Introduction: The Wave of Change Across West Africa

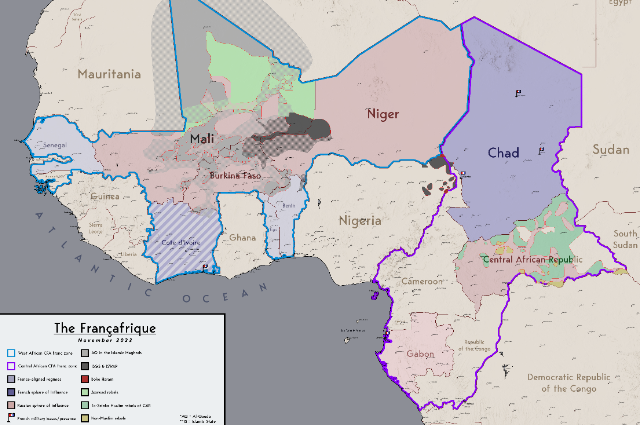

A revolutionary transformation is sweeping across West Africa, challenging centuries of French colonial dominance and neocolonial control. Since 2020, a series of military transitions has fundamentally altered the political landscape of the region, with Niger experiencing a coup in July 2023, Gabon ending the 55-year Bongo dynasty in August 2023, Mali continuing under military leadership since 2020, and Burkina Faso under Captain Ibrahim Traoré since September 2022. These changes represent far more than simple power transfers – they constitute a coordinated rejection of Western-imposed governance structures and economic exploitation.

The common thread binding these movements together is an unprecedented level of anti-French sentiment and the systematic dismantling of neocolonial structures that have persisted since formal independence. Across the region, French military forces have been expelled, French media outlets suspended, and military cooperation agreements dating back to independence terminated. This coordinated resistance suggests not isolated incidents but rather the emergence of a genuine sovereignty movement that threatens to reshape Africa's relationship with its former colonial masters.

Africa's current awakening represents the beginning of the end of France's neoliberal dominance and the emergence of genuine sovereignty movements across the continent. The implications extend far beyond West Africa, as these developments challenge the entire framework of post-colonial dependency that has characterized Franco-African relations for over six decades.

The Bongo Dynasty Falls: Gabon's 55-Year Reign Ends

The Bongo family's 56-year rule in Gabon, backed by France, exemplified enduring authoritarianism in Africa. From Omar Bongo's 1967 rise to his son Ali Bongo's 2023 fall, the dynasty accumulated vast wealth, with investigations uncovering about €100 million in French assets. Despite Gabon's $1 billion annual oil revenue and a per capita GDP of $18,000 (PPP), roughly a third of the population lived in poverty, with 37% youth unemployment. This stark contrast highlighted the neocolonial extraction model benefiting elites and foreign entities rather than the populace.

The August 2023 military coup that ousted Ali Bongo was celebrated domestically but condemned by the West. This divergence underscored the gap between local experiences of corruption and international perceptions of governance. The coup leaders, unlike other Sahel nations, did not expel French troops but lifted bans on French media. The West's restrained response reflected the coup's strategic nature and the Bongo regime's unsustainable corruption. However, the popular support for change mirrored broader regional trends against neocolonialism, driven by grievances over corruption, inequality, and foreign domination.

Niger: The Humanitarian Crisis of Sanctions

The July 26, 2023 coup in Niger prompted severe sanctions from ECOWAS, backed by the EU and France, targeting the world's second-poorest nation where over 50% live on less than $2.15 daily. Sanctions included border closures, financial transaction suspensions, asset freezes, and cut off the power supply from Nigeria, which supplied 70% of Niger's power. Despite warnings of catastrophic humanitarian consequences, the EU prepared for additional sanctions, exposing the discrepancy between Western strategic interests and claims of prioritizing human rights.

The sanctions immediate impact was devastating. In Niger, where 4.5 million relied on humanitarian aid, assistance was blocked. Power cuts affected hospitals, leading to reported deaths of babies in incubators due to electricity shortages. Food shortages worsened as borders closed, pushing populations toward famine. The World Food Programme warned of a humanitarian catastrophe exceeding the coup's direct impacts, revealing the moral issues of economic warfare against civilians for political goals. Existing vulnerabilities like food insecurity and limited healthcare were exacerbated, illustrating how international law and humanitarian principles could be secondary to geopolitical interests when African sovereignty challenged Western control.

Regionally, ECOWAS faced increasing opposition to military intervention. The Nigerian Senate, religious institutions, and even President Tinubu's party members opposed military action, reflecting broader regional scepticism. Algeria mediated, proposing a 6-month transition plan, leading ECOWAS to offer a 9-month transition, indicating a shift from their initial hardline stance. Mass protests in Niamey supporting the military government showed potential resistance to external intervention, highlighting the illegitimacy and risks of military solutions. The inability to achieve consensus on intervention marked a significant change in regional dynamics, signalling the emergence of alternative arrangements and the decline of French influence in the Sahel.

The Myth of Western Aid: Pennies for Pounds

Western aid to Niger is grossly inadequate. In 2021, it amounted to $71 per person annually—just $1.37 a week, with a mere 7 cents for education and 15 cents for healthcare weekly. This aid, mostly survival-focused, does little to drive development. The $1.8 billion total, while seemingly large, has minimal per-person impact, exposing aid as largely symbolic, maintaining political ties and justifying resource extraction over addressing real needs.

Donor aid analysis shows similar inadequacies. In 2022, France provided $5.26 per person annually, Germany $2.63, the EU $20, and the US $9.32. These figures fall far short of the $272 billion annual gap to meet UN Sustainable Development Goals. The disparity between aid and resource extraction, like France getting 80% of its uranium from Niger while giving minimal aid, highlights the neocolonial model where extraction far exceeds investment.

Aid often serves to maintain political relationships, justify resource extraction, and provide moral cover for policies that perpetuate underdevelopment. Its focus on emergency assistance rather than structural investment ensures dependency. This failure to catalyse development fuels African scepticism towards Western aid and sparks interest in alternative economic partnerships.

The CFA Franc: France's Economic Stranglehold

The CFA Franc system, controlling the currencies of 14 African nations through WAEMU and CEMAC, epitomizes neocolonialism. Despite formal independence, these countries lack monetary sovereignty, with currencies pegged to the Euro and managed by France. Key control mechanisms include depositing 50% of foreign reserves with the French Treasury at low interest rates and one-way currency convertibility from CFA to Euro, favouring European investors.

This system creates barriers to African development by preventing currency devaluation to boost exports, forcing low wages for competitiveness, and draining investment capital through risk-free capital flight. African governments cannot implement independent monetary policies to address crises or stimulate growth, remaining dependent on foreign aid.

Statistically, CFA Franc zone countries are disproportionately underdeveloped. Approximately half of the nations in the bottom half of the UN Human Development Index are CFA members, despite being only 8% of the global population. Countries like Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso rank among the poorest globally despite resource wealth. This evidence supports the argument that the CFA system facilitates resource extraction rather than development, keeping African wealth flowing to Europe while populations remain in poverty.

Captain Ibrahim Traoré: The New Sankara

Captain Ibrahim Traoré's emergence as Burkina Faso's leader at age 35 represents a generational shift in African leadership. Born in 1988, one year after Thomas Sankara's assassination, Traoré grew up during the pro-Western rule of Blaise Compaoré but chose military service over emigration or political accommodation. His experience in Sahel counter-insurgency operations, particularly in regions where French forces were present but civilian protection remained inadequate, shaped his understanding of foreign military intervention as serving strategic rather than humanitarian purposes.

Traoré's September 2022 coup against Lieutenant Colonel Damiba was framed as a "rectification" rather than a simple power grab. Damiba's failure to break with France despite promising change had disillusioned military officers and civilians alike. The median African age of 19 years makes Traoré's youth an asset rather than liability, as he represents the aspirations of a continent where most people have no memory of independence struggles but face daily realities of continued foreign domination.

Unlike many African leaders who emerge from political or business elites, Traoré's military background and modest origins provide credibility with ordinary citizens. His retention of the simple rank of "Captain" rather than adopting grandiose titles signals continuity with Sankara's egalitarian approach. This symbolic choice resonates powerfully in a region where leadership style often reflects deeper philosophical commitments about governance and development.

Revolutionary Policies Echoing Thomas Sankara

Traoré's development agenda explicitly channels Sankara's vision of self-reliant African development. The government has set ambitious targets including creating one million jobs within the next few years, providing 100,000 solar-powered water pumps to rural areas, and investing $250 million in maternal healthcare by 2025. Plans to electrify 605 localities and spend $150 million on agricultural inputs directly address the rural poverty that affects most Burkinabé citizens.

The tomato processing initiative exemplifies Traoré's approach to value-added development. Rather than exporting raw tomatoes, Burkina Faso is developing three processing plants to produce finished goods for both domestic consumption and export. This strategy of moving up value chains reflects Sankara's emphasis on processing raw materials domestically rather than serving as a supplier of unprocessed commodities to former colonial powers.

Mining sector reforms demonstrate Traoré's commitment to resource sovereignty. The government has changed mining codes to redirect royalties directly into development projects while establishing new state mining entities to increase national control over gold production. The creation of the APEC (Agence pour la Promotion de l'Entrepreneuriat Communautaire) crowdfunding system allows citizens to invest directly in development projects, creating domestic ownership of industrialization processes.

Comparison with Other Military Leaders

Among recent Sahel military leaders, Traoré has articulated the most comprehensive development discourse. While Mali has successfully renegotiated mining contracts to generate an additional $820 million annually in government revenue, and Guinea has made some progress on infrastructure, Burkina Faso under Traoré has presented the most systematic alternative to Western development models. The government's focus on domestic resource mobilization through APEC represents an innovative approach to development financing that reduces dependence on foreign aid and investment.

The contrast becomes apparent when examining policy depth and popular engagement. Mali's transitional government has maintained agreements with trade unions and implemented some wage increases, but the approach remains largely within conventional parameters. Guinea's direction appears more ambiguous, with limited movement beyond contract renegotiations. Niger's transition is too recent for comprehensive evaluation, though early signals suggest alignment with the broader anti-French trajectory.

Traoré's emphasis on citizen participation through mechanisms like APEC and volunteer defence forces distinguishes his approach from more traditional military governance. The recruitment of over 50,000 civilians into volunteer defence units demonstrates popular support while creating alternative security structures independent of foreign military assistance. This combination of economic nationalism and popular mobilization most closely resembles Sankara's revolutionary methodology adapted to contemporary conditions.

The Broader African Awakening

The Alliance of Sahel States (AES), formed by Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso in September 2023, challenges Western regional influence. Initially a defence pact, it now aims for economic integration, including a common market and currency independent of the CFA system. The AES reflects a Pan-African vision, with members expelling French forces, ending colonial agreements, and pursuing resource sovereignty. Positive GDP growth projections for 2024 highlight its potential for independent development.

The expulsion of French forces marks the end of six decades of military neocolonialism. Despite Western counterterrorism arguments, Sahel states prioritized sovereignty, replacing French forces with partnerships from Russia, China, and Turkey. These new partnerships offer security and development aid without the conditionality of Western assistance, providing African nations with greater autonomy and negotiating power. This shift reflects African frustration with Western paternalism and signals a move toward multipolarity in international relations.

The French Response: Panic and Adaptation

France's withdrawal from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger marks a significant reduction in its military presence in Africa, undermining its rapid intervention capacity and global power claims. This loss forces France to rely more on economic and diplomatic control, which also face growing African resistance. The strategic implications extend globally, as France's diminished influence may reduce its value as a Western security partner.

Economically, France faces challenges from suspended mining operations and African resource nationalism, threatening profits and supply security, especially for uranium. The CFA Franc system's credibility is also at risk, with AES countries exploring monetary independence, potentially reducing French financial benefits.

Diplomatically, France has scrambled to counter African resistance through EU sanctions and media campaigns aiming to isolate Sahel governments. However, these efforts risk undermining European soft power and have shown limited effectiveness. France's attempts to address historical grievances, like declassifying Sankara assassination documents, have been inadequate, indicating a reactive rather than strategic approach to adapting to new realities.

Thomas Sankara's Enduring Legacy

Thomas Sankara's brief presidency in Burkina Faso set a precedent for authentic African independence, inspiring current leaders. He prioritized national self-reliance, rejected foreign debt, and focused on rural development, proving alternative development paths viable. His anti-imperialist stance challenged French control, and his policies led to significant improvements in healthcare, education, and agriculture. Sankara's vision resonated internationally, influencing African youth and resistance movements. His 1987 assassination by Blaise Compaoré ended the revolution and restored French influence. Compaoré reversed Sankara's policies and suppressed his legacy. Evidence suggests French involvement in the assassination. Ibrahim Traoré, who draws parallels with Sankara in background and vision, is seen as his ideological heir. Traoré's policies, like youth mobilization and resource nationalism, echo Sankara's methods. The construction of the Thomas Sankara Memorial under Traoré's leadership symbolizes a commitment to Sankara's legacy and principles.

The Regional Domino Effect

The success of military transitions in the Sahel has caused fear among pro-Western African leaders. Cameroon's Paul Biya quickly reshuffled military leadership after the Gabon coup. This shows that regime change could spread beyond the Sahel. The failure of Western threats to restore old governments has made opposition forces bolder. ECOWAS's inability to carry out military intervention in Niger, despite having Western backing, has shown the limits of external force. This encourages other African movements to challenge unpopular governments without fearing automatic Western intervention.

African governments are under increasing pressure to adopt policies like those of Sahel nations against foreign corporations and military forces. Trade union movements in countries like Benin have shown support for Niger's resistance. This grassroots solidarity indicates a possibility of broader regional transformation beyond current military-led transitions.

The M62 movement in Niger, which holds daily protests supporting the military government, is an example of the popular mobilization behind military transitions. These movements are genuine grassroots organizations. This shows real popular support for sovereignty assertions. The consistency of anti-French demonstrations across multiple countries suggests a coordinated popular consciousness.

Civil society coalitions backing military governments have emerged across the Sahel. They provide civilian legitimacy for military leadership. For example, over 50,000 volunteers joined Burkina Faso's defence forces. This shows popular willingness to support sovereignty even at personal cost. These volunteer movements build alternative security structures independent of Western help. They also create popular ownership of independence struggles.

Pan-African solidarity demonstrations beyond the Sahel region indicate continental resonance for sovereignty movements. Social media has connected African youth across borders. This has created a shared consciousness about neocolonial exploitation and the possibilities for resistance. The emergence of continental rather than just national movements suggests a potential for coordinated African resistance to external domination.

Africa's youth, with a median age of 19, provide fertile ground for transformational politics. Young Africans have no memory of independence struggles. Yet they face daily realities of foreign domination in economic structures, military interventions, and political interference. This makes them receptive to radical alternatives that older generations might find threatening. Social media has enabled continental communication and organization. African youth can access alternative information sources and coordinate across borders. This technological democratization of information and organization provides infrastructure for continental movements that previous generations lacked. The revival of Pan-African consciousness among contemporary African youth draws inspiration from historical figures like Sankara. Young Africans increasingly reject inherited post-colonial arrangements as illegitimate. This generational shift creates conditions for systematic changes in continental governance.

Challenges and Obstacles Ahead

African sovereignty movements confront intense external pressure. Repeated assassination attempts against leaders like Captain Traoré demonstrate that some foreign interests see even political compromise as unacceptable, preferring covert violence to dialogue. Economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation, wielded despite their severe humanitarian impact, likewise aim to bend resistant governments to external will—but often only bolster domestic support rather than weaken it. Parallel to these hard-power tactics, Western-funded media and think-tank campaigns deploy disinformation and selective narratives—emphasizing instability, foreign influence, or governance failures—to delegitimize grassroots calls for self-determination and justify continued intervention.

At home, transitional administrations struggle to balance security with the urgent promise of civilian rule. Extending provisional timelines—or reverting to military oversight after failed attempts at democratic governance—risks eroding popular trust, especially given prior civilian leaders’ inability to tackle entrenched underdevelopment. Translating bold economic pledges into real improvements requires overcoming decades of weak institutions, chronic resource shortages, and corruption. Without rapid, effective delivery of jobs, infrastructure, and services, governments leave themselves vulnerable to both internal discontent and external exploitation of public frustration.

Meanwhile, the Sahel’s persistent jihadist insurgency and porous borders compound the challenge. French-led counter-terrorism efforts have yielded few lasting gains, highlighting the limits of relying on former colonial powers. Building indigenous security forces—whether trained domestically or supported by new partners like Russia and China—demands years of investment in training, intelligence, and logistics, even as extremist groups exploit local grievances to recruit and establish cross-border sanctuaries. Success will hinge on forging truly regional cooperation that resists outside meddling, enables rapid information-sharing, and prioritizes civilian protection alongside counter-terrorism.

The End of Françafrique: Implications for Global Order

France’s post-independence network of currency controls, military ties, and political patronage—collectively known as Françafrique—once secured Paris’s unfettered access to African resources, captive markets for its corporations, and strategic footholds across the continent. Designed for resilience, this neocolonial system adapted its tactics—ranging from coup-backed regime changes to economic carrots and sticks—whenever African leaders challenged French dominance. Yet today, mass popular awareness of the link between French influence and persistent underdevelopment, combined with the availability of new international partners, has rendered these tactical adjustments insufficient. As alternative alliances take hold, the very legitimacy of Françafrique has crumbled.

Parallel to France’s fallout, decades of neoliberal “structural adjustment” across sub-Saharan Africa have failed to deliver broad-based growth or reduce extreme poverty. Washington Consensus policies—conditional loans, privatizations, and deregulation—proved to serve external creditors more than local development needs. Having witnessed record levels of hardship under these regimes, African governments are now reclaiming economic sovereignty: nationalizing resources, mobilizing domestic revenues, and forging South–South partnerships that bypass IMF-World Bank conditionality. Early successes in revenue generation and infrastructure development under these alternative models are accelerating this shift.

These converging trends herald a profound geopolitical rebalancing. African states are diversifying their foreign relations, engaging China, Russia, India, and multilateral groupings like BRICS to counteract traditional Western leverage. Regional initiatives—such as the Alliance of Sahel States—and growing South–South financing networks challenge the Western-dominated Bretton Woods order by offering policy space without punitive conditionality. Moreover, the visible failure of sanctions and intervention to restore compliant governments in the Sahel emboldens other Global South movements resisting Western pressure. In sum, the demise of Françafrique not only reshapes Africa’s political economy but also undermines post-Cold War Western hegemony, contributing to a more multipolar international system.

Conclusion: Africa's Second Independence

Africa’s current transformation marks a definitive break from neocolonial legacies. Popular movements in the Sahel have dismantled colonial-era agreements, expelled foreign forces, and forged new alliances that deliver real economic gains—particularly through resource nationalism and regional cooperation. Institutional advances like the Alliance of Sahel States, with shared defence structures and alternative monetary systems, signal a durable shift rather than a fleeting protest.

This awakening offers a blueprint for other post-colonial regions. By reclaiming currency sovereignty, controlling natural resources, and mobilizing domestic revenues, African governments have demonstrated that sustained independence is both feasible and beneficial. Youth-driven leadership further underscores the need for generational renewal where entrenched elites cannot overcome inherited constraints.

True Africa–Europe partnership now depends on mutual respect and equality. Europe must recognize African sovereignty over resources, monetary policy, and political choices or face continued resistance. Meaningful dialogue on reparations, historical accountability, and debt restructuring will be essential to establish durable, equitable ties rather than attempting to preserve outdated hierarchies.

Epilogue: The Global South Rises

Africa’s bold assertion of sovereignty has transcended continental borders to reshape global governance. By demanding permanent UN Security Council seats and pioneering South–South cooperation networks, African states model alternative international institutions free from Western monopoly. Their leadership in BRICS, the Alliance of Sahel States, and other multilateral platforms demonstrates that truly equitable representation and policy autonomy are achievable.

The successful resistance to Western economic and military coercion in Africa inspires similar movements across the Global South. Having weathered sanctions, expelled foreign forces, and secured new strategic partnerships, African countries offer a powerful example to Asia, Latin America, and beyond. This “demonstration effect” accelerates multipolar shifts, weakening traditional Western leverage over development and security policy worldwide.

On the economic front, Africa has dispelled myths of Western indispensability by deploying homegrown development strategies. Resource nationalism, regional value chain integration, and domestic revenue mobilization through mechanisms like BRICS’s New Development Bank provide concrete alternatives to IMF and World Bank oriented conditionality. The pivot from raw export dependency to local processing and value addition further undermines colonial economic hierarchies and builds durable fiscal independence.

Finally, 21st century decolonization must encompass cultural and spiritual liberation alongside political and economic emancipation. From downgrading colonial languages to reclaiming public spaces in memory of independence heroes, African societies are rewriting their own narratives. Pan African unity, epitomized by regional defence and economic frameworks, cements a collective identity capable of resisting external domination and charting an autonomous future for the entire Global South.

. . .

References:

- https://panor.ru/articles/rossiya-v-borbe-za-niger/108927.html

- https://africajournal.ru/en/2024/07/01/political-turmoil

- https://democracyinafrica.org/changing-alliances-a-critical

- https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/02/russias

- https://research-portal.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/

- https://reliefweb.int/report/niger/ecowas-nigeria

- https://online.ucpress.edu/currenthistory

- https://www.voanews.com/a/coup-threatens-niger

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/11/22/niger

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/niger/overview

- https://ijsmpcr.com/index.php/ijsmpcr/article/view/36

- https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Niger/foreign_aid/

- https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french

- https://reliefweb.int/report/burkina-faso

- https://www.grpublishing.org/journals/index

- http://bullionworld.in/more-mining-refining.php

- https://www.ecofinagency.com/mining/1810-46039

- https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2021/04/16/649577

- https://afripoli.org/the-magnetic-pull-of-brics

- https://www.cadtm.org/The-Sankara-Affair-Press-release

- https://www.thomassankara.net/affaire-sankara

- https://scienceopen.com/hosted-document?

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37643926

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-61008332

- https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/mausoleum

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080

- https://journals.rcsi.science/0321-5075/article/view/265317

- https://rsisinternational.org/journals/ijriss/articles

- https://www.africanews.com/2023/12/07

- https://www.lalive.law/the-impact-of-malis-revised

- https://credendo.com/en/knowledge-hub

- https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.35.2914

- https://www.cadtm.org/The-Thomas-Sankara-affair

- https://fts.unocha.org/countries/162/summary/2022

- https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/56355.html

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release

- https://fts.unocha.org/countries/162/donors

- https://www.democracynow.org/2017/11/30/headlines

- https://www.ecofinagency.com/public-management

- https://mine.nridigital.com/mine_jul24

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-42151353

- https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/f1136e8

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://jacobin.com/2022/04/thomas-sankara-blaise

- https://reliefweb.int/report/niger/regional

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper

- https://www.worldometers.info/world-population

- https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20171129-france

- https://www.heraldonline.co.zw/reviving-thomas