ever seen.

. . .

Citations:

- Turkle, Sherry - Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (2011).

- Raworth, Kate. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017.

- Marshall, Alfred. Principles of Economics. 8th ed., Macmillan, 1920.

- Norberg-Hodge, H. (1991). Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. Sierra Club Books.

- Hanh, T. N. (1998). The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching. Broadway Books.

- Rizvi, J. (1996). Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.