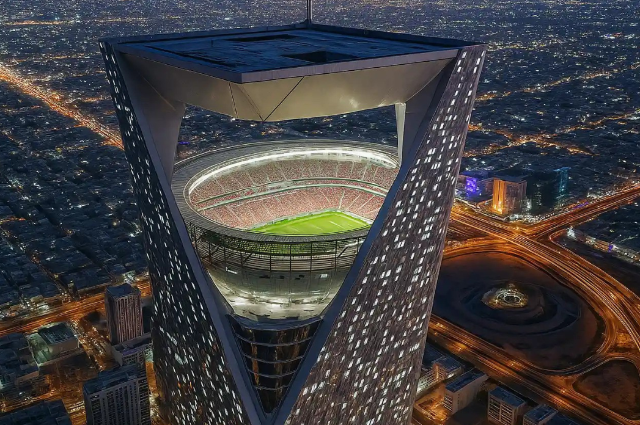

In an age where artificial intelligence can raise entire realities with a few keystrokes, we've just witnessed a masterclass in digital deception. The internet recently erupted over Saudi Arabia's supposed plan to build a "sky stadium" floating 350 meters above the desert, a gravity-defying marvel designed to host matches during the 2034 FIFA World Cup. The concept was audacious, futuristic, and perfectly aligned with the Kingdom's reputation for thinking impossibly big. There was just one big problem: it wasn't real.

What spread across social media like wildfire was not an official announcement from Riyadh, but rather the handiwork of generative AI, polished, convincing, and completely fabricated. The viral images depicted a gleaming stadium suspended between mirrored skyscrapers, part of the ambitious Neom project known as The Line. It looked like something plucked from a science fiction film, which should have been the first clue. Yet thousands bought into the narrative without question, sharing breathless descriptions of solar-powered elevators, 46,000 seats in the clouds, and construction timelines that seemed to materialise from thin air.

The Anatomy of Modern Misinformation

This episode reveals something profound about our current information ecosystem. We live in a world where spectacular lies travel faster than mundane truths, where AI-generated imagery has become sophisticated enough to bypass our critical filters, and where our appetite for the extraordinary makes us willing accomplices in our own deception.

The fake stadium checked all the right boxes for virality. It was visually stunning, technologically ambitious, and tied to Saudi Arabia where a nation that has genuinely been pursuing megaprojects that blur the line between vision and delusion. When a country is already planning to build a 170-kilometer-long mirrored city in the desert, is a floating stadium really that much of a stretch? That's precisely what made this hoax so effective. It operated in the grey zone of plausibility that Saudi Arabia itself has created through its genuine, if sometimes questionable, ambitions.

TikTok users amplified the story with enthusiasm, adding details about renewable energy sources and completion dates. The narrative grew richer with each retelling, acquiring the patina of legitimacy through repetition. Meanwhile, actual Saudi media outlets were discussing something far more conventional, fifteen traditional stadiums, including the King Salman International Stadium in Riyadh with a capacity for over 92,000 spectators. No floating architecture. No mid-air football matches. Just regular, ground-based sporting venues.

The Real Saudi Spectacle

While the Sky Stadium turned out to be fiction, the broader truth about Saudi Arabia's ambitions remains stranger than most fiction. The Kingdom is genuinely attempting to transform its global image through sports, architecture, and sheer financial muscle. Hosting the 2034 World Cup represents not just an athletic achievement but a geopolitical statement and an assertion that oil wealth can purchase relevance, respectability, and a seat at the table of 21st-century power brokers.

This strategy isn't subtle. Saudi Arabia has been aggressively pursuing what critics call "sportswashing" by using high-profile athletic events to distract from uncomfortable questions about human rights, labour conditions, and political freedoms. The World Cup bid is merely the crown jewel in a broader campaign that includes hosting Formula 1 races, bankrolling professional golf tours, and attracting ageing football stars with astronomical salaries.

The Neom project itself, while real, occupies its own peculiar space between aspiration and absurdity. This planned megacity in the desert promises to be carbon-neutral, powered entirely by renewable energy, and built around revolutionary urban design principles. Whether it will ever be completed as envisioned remains an open question. Megaprojects have a way of colliding with reality—budget constraints, engineering challenges, and the simple physics of construction tend to humble even the most ambitious plans.

Lessons in the Age of AI

The Sky Stadium hoax offers important lessons for navigating our increasingly synthetic information landscape. First, spectacular claims require extraordinary verification. When something seems too remarkable to be true, that instinct probably deserves attention. Second, the source matters immensely. No major developer issued press releases. No Saudi official made announcements. The entire narrative emerged from the digital ether, given shape by algorithms and amplified by our collective willingness to believe.

Third, context is crucial. Understanding what Saudi Arabia is actually building and what remains purely aspirational requires looking beyond viral images to established news sources and official channels. The Kingdom is constructing impressive infrastructure, but it's important to distinguish between confirmed projects and internet fantasies.

The Future of Belief

As AI-generated content becomes increasingly sophisticated, these incidents will likely multiply. We're entering an era where seeing is no longer believing, where visual evidence can be manufactured on demand, and where our traditional methods for determining truth are becoming obsolete. The sky stadium wasn't just a hoax it was a preview of challenges ahead.

For now, Saudi Arabia's actual World Cup plans remain ambitious enough without fictional embellishments. Fifteen stadiums across multiple cities will require massive investment, significant infrastructure development, and solutions to genuine challenges like desert heat and water scarcity. These real projects deserve scrutiny and discussion based on facts, not fantasy.

The viral sky stadium will eventually fade from memory, replaced by the next sensational claim that captures our imagination. But the underlying dynamic of our susceptibility to spectacular fiction, especially when it confirms our existing narratives about ambitious nations and impossible projects, will remain. Until we develop better defences against synthetic reality, we'll continue to find ourselves suspended somewhere between earth and illusion, wondering which is which.

. . .

References: