Photo by Dave Contreras on Unsplash

I. Prologue: The Global Resonance of Yoga Day

The modern world annually turns its gaze towards an ancient practice on June 21st, celebrating International Yoga Day (IDY). This global observance marks a profound recognition of yoga's multifaceted benefits, spanning physical vitality, mental tranquillity, and spiritual growth. The celebration, spearheaded by India, transcends mere physical exercise, serving as a powerful testament to a timeless tradition that has now captivated the global imagination.

The theme for International Yoga Day 2025, "Yoga for One Earth, One Health," encapsulates a broader vision, emphasizing the intrinsic connection between human well-being and environmental sustainability. This aligns seamlessly with the G20's overarching principle of "One Earth, One Family, One Future," extending yoga's appeal beyond individual health to encompass a collective responsibility towards the planet and its inhabitants. India's commitment to integrating yoga into everyday life is evident in the elaborate arrangements for the day, including key events such as Yogamahotsav, Yoga Sangama, Yoga Bandhan, and Yoga Maha Kumbh, organized by the Ministry of AYUSH. These initiatives underscore a national dedication to mainstreaming this ancient practice.

The genesis of International Yoga Day can be traced to a landmark proposal by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the United Nations General Assembly in 2014. This initiative garnered unprecedented international support, with a record 177 countries co-sponsoring the UN resolution, which subsequently passed unanimously. The inaugural IDY was celebrated globally on June 21, 2015, with widespread participation in major cities worldwide, including New York, Paris, Beijing, and New Delhi. The chosen date, coinciding with the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, holds special significance in many cultures, further enhancing its universal appeal. The first celebration in New Delhi notably involved 35,985 participants from 84 nations performing 21 yoga postures, setting a world record for the largest yoga class.

The global celebration of yoga, particularly through IDY, functions as a powerful instrument of India's cultural diplomacy, significantly enhancing its soft power on the international stage. It positions yoga not merely as a wellness practice but as a "timeless gift" and a "philosophical offering" from India to the world, transcending geographical, religious, and ideological boundaries. The Prime Minister's deep personal commitment to yoga is integral to this global projection, transforming an ancient discipline into a strategic tool for cultural outreach. The embedded principles of yoga, such as ahimsa (non-violence), santosha (contentment), and aparigraha (non-possessiveness), carry profound implications for contemporary global discourse on peacebuilding, climate change, and mental health. This allows yoga to serve as a powerful tool for fostering collective healing and coexistence in an increasingly fragmented world.

The widespread and rapid global adoption of International Yoga Day, as evidenced by the overwhelming co-sponsorship at the UN and its immediate worldwide celebration, indicates a highly effective strategic deployment of India's ancient cultural heritage as a form of soft power. This phenomenon suggests a significant development in global diplomacy, where cultural contributions can exert influence comparable to economic or military strength, enabling India to project its civilizational values on a global scale. There is a nuanced dynamic at play in this global promotion. While the Prime Minister has articulated that yoga is "not a religious practice," emphasizing its universal appeal, India's minister of yoga has simultaneously expressed the intent to establish yoga as "India's cultural property". This dual objective highlights a delicate balance: the desire to universalize yoga for broader acceptance while simultaneously asserting its distinct Indian origin and heritage. The global popularity of IDY suggests that the narrative of "universal wellness" has largely resonated, yet the underlying aim of cultural ownership remains a significant, albeit subtle, aspect of India's strategic cultural diplomacy.

II. Echoes from Antiquity: The Genesis and Evolution of Yoga in India

The journey of yoga is a profound historical narrative, tracing its origins from the earliest human settlements in India through millennia of philosophical development and practical refinement. It is a story deeply interwoven with the subcontinent's spiritual and cultural fabric.

A. Pre-Vedic Whispers: The Earliest Glimpses

The practice of yoga is often believed to have emerged at the very dawn of civilization, predating formal religious systems by thousands of years. Archaeological discoveries from the Indus Saraswati Valley Civilization, dating back to approximately 2700 BCE, offer compelling, albeit speculative, evidence of early yogic culture. Seals and fossil remain unearthed from these ancient sites depict figures in postures reminiscent of yogic practices, with the iconic idol of Pashupati often cited as an example of a figure in a yogic stance.

However, it is important to approach these early interpretations with academic caution. While these archaeological findings are intriguing, contemporary scholarship views the direct identification of these figures with established yoga practices as speculative. The true meaning of the Pashupati seal, for instance, remains elusive until the Harappan script is deciphered, preventing a definitive link between the roots of yoga and the Indus Valley Civilization. This underscores the critical need for nuanced interpretation in historical research, acknowledging the limitations of current evidence rather than presenting speculative claims as conclusive facts. The assertion that yoga began at the "dawn of civilization," while evocative, is therefore based on interpretative readings of ancient artifacts rather than undisputed historical records.

B. Vedic Hymns and Upanishadic Insights: The Philosophical Bedrock

The more concrete historical origins of yoga are found within the ancient scriptures of India, including the Vedas, the Upanishads, and later, the Bhagavad Gita. The Rigveda, considered one of the oldest sacred texts, composed between approximately 1200 and 900 BCE, contains hymns that allude to practices of yoga and meditation as a pathway to spiritual enlightenment. The Nasadiya Sukta within the Rigveda, for example, hints at an early contemplative tradition within Brahmanism. Further Vedic texts, such as the Atharvaveda and the Brahmanas (dating from around 1000–800 BCE), contain references to techniques involving the control of breath and vital energies, indicating nascent forms of what would later become formalized yogic practices.

The Upanishads, emerging in the first half of the first millennium BCE, marked a significant philosophical deepening of these early practices. These profound texts delve into the metaphysical dimensions of yoga, emphasizing the concept of Atman (the individual soul) uniting with Brahman (the universal consciousness) through self-realization. The Upanishads thus provided the foundational philosophical framework for yoga's spiritual journey, shifting the focus from externalized ritualistic practices, which were more prominent in earlier Vedic traditions, to an internalized, self-realization-oriented discipline. This progression from early contemplative hints to explicit philosophical inquiry represents a crucial evolution in the understanding and purpose of yoga, laying the deep intellectual groundwork for all subsequent yogic traditions and transforming it into a path of profound self-discovery.

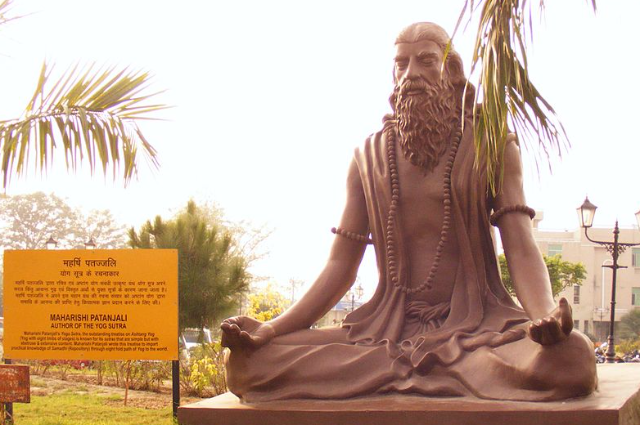

C. The Classical Codification: Patanjali's Yoga Sutras

A pivotal moment in the history of yoga arrived with the systematic compilation of the Yoga Sutras by the sage Patanjali, estimated to be around 400 CE. This seminal text is widely regarded as the foundational treatise of classical yoga philosophy. Patanjali meticulously delineated the eight limbs, or Ashtanga, of yoga, providing a comprehensive framework for spiritual discipline. These limbs include: ethical principles (yamas and niyamas), physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and spiritual absorption (samadhi).

Patanjali's work was not merely a documentation of existing practices but a transformative act of codification. By systematically organizing these diverse elements into a coherent eight-limbed path, he provided a universal and structured framework for yogic practice and philosophy. This standardization was instrumental in the consistent transmission and interpretation of yoga across various lineages and geographical regions, ensuring its enduring survival and adaptability over millennia. Without this coherent philosophical basis, yoga might have remained a collection of disparate techniques rather than evolving into the globally recognized and influential system it is today.

D. Diverse Paths and Epic Narratives: Yoga in Indian Traditions

Yoga's evolution in India saw the emergence of diverse paths and its integration into major philosophical and religious narratives, showcasing its adaptability and widespread influence.

Yoga in the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita, a revered scripture embedded within the epic Mahabharata, presents a profound philosophical dialogue between the warrior Arjuna and Lord Krishna, his charioteer and divine guide. This conversation serves as a powerful metaphor for the internal struggles individuals encounter throughout their life journeys. At its core, the Bhagavad Gita emphasizes understanding the true nature of the self as a central tenet of yoga philosophy, illustrating the concept of the body as a temporary vessel for the eternal soul.

The text introduces several key yogic paths. Karma Yoga, the path of selfless action, is central, advising practitioners to perform their duties without attachment to the outcomes. This principle encourages focusing on the act itself rather than the desired result.

Bhakti Yoga, the path of devotion, is also presented, advocating for a shift in perspective from self-centered desires to selfless contribution and devotion to a higher good or truth. Furthermore, Jnana Yoga, the path of wisdom and knowledge, is explored, with Krishna imparting deep spiritual knowledge to Arjuna, akin to a teacher guiding students to a deeper understanding of themselves and the universe.

Connections with Samkhya Philosophy

The philosophical underpinnings of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras are rooted in Samkhya philosophy. Within the Bhagavad Gita, Samkhya Yoga refers to a path of knowledge and self-realization, focusing on discerning the true nature of reality. A key aspect of this approach is the emphasis on distinguishing between the eternal soul (Atman) and the temporary physical body, fostering a profound understanding of one's true essence. This philosophical stance encourages detachment from the material world and performing one's duties without being swayed by the outcomes, promoting a balanced and disciplined mindset in the face of life's challenges.

Emergence of Hatha Yoga and Tantric Traditions

The post-classical period witnessed the significant emergence of Hatha Yoga, a foundational practice for many contemporary yoga styles. Hatha Yoga concentrates on harmonizing the body and mind through a combination of physical postures (asanas), controlled breathing techniques (pranayama), and cleansing practices (shatkarma). While texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (12th-17th centuries CE) provide detailed insights into its practices, earlier mentions of similar physical and meditative techniques can be found in the Bhagavad Gita and Patanjali's Yoga Sutras. Some Hatha yoga techniques are even traceable to the 1st century CE in Hindu Sanskrit epics and the Buddhist Pali canon.

Notably, the 11th-century Amṛtasiddhi, a tantric Buddhist work, is recognized as the earliest substantial text describing Hatha yoga, even if it does not explicitly use the term. Parallel to Hatha Yoga, Tantra emerged in ancient India, evolving as a response to the changing spiritual landscape of the time. Tantra encompasses esoteric doctrines and practices, with proto-tantric elements even suggested in the Rig Veda. It is often associated with the concept of raising Kundalini, a spiritual energy believed to reside at the base of the spine.

The diversification of yoga into distinct paths such as Karma, Bhakti, and Jnana Yoga within the Bhagavad Gita, followed by the development of Hatha Yoga and Tantra, illustrates yoga's profound adaptability. This diversification allowed yoga to cater to a wide spectrum of human temperaments and spiritual inclinations—whether through action, devotion, knowledge, or physical discipline—preventing it from becoming a rigid, singular system.

This inherent inclusivity was crucial for its widespread adoption and enduring relevance across various segments of Indian society, ensuring that the path to self-realization remained accessible through multiple avenues.

Yoga's Role in Buddhism and Jainism: Shared Principles and Distinct Goals

Yoga practices hold significant emphasis in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions as a means of achieving liberation from the cycle of rebirth. The earliest forms of yoga practices may have even appeared within the Jain tradition around 900 BCE. Furthermore, expositions on yoga-like concepts and practices are found in Jain and Buddhist texts dating from approximately 500 to 200 BCE. It is believed that Gautama Buddha himself studied with a Samkhya teacher, and some scholarly perspectives suggest that certain forms of Buddhism, particularly Theravada, may have philosophical roots in Samkhya and earlier components of the Yoga Sutras.

While various yogic practices are considered beneficial across Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, their ultimate philosophical goals diverge. Hindu yoga, particularly as articulated in the Yoga Sutras, often aims for the realization of Atman (the purified, eternal self) and its union with Brahman. In contrast, Buddhism strives for An-atman (the concept of no-self or non-self), emphasizing the impermanence and interconnectedness of all phenomena. It is also noteworthy that the specific term "yoga" as a developed spiritual practice is largely absent from canonical Buddhist and Jain texts, with its earliest explicit references found in the Vedic Upanishads and the Mahabharata. This suggests that while there was significant influence and shared contemplative practices, these traditions maintained distinct philosophical identities and ultimate spiritual objectives.

The presence of yogic practices across Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism points to a dynamic intellectual and spiritual environment in ancient India, characterized by significant cross-pollination of ideas and methodologies. While these traditions shared common elements like breath control and meditation, and Buddhism was influenced by Samkhya philosophy, their fundamental philosophical aims remained distinct. This highlights that while practical methodologies could be adapted or borrowed, the core metaphysical tenets of each religion ultimately dictated the purpose and interpretation of these practices. It underscores a vibrant historical context where ideas flowed freely, yet each tradition preserved its unique identity and spiritual endpoint.

Table 1: Key Eras in Yoga's Historical Development in India

| Era | Timeline (Approximate) | Key Characteristics/ Developments | Key Texts/Figures |

| Pre-Vedic | c. 3000-1500 BCE | Archaeological evidence of figures in yogic postures (Indus Valley Civilization) | Indus Valley seals, Pashupati idol |

| Vedic | c. 1500-500 BCE | Earliest mentions of contemplative practices and meditation | Rigveda, Atharvaveda, Brahmanas |

| Upanishadic | c. 800-400 BCE | BCE Deep philosophical foundations; emphasis on Atman-Brahman union | Upanishads |

| Classical | c. 400 CE - 800 CE | Systematic codification of yoga as a spiritual discipline | Patanjali's Yoga Sutras (Ashtanga) |

| Post-Classical | c. 800 CE - 1700 CE | Diversification of yogic paths; emergence of Hatha and Tantra | Bhagavad Gita, Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Matsyendranatha, Gorakhnath |

| Modern | c. 1700 CE - Present | Revival and globalization of yoga; modern schools and international recognition | Swami Vivekananda, B.K.S. Iyengar, K. Pattabhi Jois, Swami Sivananda, Swami Satyananda Saraswati |

III. Yoga's Cultural Imprint: A Living Tradition

Yoga is not merely a set of ancient practices; it is a living tradition that has profoundly shaped the cultural, social, and health landscape of India. Its principles permeate various aspects of daily life, influencing well-being, art, and literature, and maintaining a symbiotic relationship with other indigenous sciences like Ayurveda.

A. Weaving into Daily Life and Holistic Health

Yoga is deeply woven into the cultural and spiritual heritage of India, influencing the physical, mental, and spiritual well-being of individuals for thousands of years. Within the Indian context, yoga is perceived as far more than a physical exercise; it is a holistic approach to health and well-being, striving for harmony between the body and mind, thought and action, and humanity and nature. It is regarded as a comprehensive "way to lead a holistic life and to attain enlightenment," encompassing fundamental principles such as proper relaxation, exercise, breathing, diet, positive thinking, and meditation.

Yoga is recognized as a powerful tool for balancing the body's three fundamental energies, known as doshas, and offers substantial benefits in preventing and managing prevalent lifestyle disorders, including diabetes and hypertension. Its practices are also effective in mitigating psychological stress and enhancing the body's innate immune response. The understanding that yoga is a comprehensive lifestyle system, rather than just a series of physical postures, is foundational to its cultural imprint in India. This perspective views yoga as providing a complete framework for physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, extending beyond a mere fitness regimen. This deeper, culturally embedded understanding challenges the often-reductive interpretations prevalent in some modern contexts, where the emphasis might solely be on its physical aspects.

B. Artistic and Literary Reflections

Throughout Indian history, the influence of yoga has been vividly captured in its art and literature, serving as a visual and textual chronicle of its integration into religious and cultural practices. Temples and sculptures from various periods are adorned with figures depicting yogic poses, illustrating the deep embedding of yoga within the spiritual landscape.

While ancient Indian statuary features ascetics in meditative postures, more detailed and naturalistic depictions of Indian ascetics in paintings began to emerge around 1560 CE, particularly under the patronage of the Mughal Emperors Akbar and his successors. These Mughal paintings are not merely artistic expressions; they function as invaluable historical documents, offering rich insights into the lives of yogis, their appearances, sectarian affiliations, and even instances of conflict. They complement and, at times, even correct the historical narratives gleaned from Sanskrit and vernacular texts, traveller’s reports, and hagiographies. For example, these visual records help identify distinct yogi sects, such as the Nāths and Saṃnyāsīs, through their specific attributes and attire.

The portrayal of battles between rival yogi suborders over alms collection at festivals further illuminates the societal interactions and challenges faced by these ascetic groups. This demonstrates that art provides a unique historical commentary and a mirror reflecting societal dynamics, enriching the understanding of yoga's cultural imprint beyond textual accounts.

Beyond visual arts, yoga's philosophical discussions and practices are deeply woven into the fabric of Indian literature, notably in epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and are also present in various folk traditions.

C. Sister Sciences: The Symbiotic Relationship with Ayurveda

Yoga and Ayurveda are often referred to as "sister sciences," having originated in India thousands of years ago and sharing a common philosophical and linguistic heritage. Ayurveda, the traditional system of medicine in India, intrinsically incorporates yogic principles related to diet, lifestyle, and herbal remedies to promote holistic healing.

At the heart of Ayurveda lies a personalized health philosophy based on unique individual constitutions, or doshas—Vata, Pitta, and Kapha—which are linked to the fundamental elements. Understanding one's specific dosha allows for the customization of yoga practices, including asanas (postures), pranayamas (breath control), and dietary choices, to achieve optimal health and vitality. This integrated approach highlights a sophisticated, holistic health paradigm where physical, mental, and spiritual well-being are viewed as inseparable and mutually reinforcing.

Historically, while yoga gained global prominence, particularly in the West, it often diverged from its Ayurvedic roots. This separation, partly influenced by historical factors such as the closure of Ayurvedic schools during the colonial era, led to a more physically oriented interpretation of yoga. However, there is a growing global movement to reconnect these two complementary practices, recognizing their profound synergistic potential for enhancing the health of the body, mind, and higher awareness. Ayurveda provides a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment framework, which yoga practices complement directly.

For instance, asana is considered the "external medicine of Yoga," working on the musculoskeletal system, while pranayama is viewed as the "internal medicine," primarily impacting the circulatory, nervous, respiratory, and digestive systems, thereby increasing energy and vitality. The modern re-integration of yoga and Ayurveda represents a vital step towards restoring yoga's full potential as a comprehensive healing system, moving beyond a simplified, purely physical practice to embrace its ancient, integrated depth.

IV. Universal Quest: Meditative and Mind-Body Practices Across Civilizations

While yoga's origins are distinctly Indian, the human endeavour to achieve mind-body harmony and spiritual insight is a universal phenomenon, manifesting in various forms across diverse ancient civilizations. A comparative examination reveals shared aspirations, even amidst divergent expressions and methodologies.

A. Ancient Egypt: Contemplative Poses and Spiritual Disciplines

In ancient Egypt, meditation was a foundational element of well-being, deeply woven into daily life and spiritual journeys. The Egyptian worldview was profoundly rooted in the sacred, emphasizing harmony and balance not only in the physical realm but also within the individual soul. Meditation served as a pathway to inner peace, deeper understanding, and a profound connection with the cosmos.

Evidence suggests that the very architecture of their temples and the intricate rituals performed within them, including rhythmic chanting and carefully orchestrated movements, were designed to facilitate meditative states, guiding practitioners towards a divine connection. Hieroglyphs and surviving artifacts depict individuals in contemplative poses, often accompanied by religious symbols and offerings, indicating practices that involved focused mental states, visualizations, and possibly mantras linked to specific deities. The ancient Egyptians recognized a strong link between mental clarity and physical health, understanding that a disturbed mind could lead to illness.

Consequently, meditation was a crucial tool for maintaining emotional equilibrium and overall well-being, not solely for spiritual enlightenment. Some ancient Egyptian practices, referred to as "Egyptian Yoga" or "Egyptian Postures of Power," utilized sacred movements, postures, and body geometry for energy healing and spiritual growth, showing functional similarities to practices like Qigong, Tai Chi, and Vedic Mudras. The presence of such contemplative and mind-body practices in ancient Egypt suggests a parallel, independent evolution of holistic spiritual and health disciplines outside of India. This indicates a universal human inclination to explore and cultivate internal states through disciplined practices, demonstrating that the pursuit of integrated well-being is a recurring theme across diverse ancient cultures, even if the specific forms and philosophical underpinnings differ from Indian yoga.

B. Classical Greece: Philosophy, Physical Training, and the Mind-Body Ideal

The ancient Greeks held a holistic view of well-being, emphasizing the intricate interconnectedness of the body, mind, and spirit. A famous adage, "A healthy mind in a healthy body" (Nous Hygiēs en Sōmati Hygiei), perfectly encapsulates their belief that physical fitness was indispensable for mental acuity and overall health. Philosophers such as Pythagoras and Socrates advocated for exercise not merely for physical health but also for "nourishing happiness of mind" and cultivating wisdom, highlighting its broader transformative potential.

Physical training in ancient Greece, often rigorous as seen in the preparation of Olympians, was considered a practice that shaped the entire self, fostering virtues like arete (excellence) and sophrosyne (discipline). Plato's philosophical insight that "The soul becomes dyed with the colour of its thoughts" further underscores their deep understanding of the mind-body connection, implying that mindful effort during physical activity could expand consciousness. The ancient Greek emphasis on a "healthy mind in a healthy body" and the philosophical integration of physical training with mental and spiritual development reveals a striking convergence with yoga's holistic aims.

However, while yoga primarily sought spiritual liberation and self-realization, Greek practices, though holistic, often had a more civic, athletic, or military focus, aimed at preparing citizens for defence and public life. This highlights that while different civilizations independently arrived at the understanding of the mind-body connection as crucial for human flourishing, the ultimate societal and individual goals driving these practices could vary significantly, leading to distinct manifestations of similar underlying principles.

C. Ancient China: Qigong and Tai Chi

Ancient China developed its own sophisticated systems of mind-body cultivation, notably Qigong (pronounced "chi-gong") and Tai Chi Chuan. Qigong is an ancient Chinese practice that integrates movement, breathing, and mental concentration, with its roots tracing back to Daoist traditions around 2146 BCE. This practice operates on the principle of circulating qi (vital energy or life force) through the body's meridians, thereby influencing the health and function of internal organs, a core concept in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

Tai Chi Chuan, a closely related discipline, originated as a martial art before gaining popularity as a health-promoting exercise. It employs flowing, rhythmic, and deliberate movements that blend physical exercise with meditation, embodying the Daoist principle of harmonizing yin and yang. Early forms of Qigong, known as Dao Yin, involved breathwork and meditative movements for healing and spiritual connection, influenced by ancient Chinese shamans. Over time, Qigong was influenced by Buddhist practices, particularly Chan (Zen) meditation, which incorporated breath control and mindfulness, and was also integrated into martial arts to enhance strength and internal energy. The development of Qigong and Tai Chi in ancient China, with their focus on cultivating Qi through breath, movement, and meditation, represents another distinct yet functionally analogous tradition to yoga. This parallel evolution, rooted in Daoist philosophy and Traditional Chinese Medicine, underscores a universal human understanding that the management of internal energy is fundamental to health, longevity, and spiritual insight. The integration of these practices with healing and martial arts further highlights their practical and adaptable nature, demonstrating how ancient cultures independently discovered and refined methods for optimizing the mind-body connection through the lens of energy cultivation.

D. A Comparative Lens: Shared Aspirations, Diverse Expressions

A comparative examination of these ancient traditions reveals that while yoga is distinctly Indian, the fundamental human quest for mind-body harmony and spiritual insight is a universal aspiration, expressed through diverse cultural forms.

Common themes resonate across these distinct practices:

- Self-awareness and inner peace: A central pursuit in Egyptian meditation, a goal of Greek philosophical exercise, and a benefit of Chinese Qigong.

- Balance and harmony: Emphasized in the Egyptian concept of Ma'at, the Greek ideal of a healthy mind in a healthy body, and the Yin-Yang principles in Chinese Tai Chi.

- Spiritual connection or transcendence: A core objective in Indian yoga's pursuit of Atman-Brahman union, a key outcome of Egyptian meditative practices and connection with deities, and a goal of Daoist internal alchemy in Qigong.

- Discipline and consistent practice: Fundamental to Patanjali's Ashtanga Yoga, stressed in Greek physical training for excellence, and inherent in Chinese Dao Yin practices.

Despite these shared aspirations, each civilization developed unique methodologies. India's yoga, particularly through asanas and pranayama, primarily aims for spiritual liberation and self-realization. Egypt's meditative practices were often ritualistic and closely linked to specific deities. Greece's gymnastike fostered civic virtue and athletic prowess. China's Qigong and Tai Chi focused on Qi cultivation for health and longevity, often integrated with martial arts.

The comparative analysis reveals that despite geographical and cultural separation, ancient civilizations like India, Egypt, Greece, and China developed sophisticated mind-body practices that share fundamental aspirations: achieving inner harmony, enhancing self-awareness, promoting health, and connecting with a higher principle. This indicates an archetypal human quest for wholeness and transcendence, manifested through diverse cultural expressions. The differences in methodology highlight how universal human needs are addressed through culturally specific frameworks, enriching the global tapestry of human wisdom.

Table 2: Comparative Overview of Ancient Mind-Body Practices

| Civilization/ Tradition | Origins/ Timeline (Approximate) | Key Elements/ Practices | Primary Objectives |

| Ancient India (Yoga) | Indus Valley/Vedas (c. 2700 BCE+) | Asanas, Pranayama, Meditation, Ethical principles | Self-realization, Liberation, Union with Brahman |

| Ancient Egypt (Meditative Practices/ "Egyptian Yoga") | Shamans/Early Dynastic (c. 3000 BCE+) | Contemplative poses, Chanting, Rituals, Breathwork | Inner peace, Divine connection, Harmony with Ma'at |

| Classical Greece (Physical/ Philosophical Training) | Philosophers (c. 600 BCE+) | Gymnastics, Philosophical discourse, Mind-body sayings | Holistic well-being, Civic virtue, Excellence |

| Ancient China (Qigong/Tai Chi) | Shamans/ Daoism (c. 2146 BCE+) | Movement, Breathwork, Qi cultivation, Meditation | Health, Longevity, Energy balance |

V. Epilogue: Yoga's Enduring Legacy and Future Horizon

The journey of yoga, from its ancient and sometimes speculative origins to its modern global prominence, is a testament to its profound and enduring relevance. Beginning with the subtle hints in the Indus Valley Civilization and the philosophical bedrock laid by the Vedas and Upanishads, yoga steadily evolved through the classical systematization by Patanjali. This evolution led to the diversification into various paths—Karma, Bhakti, Jnana, Hatha, and Tantra—each offering a distinct yet interconnected route to self-realization.

Yoga's deep cultural imprint on Indian society is undeniable, influencing not only health practices and daily life but also finding expression in art and literature, and maintaining a vital, symbiotic relationship with Ayurveda. Furthermore, the human quest for mind-body harmony is not confined to India; parallel practices in ancient Egypt, Greece, and China demonstrate a universal aspiration for inner balance and transcendence, albeit expressed through diverse cultural methodologies. The modern manifestation of International Yoga Day stands as a powerful symbol of yoga's global reach and India's successful cultural diplomacy.

Yoga continues to inspire individuals worldwide in their pursuit of truth and inner peace. Its timeless principles offer practical solutions to many contemporary global challenges, including escalating stress levels, the rise of lifestyle disorders, and growing mental health concerns. The holistic approach inherent in yoga, which seamlessly integrates the body, mind, and spirit, remains crucial for promoting overall well-being and fostering sustainable living practices. The journey of yoga, from its ancient philosophical roots to its modern global recognition through International Yoga Day, highlights its remarkable adaptability and enduring relevance. In a world increasingly grappling with stress, lifestyle disorders, and mental health crises, yoga offers a time-tested, holistic framework for well-being that transcends cultural boundaries. This underscores that ancient wisdom traditions, far from being mere historical artifacts, can provide profound and practical solutions to pressing contemporary global challenges, positioning yoga not just as a historical phenomenon but as a living, evolving science for human flourishing and planetary harmony.