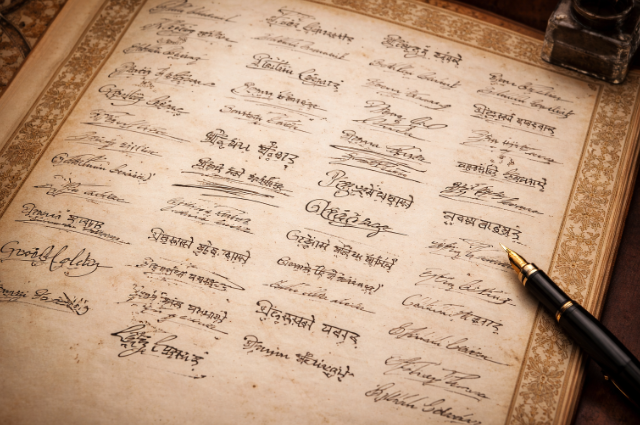

When the Constitution of India was adopted on 26 January 1950, it did more than establish a legal framework for the world’s largest democracy. It captured, in ink and script, the profound cultural diversity of a newly independent nation. One of the most overlooked yet deeply symbolic features of the Constitution is the page of signatures at its end. Written not in a single uniform script but in many, these signatures represent a visual and cultural tapestry of India’s multilingual identity. They stand as silent testimony to unity forged not through sameness, but through respectful coexistence.

At a time when the scars of Partition were still fresh and the challenges of nation-building were immense, the framers of the Constitution made a deliberate choice: to allow members of the Constituent Assembly to sign the document in their own languages and scripts. This decision transformed the Constitution into more than a legal text—it became a cultural artefact reflecting India’s civilizational depth.

India’s Linguistic Landscape at Independence

India’s linguistic diversity predates modern political boundaries by centuries. Sanskrit, Prakrit, Pali, Persian, Arabic, Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, Gujarati, and many other languages have shaped the intellectual and cultural history of the subcontinent. By the mid-twentieth century, this diversity posed a serious political challenge. Language had already proven capable of dividing populations, and debates over a national language were among the most contentious in the Constituent Assembly.

Hindi and English eventually emerged as official languages for governance, but the framers were careful not to equate administrative convenience with cultural supremacy. The multilingual signatures reflect this caution. They silently affirm that while the Constitution would operate through specific languages, it belonged equally to speakers of all Indian tongues.

The Constituent Assembly and Its Cultural Sensitivity

The Constituent Assembly consisted of representatives from different regions, religions, castes, and linguistic backgrounds. Figures such as Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Rajendra Prasad, Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, and others were acutely aware that symbols matter in nation-building. Allowing members to sign in their native scripts was a symbolic act of inclusion.

These signatures appear in scripts such as Devanagari, Bengali, Gurmukhi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Gujarati, Urdu (Perso-Arabic), and even English cursive. Each script carries centuries of literary, religious, and philosophical heritage. Together, they visually narrate India’s pluralism far more effectively than any constitutional article could.

Signatures as Acts of Cultural Assertion

A signature is not merely a name; it is a declaration of identity. By signing in their own scripts, members asserted that regional identities need not dissolve into the national identity. Instead, the nation would be strengthened by acknowledging and preserving them.

For example, the presence of Urdu signatures affirmed the place of Muslim cultural heritage in a secular India, especially significant in the aftermath of Partition. Similarly, signatures in Dravidian scripts such as Tamil and Telugu underscored the equal status of South Indian cultures within a nation often perceived as North-centric.

This act subtly rejected the colonial legacy of linguistic hierarchy, where English had been privileged above indigenous languages. Though English remained an associate official language, the Constitution’s signatures restored dignity to Indian scripts long marginalised under colonial administration.

Calligraphy and Aesthetic Unity

The original Constitution was handwritten and illustrated by calligraphers and artists, most notably Prem Behari Narain Raizada. The handwritten text itself was a statement against mechanical uniformity. The multilingual signatures complemented this aesthetic vision. Despite the diversity of scripts, the final pages maintain a visual harmony, symbolising unity without erasure.

This artistic choice reinforces the idea that India’s democracy was not merely borrowed from Western models but rooted in indigenous traditions of pluralism, debate, and accommodation.

Legal Equality Beyond Language

Importantly, the multilingual signatures do not imply legal fragmentation. The Constitution remains a single, unified legal document. Instead, they communicate that equality before the law does not require cultural uniformity. This distinction is crucial in understanding India’s constitutional philosophy.

Unlike some nation-states that attempted to impose linguistic homogeneity, India chose accommodation. The Eighth Schedule of the Constitution, which recognises multiple languages, echoes the same spirit reflected visually in the signatures.

Contemporary Relevance

Even today, language remains a sensitive political issue in India. Debates over language imposition, education policies, and regional autonomy continue to surface. In this context, the multilingual signatures serve as a reminder of the original constitutional promise: that India would remain a union of cultures, not a monoculture imposed from the centre.

For students, scholars, and citizens alike, revisiting these signatures encourages a deeper appreciation of constitutional values beyond legal clauses. They invite us to reflect on the kind of unity India envisioned at its birth—one that respected difference rather than feared it.

The multilingual signatures of the Indian Constitution are far more than ceremonial marks at the end of a historic document. They are visual affirmations of India’s plural soul. In allowing each member to sign in their own script, the framers acknowledged that democracy in India could only survive through mutual respect and cultural recognition.

Seventy-five years later, these signatures continue to speak. They remind us that the strength of the Indian Constitution lies not just in its articles and amendments, but in its deep understanding of the land and people it represents—a true tapestry of scripts, voices, and identities bound together by a shared commitment to justice and unity.

References

- Austin, Granville. The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation. Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Basu, D. D. Introduction to the Constitution of India. LexisNexis, 2018.

- Constituent Assembly Debates, Government of India (1946–1949).

- Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi. HarperCollins, 2007.

- Government of India. The Constitution of India (Original Manuscript), Parliament Library, New Delhi.

- Thirumalai, M. S. Language Policy in Education in India. Language in India Foundation, 2002.