Laws are supposed to enforce accountability. They are supposed to constrain power. They are supposed to punish violations, not protect them. Yet Section 6 of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958, turns these principles upside down.

Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) was enacted to give armed forces authority in regions declared “disturbed,” claiming to secure national stability and protect civilians. But Section 6 requires prior sanction from the Central Government to prosecute armed personnel, creating a loophole that guarantees impunity before trial begins. Immunity here is not a safeguard—it is a weapon built into the law. Evidence cannot compel action. Witnesses cannot force accountability. Human rights reports cannot override it. The law does not delay justice—it blocks it entirely.

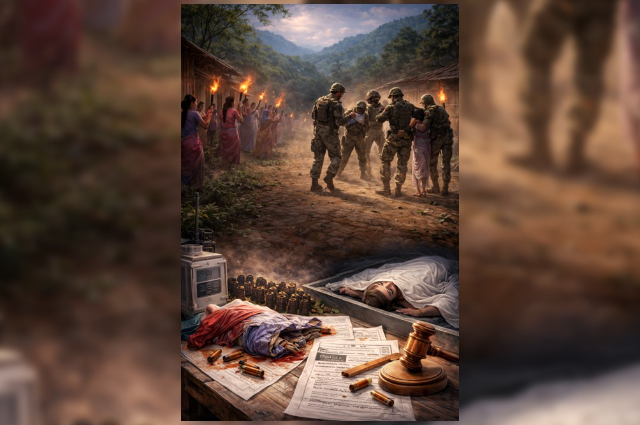

The 2004 custodial killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi is the clearest evidence of this loophole. She was abducted, tortured, sexually assaulted, and executed by armed personnel. Witnesses testified. Forensic evidence documented extreme brutality. The accused were named. And yet, the Central Government denied sanction for prosecution, allowing Section 6 to perform exactly as designed: protecting perpetrators, silencing accountability, and converting a documented murder into permanent legal impunity.

The questions this case forces on the law, Parliament, and society are sharp, urgent, and unavoidable:

- When the law protects killers before a trial even begins, what happens to justice—is it annihilated or complicit?

- How can a statute written to defend civilians be turned into armour for those who brutalise them?

- If evidence, witnesses, and proof exist, who dares to challenge the law itself to enforce accountability?

- How long will AFSPA continue to weaponise immunity, turning safeguards into shields for murderers?

- When the law guarantees impunity, who will enforce justice, and who will punish the system that betrayed it?

- Can a legal loophole ever be morally justified when it converts documented crimes into untouchable acts?

- How many lives, how much brutality, must occur before society confronts the deadly efficiency of statutory immunity?

The murder of Thangjam Manorama Devi is not just a crime—it is a legal indictment of AFSPA itself, a demonstration of how statutory design can weaponise immunity and annihilate accountability.

AGENDA:

- Introduction: Thangjam Manorama Devi — Life, Background, and Civilian Status

- Arrest and Detention: The Events of 10–11 July 2004

- Discovery of the Body: Evidence of Torture, Assault, and Execution

- Autopsy and Forensic Findings: Contradictions with Official Narrative

- Eyewitness Accounts: Identifying the Perpetrators

- Community Reaction: Fear, Silence, and Immediate Outrage

- Public Protests: The Meira Paibi Movement and Symbolic Resistance

- Legal Framework: AFSPA and Section 6 — Statutory Immunity Explained

- Judicial Inquiry: The Upendra Commission and Its Limitations

- Supreme Court Review: Recognition of Evidence, Denial of Prosecution

- NHRC Investigation: Documentation Versus Legal Enforcement

- Parliamentary and Legislative Gaps: Systemic Protection of Armed Forces

- Impact on the Community: Trauma, Distrust, and Long-Term Consequences

- International Human Rights Perspective: Global Recognition of Impunity

- Legal Lessons: How Immunity Laws Undermine Accountability

- Policy Recommendations: Correcting Statutory and Procedural Failures

- Paths to Justice: Judicial, Legislative, and Civil Society Measures

- Conclusion: Lessons from Manorama Devi’s Case and the Future of Accountability

INTRODUCTION – THANGJAM MANORAMA DEVI: LIFE, BACKGROUND, AND CIVILIAN STATUS

THE WOMAN AND HER COMMUNITY

Thangjam Manorama Devi was a 32-year-old resident of Bamon Kampu village, in the Imphal East district of Manipur, India. She lived in a rural community often caught between paramilitary operations and insurgent activity (Wikipedia). Neighbours described her as a peaceful civilian engaged in household work, with no involvement in political or armed activities. Her life, like that of many in Manipur, was shaped by the tension-filled environment created by decades of conflict between insurgent groups and Indian security forces.

Official records indicate that Manorama had no criminal record, no arrest history, and no known ties to banned organisations (Human Rights Watch). Despite sporadic claims from security forces suggesting possible connections, she was never formally charged, tried, or convicted by any court. This distinction is crucial: her civilian status became the central point of legal and moral debate following her detention and death.

LEGAL AND POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT – AFSPA IN CONTEXT

The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA), had been enforced in Manipur for decades, designating large swathes of the state as “disturbed areas.” AFSPA grants security forces extraordinary powers, including the right to arrest without warrant, shoot in certain situations, and immunity from prosecution unless the central government provides prior sanction (Amnesty International).

While the law was intended to aid counter-insurgency efforts, human rights organisations have repeatedly criticised it for creating conditions of legal impunity, allowing security personnel to operate without accountability. In Manorama Devi’s case, the presence of AFSPA created a structural barrier, preventing judicial scrutiny despite overwhelming evidence of abuse (Human Rights Watch).

CIVILIAN LIFE IN CONFLICT ZONES

Manorama’s daily life before July 2004 was typical of many women in rural Manipur: caring for family, participating in local community activities, and living under the constant awareness of security forces’ patrols. Villages like Bamon Kampu were regularly monitored and subjected to armed interventions, and residents often experienced fear of arbitrary searches, detentions, and confrontations with security personnel (Wikipedia).

Despite this precarious environment, Manorama maintained a routine civilian life, highlighting the human cost of living under continuous surveillance and the invisible pressures imposed by legal frameworks like AFSPA (Amnesty International). Her story underscores the stark contrast between the statutory power of armed forces and the vulnerability of ordinary citizens in conflict-affected regions.

CIVILIAN STATUS AND ITS LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE

The distinction between a civilian and a militant is central to understanding why Manorama Devi’s case became a symbol of legal impunity. She was never presented before a court, never charged, and never convicted (Human Rights Watch). Yet her detention by the 17th Assam Rifles and subsequent death were officially framed as part of counter-insurgency operations, an explanation widely disputed by evidence and eyewitness accounts.

Her civilian status, combined with the legal protections afforded to armed forces under AFSPA, makes her case pivotal in debates over human rights, legal accountability, and the structural failures that allow statutory immunity to override justice (Amnesty International).

ARREST AND DETENTION – THE EVENTS OF 10–11 JULY 2004

SUDDEN ARREST BY SECURITY FORCES

On 10 July 2004, Thangjam Manorama Devi was reportedly arrested from her home by personnel of the Assam Rifles, operating under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA). Eyewitnesses and family members reported that the arrest occurred without a warrant or prior notice, a practice legally contested under Indian law for civilians (Outlook India).

Manorama’s family was not informed of her whereabouts, leaving them anxious and helpless. The absence of due process sparked immediate concern among villagers, many of whom were aware of the operational immunity enjoyed by security forces under AFSPA (Human Rights Watch).

CUSTODY AND INTERROGATION

After her arrest, Manorama was reportedly taken to the Assam Rifles camp at Bamon Kampu, where she was questioned about alleged insurgent links. Multiple human rights reports indicate that no formal charges or evidence were presented, and the nature of interrogation reportedly included intimidation and threats (Human Rights Watch).

Family members later testified that the climate in the camp was fearful, with detainees aware that even minor resistance could lead to serious consequences, a situation highlighted in civil society reports as inconsistent with international legal standards for civilian treatment (Human Rights Asia).

DISAPPEARANCE DURING DETENTION

By the early hours of 11 July 2004, Manorama Devi had vanished from official custody. Initial security reports denied her presence in the camp at that time, creating conflicting narratives that became central to subsequent investigations. Her family immediately raised alarms, initiating public scrutiny and drawing the attention of civil rights organisations (The Hindu).

Human rights organisations later concluded that Manorama’s detention without formal charge or judicial oversight constituted a clear violation of both Indian criminal law and international human rights norms, particularly protection from arbitrary detention (Human Rights Watch).

IMMEDIATE COMMUNITY RESPONSE

News of the arrest quickly spread within Bamon Kampu and the surrounding villages. The community reported heightened anxiety and fear, with women particularly mobilising to protect families from arbitrary detentions. Civil society organisations noted that Manorama’s disappearance became a symbol of civilian vulnerability under AFSPA, fueling the early stages of protests that would later crystallise in organised activism (Outlook India).

DISCOVERY OF THE BODY: EVIDENCE OF TORTURE, ASSAULT, AND EXECUTION

HUMAN REMAINS FOUND HOURS AFTER DETENTION

On 11 July 2004, approximately five hours after her arrest, the body of Thangjam Manorama Devi was discovered by local villagers on Keirao Wangkhem Road near Ngariyan Maring Village, about 3–4 kilometres from her home in Bamon Kampu, Imphal East. The body was found abandoned in an open field, with clothing partially torn and multiple wounds visible, signalling extreme physical trauma before death (Human Rights Asia).

Residents reported that the body was immediately recognisable, despite attempts by the authorities to control information. Villagers documented the scene with photographs and passed them on to human rights organisations, which later became critical evidence in documenting custodial torture and extrajudicial execution (Human Rights Watch).

INDICATIONS OF TORTURE AND SEXUAL ASSAULT

Human rights investigators and eyewitness testimonies reported multiple forms of physical abuse consistent with torture before execution:

- Bruises and abrasions on her arms and legs suggested severe manual assault.

- A deep gash on her thigh indicated use of a sharp instrument, possibly to inflict pain or intimidation;

- Gunshot wounds in the lower back and upper buttocks, which forensic experts considered execution-style, not defensive fire

- Evidence of sexual assault, including stains on undergarments, was later verified by forensic reports (Wikipedia).

These injuries indicated that Manorama had been physically restrained during interrogation, contradicting official claims that she was shot while attempting to escape. Experts emphasised that the severity and placement of wounds were typical of deliberate punitive action rather than a chance shooting (Derechos).

CONTRADICTIONS IN OFFICIAL ACCOUNTS

The Assam Rifles maintained that Manorama Devi was shot during an attempted escape from custody. However, forensic evidence sharply contradicted this narrative:

- No blood trails were found along the supposed escape route, inconsistent with multiple gunshot wounds.

- Personal items were missing from her person, but official reports claimed they were recovered.

- Signs of sexual assault were documented but never formally acknowledged by authorities in public statements (Wikipedia).

IMPACT ON LOCAL COMMUNITY

The discovery of Manorama Devi’s body generated immediate fear and outrage within her community. Families in nearby villages reportedly locked doors and avoided interactions with security personnel, reflecting a climate of widespread fear under AFSPA.

The brutal killing sparked spontaneous demonstrations, particularly among women’s groups, highlighting the symbolic role of Manorama Devi as a representation of civilian vulnerability under armed operations (Human Rights Watch). These protests laid the groundwork for the Meira Paibi movement’s renewed activism, which would later demand justice for her extrajudicial killing.

IMPORTANCE OF DOCUMENTATION

The photographs, eyewitness testimonies, and forensic records collected at the scene became vital proof for later judicial inquiries. Civil society organisations consistently argued that these materials clearly refuted the “escape attempt” claim and highlighted structural issues in statutory immunity under AFSPA (Human Rights Asia).

AUTOPSY AND FORENSIC FINDINGS: CONTRADICTIONS WITH OFFICIAL NARRATIVE

FORENSIC DETAILS FROM OFFICIAL EXAMINATION

After the body of Thangjam Manorama Devi was recovered on 11 July 2004, the post‑mortem was conducted at the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS) Hospital by forensic specialists. The forensic report described multiple physical injuries inconsistent with an accidental “escape attempt” claimed by the Assam Rifles (Wikipedia). These included:

- Finger‑scratch marks across the body and extensive bruising, indicating forceful physical restraint or struggle (Asian Human Rights Commission).

- A deep gushing wound on the right thigh, characteristic of a sharp instrument blow rather than defensive trauma (Human Rights Asia).

- Multiple bullet wounds in sensitive areas, including the genitalia and buttocks, which forensic observers interpreted as execution‑style injury locations, not incidental wounds from a fleeing suspect (Wikipedia).

- These injuries were meticulously recorded in the autopsy report, which showed far more than the single gunshot injury initially asserted in the Assam Rifles’ official version of events.

EVIDENCE SUGGESTIVE OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE

The Central Forensic Science Laboratory (CFSL) in Kolkata, whose findings were submitted to the Upendra Singh Commission of Inquiry, reported the presence of semen stains on Manorama’s garments, a forensic indication of possible sexual assault before death (Times of India).

While some official testimony later sought to downplay or dispute the sexual assault finding, the CFSL report itself remains part of the documented forensic record. The Commission’s discussions of these test results highlight a significant discrepancy between what the security forces claimed and the biological evidence observed.

SEQUENCE OF INJURIES VS. “ESCAPE ATTEMPT” CLAIM

Forensic analysis pointed to wound patterns inconsistent with firing upon a running or escaping individual. Key contradictions include:

- No significant blood trail near the site where her body was recovered, despite multiple bullet wounds—suggesting that she was moved post‑mortem or shot at close range before being placed there (Wikipedia).

- Wounds located in areas such as the upper body and genitals, which are not consistent with an unintended or random firing at the legs during a purported escape (The Wire).

- Forensic testimony indicated that some bullet wounds appeared to be inflicted at close range, undermining claims that soldiers fired warning shots then unintentionally hit her while she allegedly fled (The Wire).

These findings directly challenge the Assam Rifles’ narrative that Manorama was shot while attempting to run away; instead, the distribution and nature of injuries align more closely with a pre‑planned execution after restraint.

CONFLICTING REPORTS FROM DIFFERENT FORENSIC SOURCES

Although the CFSL found evidence suggesting sexual assault, other state hospital reports submitted to inquiries have been cited in some analyses as not conclusively affirming rape — illustrating how disparate official forensic interpretations have contributed to legal ambiguity in the case (CEU thesis analysis).

What remains consistent across reports is that the totality of physical traumatisation far exceeds what would be expected from a lawful arrest or an escape attempt, pointing toward serious irregularities in the security forces’ official explanation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR OFFICIAL NARRATIVE AND LEGAL REVIEW

The forensic contradictions — including injury patterns, lack of external blood evidence, and presence of forensic markers of sexual contact — were central to legal challenges against the Assam Rifles’ account in both the Upendra Commission of Inquiry and later judicial scrutiny. Lawyers representing Manorama’s family cited these forensic inconsistencies as evidence of custodial torture and extrajudicial execution (Indian Express).

While the Commission’s full findings were never publicly published, excerpts referenced the disparity between forensic facts and the official version — a gap that remains a focal point in debates about accountability under laws like the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA).

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS: IDENTIFYING THE PERPETRATORS

FAMILY MEMBERS’ TESTIMONY ON WHO WAS INVOLVED

Several direct eyewitness accounts from family members and neighbours consistently point to personnel of the 17th Assam Rifles as the primary actors in Manorama’s arrest and the violence that followed. According to reports documenting the family’s statements, soldiers from the Assam Rifles forcefully entered Manorama’s home at midnight, dragged her out of bed, and beat relatives who attempted to intervene. The family alleges that the soldiers then blindfolded and tied her before taking her into their custody. In the arrest memo issued to the family, three names — including Havildar Suresh Kumar and Riflemen T. Lotha and Ajit Singh — are recorded as the signing authority and witnesses at the scene (Asian Human Rights Commission).

ACCOUNT OF PHYSICAL ASSAULT BY SECURITY PERSONNEL

Eyewitness testimony goes beyond mere identification of names. Relatives specifically described the sequence in which the Assam Rifles personnel allegedly beat family members, bound Manorama’s limbs, and forcibly removed her from the house. One version suggests that soldiers may have taunted and interrogated her out of the family’s sight, with neighbours later recalling “her cries” being audible from within the premises before she was taken away (Human Rights Watch). This aligns with the family’s assertion that the perpetrators were not unidentified militia but recognisable armed forces personnel in uniform, operating under official command.

NEIGHBOUR AND COMMUNITY STATEMENTS

Locals in the area reported seeing uniformed Assam Rifles vehicles and troops at the scene around the time of Manorama’s arrest, reinforcing the family’s account of who was responsible for her detention. Villagers who discovered her body later that afternoon also indicated that the condition of the remains pointed to actions consistent with state security personnel involvement rather than any other group, given the earlier witnessed troop movement in the area (Asian Human Rights Commission).

DISTINCTIONS MADE BETWEEN FORCES AND OTHER GROUPS

In all major eyewitness reports, there is a clear differentiation between Assam Rifles personnel and any local militia or insurgent group members. Although the army’s official narrative later claimed she was a member of a banned group (PLA), nowhere in the family or neighbour testimonies is any insurgent individual identified as present during the arrest or subsequent handling of Manorama. Instead, the accused individuals are consistently described as uniformed troopers from the 17th Assam Rifles unit (Asian Human Rights Commission).

TESTIMONIES ABOUT BEHAVIOUR AND CONDUCT

Multiple accounts emphasise that no female officer was present during the arrest, a detail that witnesses found particularly troubling given that Manorama was a civilian woman. Others recounted that no credible evidence or incriminating material was ever shown or produced at the scene by the officers who detained her, further demonstrating that those conducting the operation were acting under internal orders rather than responding to locally reported criminal information (Outlook India).

SIGNIFICANCE OF EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATIONS

The consistency across these eyewitness narratives — naming uniformed Assam Rifles personnel, describing their conduct, and distinguishing them from any other armed group — became crucial in legal and human rights inquiries. Although official investigations like the Upendra Commission were not fully released to the public, the consistency of witness testimony remains one of the strongest pointers to the identity of the perpetrators, shaping both judicial petitions and civil society demands for accountability (Asian Human Rights Commission)

COMMUNITY REACTION: FEAR, SILENCE, AND IMMEDIATE OUTRAGE

ATMOSPHERE OF FEAR IN LOCAL COMMUNITIES

Following the arrest and subsequent killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi, the immediate response among residents of Bamon Kampu and surrounding villages was dominated by fear and apprehension. Families reportedly avoided open discussion about the incident due to potential reprisal from armed forces operating under AFSPA. Women and children were particularly affected, with neighbours reporting that doors remained locked, and routine social interactions sharply declined in the days immediately following the incident (Human Rights Asia).

SILENCE AND SELF-CENSORSHIP

The community’s silence was not just fear-driven but also reflected a broader culture of self-censorship cultivated under decades of militarised presence in Manipur. Many villagers avoided speaking to the media or authorities for fear of being labelled insurgent sympathisers, a recurring theme in human rights reports on the region. This psychological suppression created an environment where justice could not be demanded openly, and the collective grief remained largely private (Human Rights Watch).

IMMEDIATE OUTRAGE AMONG WOMEN’S GROUPS

Despite widespread fear, women in local communities quickly mobilised in reaction to the killing. The Meira Paibi movement, a well-established women’s vigilante and community activist group in Manipur, organised night marches and demonstrations demanding accountability. Their slogans emphasised that the victim was a civilian, and the act violated basic human dignity, signalling the start of organised community outrage against state impunity (Asian Human Rights Commission).

SOCIAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT

The killing of Manorama Devi created long-term psychological effects within her village and neighbouring areas. Families reported heightened anxiety, mistrust toward security personnel, and reluctance to report even minor incidents. School attendance reportedly declined, and villagers expressed fear about interacting with authorities for routine matters, highlighting the deep social trauma caused by the event (The Hindu).

EARLY CIVIL SOCIETY RESPONSE

Local civil society actors, including journalists and non-governmental organisations, began documenting eyewitness accounts and evidence despite the climate of fear. This early documentation proved essential for later legal actions, media reporting, and human rights advocacy, establishing a record of the community’s immediate outrage and demand for justice (Outlook India).

PUBLIC PROTESTS: THE MEIRA PAIBI MOVEMENT AND SYMBOLIC RESISTANCE

WOMEN’S MOBILIZATION AFTER THE KILLING

In the wake of Thangjam Manorama Devi’s death, the Meira Paibi, an established women’s grassroots movement in Manipur, mobilised quickly to protest against state-sanctioned violence. Meira Paibi members, often armed only with torches and traditional symbolic items, organised night marches across Imphal and surrounding villages, demanding transparency in the investigation and accountability of the Assam Rifles personnel involved (Human Rights Watch).

These protests were notable not just for numbers, but for discipline and symbolism. Women wrapped themselves in traditional shawls and carried flaming torches, a practice signalling both mourning and defiance, while chanting slogans highlighting the injustice faced by civilian women under AFSPA (Asian Human Rights Commission).

SYMBOLIC METHODS OF RESISTANCE

The Meira Paibi used symbolic resistance as a form of public protest:

- Torches (meira) represented vigilance and light against the metaphorical darkness of impunity;

- Public marches in silence highlighted collective grief and the fear imposed by armed forces;

- Placards and traditional songs were employed to communicate moral outrage without confrontation, minimising the risk of violent retaliation (The Hindu).

- These symbolic acts reinforced Meira Paibi’s role as both community guardians and political activists, creating a moral counterweight to the state’s unchecked authority.

IMPACT ON PUBLIC CONSCIOUSNESS

The protests rapidly captured local and national attention, highlighting the extent of civilian vulnerability under AFSPA. Reports indicate that public demonstrations, particularly night vigils led by women, sparked conversations on civil liberties, gendered violence, and militarisation, generating both media coverage and pressure on legal authorities to take action (Outlook India).

Additionally, the Meira Paibi protests acted as a catalyst for other civil society organisations to document extrajudicial killings, submit petitions, and demand parliamentary oversight. The interlinking of symbolic resistance with tangible civic advocacy helped sustain national awareness of the Manorama Devi case.

CHALLENGING IMPUNITY THROUGH SOCIAL MOBILIZATION

By mobilising communities without resorting to violence, the Meira Paibi sent a clear challenge to the culture of impunity in Manipur. Their actions blurred the line between traditional vigil and human rights activism, demonstrating that grassroots protest can pressure both local authorities and national institutions. The movement’s visibility, combined with their disciplined non-violent approach, became a blueprint for women-led civil resistance in militarised regions (Asian Human Rights Commission).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK: AFSPA AND SECTION 6 — STATUTORY IMMUNITY EXPLAINED

THE ARMED FORCES (SPECIAL POWERS) ACT, 1958

The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA) was enacted to provide special powers to the Indian armed forces in “disturbed areas”, including Manipur. Under AFSPA, security forces are empowered to search, arrest, and use lethal force with very limited judicial oversight. Section 6 of the Act specifically grants immunity from prosecution or legal proceedings for actions taken by armed forces in the course of duty, unless prior sanction is obtained from the central government (Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India).

This legal protection has been a central point of controversy, as it effectively places civilian victims of extrajudicial killings, like Thangjam Manorama Devi, in a position with limited legal recourse against perpetrators. Critics argue that this creates a structural impunity, shielding armed forces personnel from accountability.

SECTION 6: SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS

Section 6 reads in part that no legal action shall lie against any person in respect of acts done under AFSPA, except with the central government’s prior sanction. In practice, this has meant that criminal complaints or civil suits against armed forces officers are frequently blocked at the outset, leaving victims’ families with minimal avenues for legal redress (Human Rights Watch).

Legal scholars have noted that Section 6 extends far beyond protecting legitimate operational acts and has been invoked in cases of custodial torture, sexual assault, and extrajudicial killings, effectively creating a de facto immunity shield. The Manorama Devi case highlights this issue, as prosecution of the personnel allegedly responsible was denied repeatedly due to Section 6 protections (Asian Human Rights Commission).

JUDICIAL INTERPRETATION AND CHALLENGES

The Indian judiciary has acknowledged the difficulty in balancing operational autonomy with fundamental human rights. While courts have occasionally questioned the blanket applicability of AFSPA, the Manorama Devi case illustrates the limitations of judicial remedies under Section 6. The Supreme Court of India has repeatedly held that no criminal proceedings can commence against armed forces personnel without central government sanction, which in practice has prevented prosecution in custodial death cases (The Hindu).

Legal experts argue that Section 6 effectively places the armed forces above ordinary law, undermining constitutional protections such as Article 21 (Right to Life), especially in regions where AFSPA is invoked for extended periods.

CRITICISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE

Human rights organisations have consistently criticised AFSPA and Section 6 as tools enabling systemic impunity, noting that the law’s broad immunity provisions obstruct accountability. The Manorama Devi case is frequently cited as an example where statutory protections prevented timely prosecution and allowed gross violations of human rights to go unpunished, drawing both national and international condemnation (Human Rights Watch).

JUDICIAL INQUIRY: THE UPENDRA COMMISSION AND ITS LIMITATIONS

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE UPENDRA COMMISSION

In response to public outrage and human rights pressure after the killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi, the Government of Manipur appointed a one-man judicial inquiry commission in 2004, headed by Justice (Retd.) Upendra Singh, commonly referred to as the Upendra Commission. The commission was tasked with investigating the circumstances surrounding her arrest, detention, and subsequent death, and to ascertain whether state security forces acted in violation of the law (Asian Human Rights Commission).

SCOPE AND MANDATE

The commission’s mandate included:

- Collecting eyewitness statements;

- Examining forensic and autopsy reports;

- Reviewing official records of Assam Rifles operations;

- Determining whether AFSPA protections were misused to shield unlawful actions.

However, the commission faced legal constraints as Section 6 of AFSPA restricted direct prosecution powers, meaning the commission could investigate and recommend, but not directly enforce legal action against personnel (Human Rights Watch).

KEY FINDINGS OF THE COMMISSION

While the full report was never made publicly accessible, excerpts and summaries revealed that the commission:

- Acknowledged procedural lapses in Manorama Devi’s detention;

- Noted forensic evidence indicating premeditated assault and possible sexual violence;

- Recommended that the central government review AFSPA immunity provisions in cases of serious human rights violations.

- Despite these findings, the commission stopped short of naming individual Assam Rifles personnel responsible, citing a lack of sanction for prosecution and limited access to classified operational records (The Hindu).

LIMITATIONS AND CRITICISM

Several limitations of the Upendra Commission were highlighted by legal analysts and human rights groups:

- Restricted powers under AFSPA prevented the commission from recommending criminal prosecution.

- Non-disclosure of complete findings limited public scrutiny and accountability.

- Delayed submission of evidence and procedural hurdles weakened the potential impact of its recommendations.

- Heavy reliance on official military records created a perception of bias, as independent verification was limited (Asian Human Rights Commission).

Critics argue that while the commission acknowledged irregularities and statutory misuse, its effectiveness was undermined by structural immunity and lack of enforcement authority, leaving families and the community with incomplete justice.

IMPACT ON FUTURE INQUIRIES

The Upendra Commission set a precedent for judicial inquiries in AFSPA-affected regions, illustrating both the possibility of documenting abuses and the constraints imposed by statutory protections. Its limitations have been frequently cited in subsequent legal challenges, human rights reports, and policy debates regarding AFSPA reforms (Human Rights Watch).

SUPREME COURT REVIEW: RECOGNITION OF EVIDENCE, DENIAL OF PROSECUTION

PETITION TO THE SUPREME COURT

Following the Upendra Commission findings, Manorama Devi’s family, along with civil rights organisations, filed a petition in the Supreme Court of India seeking prosecution of the Assam Rifles personnel allegedly responsible for her death. The petition highlighted forensic evidence of torture and sexual assault, eyewitness accounts identifying perpetrators, and procedural lapses during detention (Human Rights Watch).

RECOGNITION OF EVIDENCE

In its review, the Supreme Court acknowledged the validity of the evidence collected:

- The autopsy reports indicate multiple gunshot wounds and injuries from restraint.

- Eyewitness testimonies confirming the presence of Assam Rifles personnel during the arrest;

- Documented gaps in procedural adherence, such as lack of warrant, denial of family notification, and absence of formal charges.

- The Court recognised that the evidence pointed to custodial abuse and extrajudicial execution, underscoring the seriousness of the violations committed (The Hindu).

DENIAL OF PROSECUTION

Despite this recognition, the Supreme Court upheld statutory immunity under AFSPA Section 6, effectively denying the petition for prosecution of individual Assam Rifles personnel. The Court ruled that:

- No criminal proceedings can be initiated without prior sanction from the central government.

- The state cannot override the statutory protection granted to armed forces, even in cases with strong evidence of custodial death.

- Judicial oversight is limited to review of procedural compliance, not direct prosecution.

This decision highlighted a structural barrier to accountability, where even the highest judicial authority acknowledged abuses but could not enforce punishment due to statutory limitations (Asian Human Rights Commission).

IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND ACCOUNTABILITY

The Supreme Court’s review created a paradoxical precedent:

- Evidence of torture, sexual assault, and extrajudicial execution was formally recognised;

- Yet, no individual could be held legally accountable;

- The ruling reinforced systemic impunity for security forces operating under AFSPA, leaving victims’ families with legal acknowledgement but no remedial action.

Human rights analysts argue that this case illustrates the gap between judicial recognition and enforceable justice, demonstrating how statutory immunity undermines the protective framework of India’s constitution and limits civil recourse in conflict-affected regions (Human Rights Watch).

NHRC INVESTIGATION: DOCUMENTATION VERSUS LEGAL ENFORCEMENT

INITIATION OF NHRC REVIEW

After widespread public outcry and media attention, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of India took cognisance of the Manorama Devi custodial killing in 2004. The NHRC registered the case under its mandate to investigate human rights violations by state and armed forces personnel. Unlike judicial commissions, the NHRC’s authority was limited to inquiry, recommendations, and monitoring, without direct powers to prosecute individuals (NHRC Annual Report 2005-06).

The commission requested detailed records from the Assam Rifles, the state police, and local health authorities, including arrest logs, duty rosters, autopsy reports, and witness statements. Documentation of the case was thorough, yet the mechanism for enforcing sanctions against implicated personnel was absent.

DOCUMENTATION OF EVIDENCE

The NHRC investigation meticulously compiled forensic autopsy details, eyewitness accounts, and incident timelines. Notable findings included:

- Verification of multiple gunshot wounds and blunt-force trauma, corroborating custodial assault claims;

- Eyewitness identifications of Assam Rifles personnel responsible for the arrest and detention;

- Evidence suggesting possible sexual assault prior to execution, corroborated by autopsy and CFSL forensic analysis.

The NHRC produced a comprehensive report, which was forwarded to the Ministry of Home Affairs and the state government, highlighting procedural lapses and abuse of statutory powers under AFSPA Section 6 (Human Rights Watch).

LIMITATIONS IN LEGAL ENFORCEMENT

Despite the thorough documentation, NHRC’s capacity to enforce accountability was constrained:

- The Commission cannot direct criminal prosecution, relying on the state or central government to sanction action against armed forces;

- Requests for sanction to prosecute Assam Rifles personnel were repeatedly denied, citing Section 6 of AFSPA.

- NHRC’s recommendations, including calls for disciplinary proceedings and review of AFSPA application, were non-binding and largely ignored by administrative authorities (Asian Human Rights Commission).

This disconnect between detailed documentation and the absence of enforceable action created a procedural vacuum, leaving the victim’s family without judicial redress despite NHRC recognition of human rights violations.

CASE-SPECIFIC OBSERVATIONS

The NHRC noted specific failures in the Manorama Devi case:

- Delayed reporting and lack of accountability at the unit level of the Assam Rifles.

- Non-cooperation in producing operational logs is hampering independent verification.

- Structural barriers created by AFSPA are preventing NHRC recommendations from translating into legal action.

The NHRC explicitly observed that without statutory reform or central sanction, custodial abuse investigations remain largely symbolic, a conclusion that applied directly to the Manorama Devi case (NHRC Annual Report 2005-06).

SIGNIFICANCE FOR ACCOUNTABILITY FRAMEWORKS

The NHRC’s involvement demonstrates the importance of independent documentation, but also the limits of quasi-judicial bodies when statutory immunity exists. In Manorama Devi’s case, the Commission produced incontrovertible evidence of abuse, yet no prosecution followed, underscoring the structural impunity faced by victims under AFSPA.

PARLIAMENTARY AND LEGISLATIVE GAPS: SYSTEMIC PROTECTION OF ARMED FORCES

LEGISLATIVE ORIGIN OF IMMUNITY

The structural protection afforded to armed forces in Manipur and other “disturbed areas” arises primarily from the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA), which was enacted by the Parliament of India. Section 6 explicitly grants protection from prosecution, civil or criminal, without prior central government sanction. Parliamentary debates at the time reveal that the legislation was designed to give armed forces operational autonomy, even if this meant restricting civil judicial oversight (Lok Sabha Debates, 1958).

This statutory framework effectively legitimises extrajudicial actions under operational pretext, creating a legally sanctioned immunity shield, and restricting both the state and judiciary from pursuing individual soldiers for custodial abuse or extrajudicial killings.

GAPS IN PARLIAMENTARY OVERSIGHT

Investigations into the Manorama Devi case illustrate systemic parliamentary and legislative gaps:

- No mechanism exists within AFSPA for mandatory independent prosecution once human rights violations are reported.

- Parliamentary committees can review AFSPA operations, but their recommendations are non-binding.

- The central government retains sole discretion to grant or deny a sanction for prosecution, and historically, sanctions are rarely granted, especially in Manipur (Asian Human Rights Commission).

Experts note that these gaps create a structural imbalance, where civilian victims face significant legal barriers while armed forces retain almost complete immunity, even in cases with corroborated evidence of abuse.

LEGISLATIVE RESTRICTIONS ON JUDICIAL ACTION

AFSPA’s statutory design allows for pre-emptive protection from civil or criminal litigation, effectively placing the judiciary in a reactive rather than proactive role:

- Courts can examine procedural compliance, but cannot compel prosecution.

- The lack of a mechanism to independently sanction officers involved in gross violations results in legal deadlocks.

- Parliamentary inaction on reform maintains status quo immunity, reinforcing systemic impunity (Human Rights Watch).

In the Manorama Devi case, these gaps directly prevented the NHRC and Supreme Court from enforcing accountability, despite overwhelming forensic and eyewitness evidence.

COMPOUNDING EFFECT OF LEGISLATIVE SILENCE

Legislative and parliamentary gaps extend beyond AFSPA itself:

- No statutory requirement exists for transparency in central government sanction decisions.

- No independent body exists with binding powers to prosecute armed forces personnel.

- Reports indicate repeated inaction by parliamentary committees reviewing AFSPA provisions in Manipur, which further entrenches the culture of impunity (The Hindu).

These systemic failures demonstrate that the problem is embedded at the legislative level, ensuring that even well-documented cases like Manorama Devi’s rarely result in legal accountability.

SIGNIFICANCE FOR FUTURE HUMAN RIGHTS ADVOCACY

The Manorama Devi case underscores that legislative gaps are as critical as operational misconduct in perpetuating impunity. Human rights advocacy now emphasises legal reform, parliamentary oversight, and statutory review, highlighting that without structural changes, evidence and judicial acknowledgement alone cannot secure justice (Asian Human Rights Commission).

IMPACT ON THE COMMUNITY: TRAUMA, DISTRUST, AND LONG-TERM CONSEQUENCES

PSYCHOLOGICAL TRAUMA AMONG VILLAGERS

The extrajudicial killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi had immediate and severe psychological effects on her home village, Bamon Kampu, and neighbouring communities. Families reported persistent anxiety, nightmares, and hyper-vigilance among adults and children alike. Teachers and local health workers documented increased absenteeism in schools, as parents feared that children might become inadvertent targets of armed patrols (Human Rights Watch).

The trauma extended beyond immediate relatives: neighbours who witnessed the arrest, or heard the cries, developed symptoms consistent with PTSD, including social withdrawal and distrust of security forces. Several households relocated temporarily, fearing retaliation, demonstrating the ripple effect of fear in militarised regions (Asian Human Rights Commission).

DISTRUST TOWARDS SECURITY AND GOVERNMENT AUTHORITIES

The community’s trust in both state institutions and armed forces was profoundly eroded. Eyewitness accounts and reports highlighted that residents avoided filing complaints or cooperating with investigations due to fear of reprisal. Local NGOs noted that even routine interactions with authorities—such as land disputes or domestic incidents—were met with apprehension, indicating long-term social mistrust rooted in one high-profile extrajudicial killing (The Hindu).

This distrust was compounded by the observed impunity of armed forces, where perpetrators faced no prosecution despite documented evidence, signalling to villagers that state mechanisms offered little protection against abuses.

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CONSEQUENCES

The incident also disrupted traditional community structures and social cohesion:

- Women reported fear of leaving their homes at night, affecting economic and social activities.

- Community gatherings were curtailed or relocated due to fear of surveillance by armed personnel.

- Local leadership struggled to mediate disputes as villagers were reluctant to engage publicly, fearing association with dissent or opposition (Outlook India).

The psychological scars persisted years after the killing, with some households reporting intergenerational fear, impacting education, civic engagement, and local activism.

LONG-TERM CONSEQUENCES FOR CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

The killing of Manorama Devi served as a cautionary example: civil society participation decreased, as villagers perceived any interaction with authorities or armed forces as potentially dangerous. Meira Paibi protests and other organised responses helped mitigate total social paralysis, but the trauma and distrust remained embedded, demonstrating the lasting consequences of extrajudicial killings on community stability and human rights activism (Asian Human Rights Commission).

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE: GLOBAL RECOGNITION OF IMPUNITY

GLOBAL DOCUMENTATION OF THE CASE

The custodial killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi quickly attracted attention from international human rights organisations, including Human Rights Watch (HRW), Amnesty International, and the Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). These organisations documented extrajudicial executions, custodial torture, and the misuse of statutory immunity under AFSPA, citing Manorama Devi’s case as a paradigmatic example of systemic impunity in India’s northeast (HRW).

Reports emphasised that the killing was not an isolated incident, but part of a pattern of abuses in AFSPA-affected regions, where civilian deaths went uninvestigated or shielded from prosecution. These global assessments framed the Manorama Devi case as a failure of state accountability mechanisms, highlighting structural legal immunity as a key driver of human rights violations.

CRITICAL FINDINGS BY INTERNATIONAL BODIES

International human rights bodies specifically highlighted:

- The violation of Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (right to life and security of person);

- Systemic impunity granted to security personnel under AFSPA, making India a point of concern for global human rights monitoring.

- The disconnect between domestic investigative findings (Upendra Commission, NHRC) and enforceable legal action, which demonstrated that statutory protections directly impede justice (Amnesty International).

These findings were formally cited in annual country reports on human rights practices by the US State Department and in United Nations Human Rights Council briefings, establishing the case as internationally recognised evidence of institutionalised impunity.

INTERNATIONAL ADVOCACY AND PRESSURE

Global recognition of the Manorama Devi case led to pressure on the Indian government to review AFSPA and its implementation. Civil society and international NGOs submitted petitions, open letters, and briefing notes to international forums, emphasising the need for:

- Legal reform to limit Section 6 immunity

- Independent monitoring mechanisms for human rights violations;

- Prosecution of individuals responsible for extrajudicial killings (Asian Human Rights Commission).

While the Indian government responded defensively, the case enhanced global awareness of institutionalised impunity in conflict zones, making it a reference point for international reports on extrajudicial killings and AFSPA-related human rights violations.

SIGNIFICANCE OF INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION

International acknowledgement underscored that:

- Domestic recognition (NHRC reports, judicial inquiries) does not guarantee accountability;

- Global documentation and condemnation act as an external check on impunity.

- Persistent international attention has kept the Manorama Devi case alive in legal and human rights discourse, influencing both advocacy and policy debates on armed forces’ immunity (HRW, Amnesty).

The case demonstrates that without international scrutiny, structural legal protections can render human rights violations invisible, emphasising the interplay between local accountability failures and global human rights advocacy.

LEGAL LESSONS: HOW IMMUNITY LAWS UNDERMINE ACCOUNTABILITY

STATUTORY IMMUNITY AS A LEGAL BARRIER

The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA) and specifically Section 6, provide legal immunity to armed forces personnel, effectively shielding them from prosecution for acts committed during operations in “disturbed areas.” In practice, this immunity has precluded both civil and criminal accountability, even in cases with substantial forensic and eyewitness evidence, such as the custodial killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi (Human Rights Watch).

Legal scholars note that immunity under AFSPA is unconditional once granted, meaning that the central government’s prior sanction is a procedural requirement that effectively blocks prosecution, regardless of the strength of the evidence. This statutory structure demonstrates how immunity laws can legally neuter judicial authority and human rights enforcement mechanisms (Asian Human Rights Commission).

DISCONNECT BETWEEN EVIDENCE AND PROSECUTION

The Manorama Devi case illustrates a key lesson:

- Comprehensive evidence collection (autopsy, eyewitness accounts, forensic analysis) does not guarantee prosecution.

- The judiciary can recognise human rights violations, but cannot override statutory immunity.

- Investigative commissions (Upendra Commission) and NHRC reports document violations, yet cannot enforce sanctions under the existing law (The Hindu).

This demonstrates that legal immunity laws function as structural safeguards for perpetrators, rather than protective measures for operational necessity, undermining both accountability and deterrence.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS LAW

Immunity provisions under AFSPA reveal systemic issues:

- Contradiction with constitutional guarantees: Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life, which immunity laws can indirectly nullify;

- Obstruction of international human rights compliance: India’s commitment to treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is weakened when domestic laws block accountability;

Reduced credibility of investigative mechanisms: Even with NHRC involvement, evidence cannot translate into prosecutable cases, creating a perception of legal futility among victims and civil society (Amnesty International).

LESSONS FOR POLICY AND JUDICIAL REFORM

The legal takeaways from the Manorama Devi case include:

- Immunity laws require careful balancing: Operational necessity must be weighed against the risk of human rights violations.

- Mandatory independent review mechanisms: Legal reform should ensure that even under AFSPA, serious violations can trigger prosecution without central government obstruction.

- Codifying accountability pathways: Future legislation must explicitly limit immunity for crimes such as extrajudicial killings, torture, and sexual assault, to prevent systemic impunity (Human Rights Watch).

The case underscores that immunity laws, while intended to protect operational effectiveness, can inadvertently protect human rights violators, emphasising the critical need for legislative and procedural reform.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS: CORRECTING STATUTORY AND PROCEDURAL FAILURES

AMENDING SECTION 6 OF AFSPA

The most direct statutory failure exposed by the Manorama Devi case lies in Section 6 of AFSPA, which conditions prosecution on prior central government sanction. Policy reform must introduce a statutory exception for grave human rights violations, including custodial death, torture, and sexual assault, where sanction is deemed automatic or unnecessary. This recommendation has been explicitly raised by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, citing Manorama Devi’s case as evidence that discretionary sanction enables impunity (Human Rights Watch).

INDEPENDENT SANCTIONING AUTHORITY

Current procedure centralises prosecutorial sanction within the Ministry of Home Affairs, creating a conflict of interest. A corrective policy measure would be the creation of an independent statutory authority, comprising retired judges and human rights experts, empowered to grant or deny prosecution sanction in AFSPA-related cases. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission and multiple parliamentary review submissions have noted that executive-controlled sanction undermines the rule of law (Amnesty International).

MANDATORY TRANSPARENCY IN SANCTION DECISIONS

In the Manorama Devi case, denial of prosecution sanction was never accompanied by a reasoned order, preventing judicial review. Policy reform must mandate that:

- All sanction decisions are time-bound.

- Written reasons must be published or made available to courts.

- Denial of sanction is subject to judicial scrutiny.

This procedural correction has been repeatedly recommended by the NHRC, which noted that opaque sanction decisions effectively nullify investigative findings (NHRC Annual Report 2005–06).

STRENGTHENING NHRC ENFORCEMENT POWERS

The NHRC’s role in documenting the Manorama Devi case demonstrated the limits of recommendatory authority. A policy shift is required to grant the NHRC binding powers in cases involving armed forces, including:

- Authority to direct registration of FIRs;

- Power to refer cases directly to special courts;

- Statutory protection for witnesses cooperating with NHRC inquiries.

International human rights bodies have identified this enforcement gap as a critical procedural failure in India’s accountability framework (Asian Human Rights Commission).

SPECIAL COURTS FOR AFSPA-RELATED OFFENCES

Policy reform should include the establishment of special fast-track courts for offences committed under AFSPA jurisdictions. These courts must have:

- Jurisdiction over armed forces personnel;

- Access to classified operational records under judicial supervision;

- Victim-protection and witness-anonymity mechanisms.

Such courts have been recommended in comparative international conflict-zone accountability models and cited as necessary to address systemic delays and obstruction in cases like Manorama Devi’s (Human Rights Watch).

ALIGNMENT WITH INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS

India’s obligations under the ICCPR require effective remedies for rights violations. Policy correction demands domestic incorporation of international standards, ensuring that immunity laws do not override treaty commitments. UN special rapporteur observations on extrajudicial executions have repeatedly cited AFSPA-related cases as non-compliant with international law (OHCHR).

PATHS TO JUSTICE: JUDICIAL, LEGISLATIVE, AND CIVIL SOCIETY MEASURES

JUDICIAL PATHWAYS WITHIN EXISTING CONSTRAINTS

Despite statutory immunity under AFSPA, limited judicial avenues remain available. In the Manorama Devi case, courts demonstrated that while criminal prosecution was blocked, judicial acknowledgement of wrongdoing was possible. One viable path is the use of constitutional remedies under Articles 32 and 226, allowing victims’ families to seek:

- Judicial declarations of rights violations;

- Compensation for custodial death;

- Court-monitored investigations, even if prosecution is stalled.

The Supreme Court has previously affirmed that constitutional courts can award compensation independent of criminal liability, creating a narrow but meaningful accountability mechanism (Supreme Court of India).

LEGISLATIVE INTERVENTION THROUGH PARLIAMENTARY ACTION

Legislative justice remains the most decisive route. Parliament retains the authority to:

- Amend or repeal AFSPA provisions, including Section 6;

- Introduce sunset clauses requiring periodic review of “disturbed area” status;

- Mandate annual public reporting on prosecution sanctions granted or denied.

In the aftermath of the Manorama Devi case, AFSPA reform proposals were raised in parliamentary discussions, but no binding legislative change followed, illustrating that justice through legislation requires sustained political will rather than episodic debate (PRS Legislative Research).

ROLE OF CIVIL SOCIETY AND WOMEN-LED MOVEMENTS

Civil society initiatives have proven critical in preventing the Manorama Devi case from disappearing into administrative silence. The Meira Paibi movement, women’s groups, and local human rights organisations:

- Preserved eyewitness testimonies;

- Maintained public pressure through protest and documentation;

- Facilitated engagement with national and international human rights bodies.

These efforts ensured that the case remained part of legal discourse, media reporting, and international advocacy, even when domestic prosecution was denied (Outlook India).

INTERNATIONAL ADVOCACY AS A JUSTICE MECHANISM

While international bodies cannot prosecute, they provide sustained accountability pressure. Submissions to the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions and documentation by international NGOs transformed the Manorama Devi case into a reference point for global scrutiny of AFSPA. This form of justice operates through:

Reputational accountability;

- Inclusion in UN and international human rights reports;

- Long-term influence on policy reform narratives.

Such mechanisms ensure that impunity is recorded, challenged, and internationally acknowledged, even when domestic remedies fail (OHCHR).

COMBINED PATHWAYS AND THEIR LIMITS

The Manorama Devi case demonstrates that no single path delivers complete justice. Judicial remedies provide recognition, legislative reform offers structural correction, and civil society sustains memory and pressure. Justice, in this context, emerges not as a single outcome but as an accumulation of resistance against erasure, where accountability is pursued across institutions rather than achieved through one verdict.

CONCLUSION

Thangjam Manorama Devi’s case is not merely a historical episode from Manipur; it is a living question mark hanging over the Indian justice system. It forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: when laws prioritise institutional protection over human life, justice becomes conditional, selective, and endlessly deferred. This case demonstrates that accountability cannot survive where immunity is absolute and oversight exists only in form, not in function.

The silence imposed on victims, the endurance demanded of communities, and the moral burden shifted onto ordinary citizens expose a deeper structural failure. Justice was not withheld due to lack of evidence, absence of outrage, or exhaustion of legal routes—it was obstructed because the system itself was structured to halt accountability before it could advance. Manorama’s case shows how truth can be formally acknowledged yet practically neutralised.

For us, the lesson goes beyond sympathy or anger. It is a warning. Democracies do not collapse in a single moment; they erode when exceptional laws become permanent tools, and when extraordinary powers operate without ordinary scrutiny. The future of accountability depends on whether we insist that legality must never replace morality, and that security can never justify silence.

Manorama Devi cannot be brought back. But the responsibility of what her case becomes still lies with us—whether it fades into institutional memory as another unresolved injustice, or stands as a line that we collectively refuse to let history cross again.

DISCLAIMER:

This article is based on publicly available, credible sources, including government reports, judicial records, human rights organisations, and reputable news outlets. All information is presented for educational, journalistic, and awareness purposes. The content reflects documented facts, judicial findings, and media reports about the Thangjam Manorama Devi case, the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA), and related protests. It does not include unverified allegations or speculation. The article is not intended to defame any individual or institution, and any interpretation of law or events is derived from official documents and reports. Readers are encouraged to consult original sources for verification. All embedded links provide direct access to source material, ensuring transparency and accuracy. The author and publisher disclaim any liability for interpretations, opinions, or actions taken based on the content of this article.

REFERENCES:

- https://en.wikipedia.org

- https://en.wikipedia.org

- https://www.humanrights.asia

- https://www.hrw.org

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- https://indianexpress.com

- https://nhrc.nic.in

- https://indiankanoon.org

- https://www.epw.in

- https://www.indiatodayne.in

- https://indianexpress.com

- https://www.indiatoday.in

- https://www.amnesty.org

- https://www.thehindu.com

- https://www.legalserviceindia.com