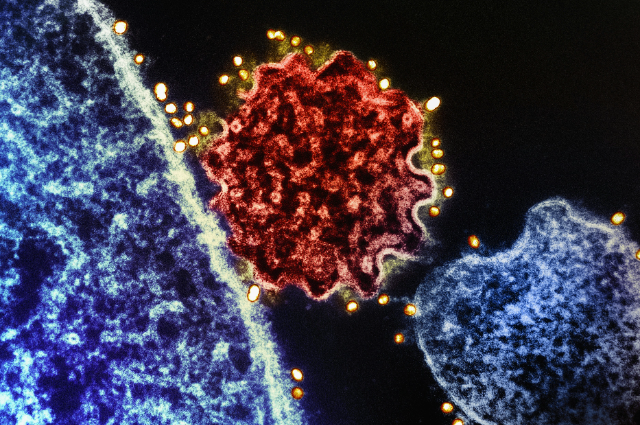

Photo by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases on Unsplash

A quiet alarm has been resounding across Asia. Two healthcare workers in India's West Bengal state fell ill in late December, and tests confirmed what health officials had feared that the Nipah virus had returned. Though only two cases have been confirmed, the response has been swift and serious. Countries across the region are now screening travellers at airports, and there is anxiousness about a disease most had never heard of before.

This isn't the first time Nipah has appeared, and that's precisely what makes it frightening. The virus has a dark reputation, and for good reason.

What Makes Nipah So Dangerous?

Nipah virus is what scientists call a zoonotic disease, meaning it jumps from animals to humans. The primary carriers are fruit bats and flying foxes, creatures that silently harbour the virus without getting sick themselves. Humans can catch it by eating fruit or drinking palm sap contaminated with bat saliva or urine, or through direct contact with infected animals. But perhaps most concerning is that the virus can spread from person to person, which is likely how the two healthcare workers in West Bengal became infected.

Once inside the human body, Nipah doesn't waste time. The virus typically takes five to fourteen days to hatch, with symptoms appearing within three to four days. What starts as a fever and headache can rapidly worsen into something far more severe: brain inflammation, convulsions, mental confusion, and, in the worst cases, coma within just one or two days.

The numbers tell an ugly story. Between 40 and 75 percent of people who contract Nipah die from it. That's an extraordinarily high death rate, far exceeding many other infectious diseases we know. To put it in perspective, even during the worst waves of COVID-19, the death rate was significantly lower.

Yet here's a crucial difference that offers some reassurance that Nipah doesn't spread as easily as COVID-19 did. Each infected person typically passes the virus to fewer than one other person on average. This means while Nipah is deadly for those who catch it, it's unlikely to spark a global pandemic as we experienced in 2020.

A History Written in Outbreaks

The world first learned about Nipah in 1998 when pig farmers and butchers in Malaysia and Singapore began falling ill. The source was traced to infected pigs, and by the time the outbreak was contained, at least 250 people had been infected, and more than 100 had died. Since then, the virus has appeared periodically but repeatedly across South Asia.

Bangladesh has seen multiple outbreaks since 2001, often linked to people drinking raw palm sap that bats had contaminated. In these cases, the virus also spreads through close contact with infected patients, particularly among family members caring for the sick.

India has its own complicated relationship with Nipah. The virus first appeared in West Bengal back in 2001, though it wasn't properly identified until years later. Since 2018, the southern state of Kerala has become what experts now call the world's highest-risk region for the virus, with dozens of deaths recorded.

What's puzzling about the current West Bengal outbreak is that it's happening after decades of relative quiet in that region. The fact that both confirmed cases are healthcare workers at the same hospital strongly suggests they caught the virus from an infected patient who went undiagnosed.

The Treatment Gap

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of Nipah is that we still don't have approved treatments or vaccines. Doctors have been using antiviral drugs like Ribavirin and Remdesivir, which have shown some promise, but their effectiveness remains uncertain. The University of Oxford is currently testing a Nipah vaccine in Bangladesh, but widespread availability is still years away.

Without a vaccine or proven cure, prevention becomes everything. That means the basics of good hygiene, avoiding crowds when sick, washing fruit thoroughly, staying away from date palm sap unless it's been boiled, and keeping bats away from food sources.

For healthcare workers, the stakes are even higher. They need proper protective equipment, good ventilation in treatment areas, and strict protocols to avoid contact with patients' bodily fluids.

A Region on Edge

The anxiety spreading across Asia right now is understandable. Thailand has set up special parking areas at airports for planes arriving from affected regions. Passengers must fill out health forms, and thermal scanners check for fevers. Malaysia, Indonesia, and Nepal have implemented similar measures.

In China, where millions are preparing to travel for the Lunar New Year, social media has erupted with worry. "I don't want to experience another lockdown," one person wrote, echoing the collective trauma of the COVID-19 years. Some have even called for closing travel routes with India.

But experts are urging calm. Unlike COVID-19, Nipah's limited person-to-person transmission means it won't trigger the kind of worldwide shutdowns we endured before. The key is managing severe cases with intensive care and maintaining good public health practices.

Looking Ahead

India's health ministry has reported that all 196 people who had contact with the two infected healthcare workers have tested negative and show no symptoms. The situation, they say, is under control and being closely monitored.

That's encouraging news, but it doesn't erase the underlying concern. Nipah keeps coming back. Whether it's changes in bat populations, deforestation bringing humans closer to wildlife, or climate shifts affecting where bats live and feed, something keeps creating conditions for new outbreaks.

The reality is that in our interconnected world, a virus emerging in one corner can send ripples of fear across entire continents within days. The challenge isn't just treating the sick or preventing transmission. It's also managing the anxiety, building better surveillance systems, and developing the vaccines and treatments we'll need the next time Nipah appears. Because if history has taught us anything, it's that there will be a next time. The question is whether we'll be better prepared when it comes.

. . .

References: