Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly, and applying the wrong remedies.-Groucho Marx

A GLIMPSE OF THE ELECTION

First Lok Saba Election - 1952

On the night of August 14–15, 1947, India officially ceased to be under colonial control. On 26 November 1949, the constitution was ratified, and it became law on 26 January 1950. India was then governed by a transitional administration. It had become essential to appoint the nation's first democratically elected administration. In January 1950, Sukumar Sen was appointed the first Chief Election Commissioner, and the Election Commission of India (ECI) was established. The Election Commission of India (ECI) realized that holding free and fair elections would not be simple in a large country like India. To hold the elections, electoral rolls needed to be created and the boundaries of the electoral constituencies defined.

An enormous amount of work went into the First Lok Sabha Election preparation. For an impoverished and illiterate nation like India, the First General Election (GE) was to be the first significant democratic test. The universal adult franchise was disproven by the Indian experiment. A significant moment in the global history of democracy was the First GE. It rebuked those who had argued that conditions like poverty and illiteracy precluded the holding of democratic elections. Mr. Sukumar Sen, who successfully oversaw the entire electoral process, was one of the first people to receive the Padma Bhushan civilian award.

The First Lok Sabha Election was held between October 25, 1951, and February 21, 1952. It was carried out in 26 states, which were divided into portions A, B, and C. There were 401 constituencies in all, with 393 seats (98%) allocated to the general category and 8 seats (2% reserved for scheduled tribes) (STs). 10.45 crores of rupees were spent on the First Lok Sabha election.

source: Wikipedia

17th Lok Saba Election - 2019

On the night of August 14–15, 1947, India officially ceased to be under colonial control. On 26 November 1949, the constitution was ratified, and it became law on 26 January 1950. India was then governed by a transitional administration. It had become essential to appoint the nation's first democratically elected administration. In January 1950, Sukumar Sen was appointed the first Chief Election Commissioner, and the Election Commission of India (ECI) was established. The Election Commission of India (ECI) realized that holding free and fair elections would not be simple in a large country like India. During the 17th Parliamentary Election, Malkajgiri (Telangana) recorded the most number of electorates (3150313) and Lakshadweep recorded the lowest number (55189 electorates).

Regarding the male and female electorates, a total of 473373748 male electorates and 438537911 female electorates were counted in this Lok Sabha Election. Maximum male electorates were recorded in Malkajgiri (Telangana), while minimum electorates were recorded in Lakshadweep.

Picture Source: Wikipedia

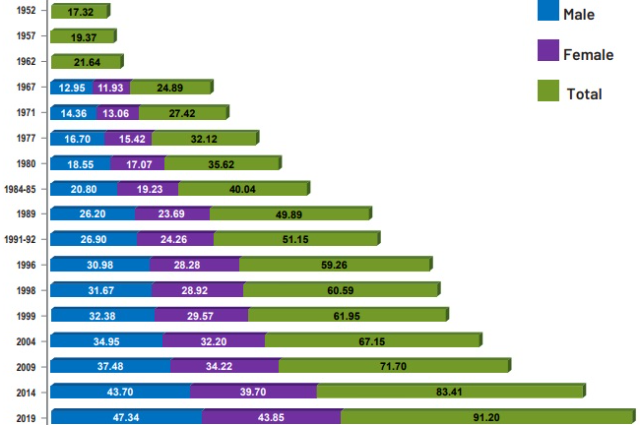

Note: Male/Female Break-up is not available for the 1952 to 1962 Parliamentary Elections

BREAKTHROUGH OF ELECTIONS

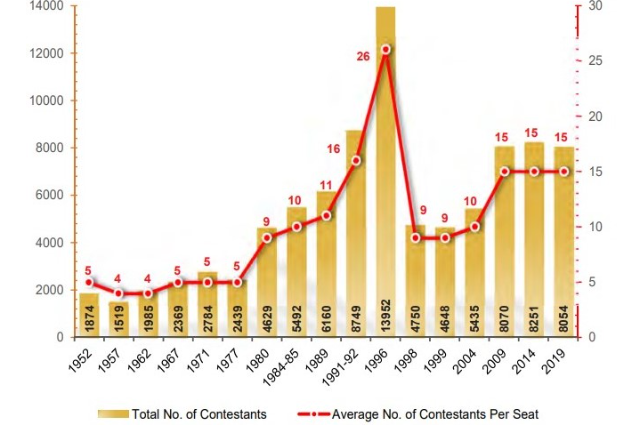

- Contesting candidates

In total, 8054 candidates filed to run in the 17th GE. This amount fell by 2.39 percent. Tura (Meghalaya) had the fewest 3 candidates running in this election, while Nizamabad (Telangana) had the most contestants running.

Picture source: election atlas

- Female Participation

The number of female candidates in the current Lok Sabha election was 726, an increase of 8.68 percent from the last election. Out of these, 226 were independents, 272 were from registered (unrecognized) parties, 171 were national party members, and 57 were state party members. Only one female candidate (each) ran in Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Dadra & Nagar Bengal, while the lowest number of elected female candidates (each) came from Assam, Chandigarh, Haryana, Kerala, Meghalaya, NCT OF Delhi, Telangana, Tripura, and Uttarakhand. Uttar Pradesh had the most female candidates running, with 106. 648 female candidates lost this election, and 575 had their deposits forfeited.

726 female candidates were competing in 2019 compared to 668 in 2014, an increase of 8.68%. With a winning percentage of 10.74 percent, 78 of these candidates were chosen for office.

From the start of the Lok Sabha Elections in 1952 until 2019, this election saw the most female candidates run, with 726.

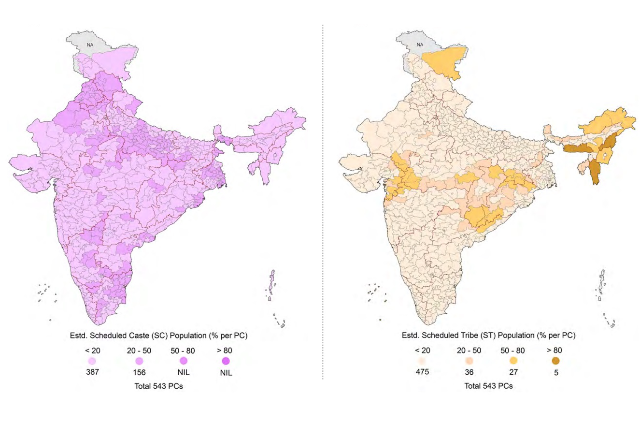

- SC/ST Candidates

From the above 2011 census, there was 20.13 crore SC people living in India, up 20.85 percent from 16.66 crores in 2001. The population of the state of South Carolina made up 16.6% of the total population in 2011, up from 16.2% in the 2001 census. The maximum SC population is 49.46 percent in Jalpaiguri (Assam). With 0.07 percent, Srinagar (Jammu and Kashmir) has the lowest rate.

Compared to the 2001 estimates of 8.43 crore, the total ST population in 2011 was 10.42 crore or 23.66 percent of the total population. The ST population increased from 8.2% in the 2001 census to 8.6% in the 2011 census. The constituency of Lakshadweep has 94.8% of the total ST population.

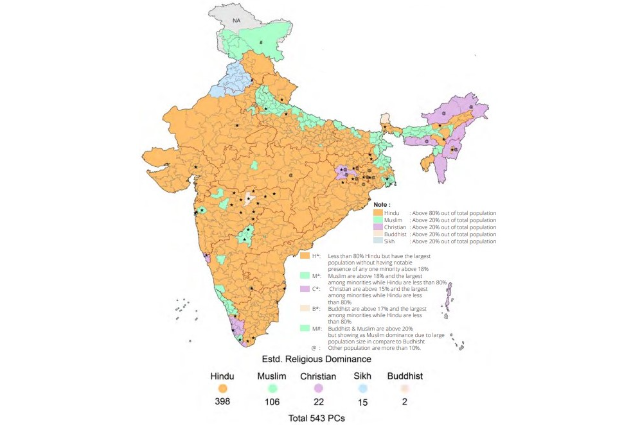

- Religious Dominance

Parliamentary districts with a majority of Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, and Buddhists are distributed as follows: 398 Hindu seats (73.30 percent), 106 Muslim seats (19.52 percent), 22 Christian seats (4.05 percent), 15 Sikh seats (2.76 percent), and 2 Buddhist seats (0.37 percent ).

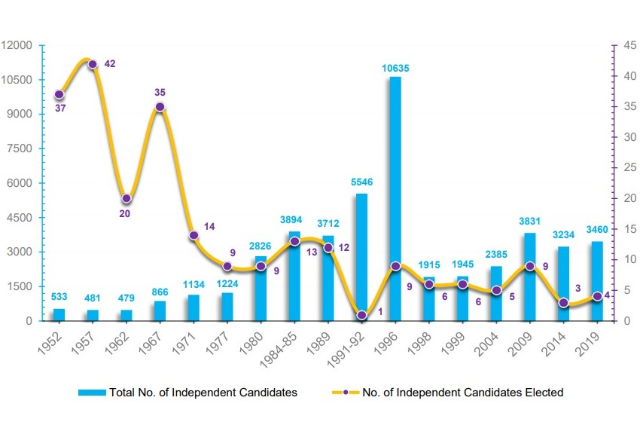

- Independent candidates

source: election atlas

POLITICS IN ELECTION

- Planning

Despite the many divisions, everyone agreed that development could not be left to the discretion of private actors and that the government must create a design or plan for it.

In truth, planning as a method of reviving the economy received a lot of support from the general public during the 1940s and 1950s all over the world. We typically think that private investors, such as industrialists and big business owners, are opposed to the concept of planning and instead want an open economy with minimal governmental regulation of the capital flow. That was not the case in this instance. Instead, a group of influential industrialists met in 1944 and prepared a joint proposal for the establishment of a planned economy in the nation. The Bombay Plan was the name of it. The Bombay Plan urged the state to make significant investments in industry and other sectors of the economy. Planning for development was therefore the most obvious option for the nation after Independence, going from left to right. The Planning Commission was established not long after India attained independence. It was presided over by the prime minister. It evolved as the most important and primary mechanism for choosing the direction and approach India will take for its growth. - Early Initiative and Five-Year Plan

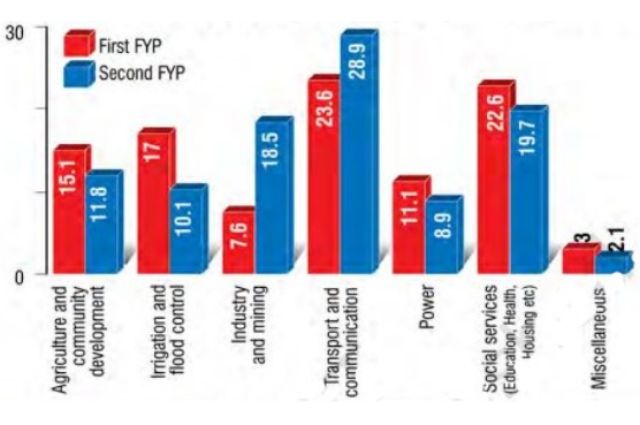

The Indian Planning Commission chose five-year plans, similar to the USSR (FYP). The concept is pretty straightforward: the Indian government creates a paper outlining a strategy for all of its incoming and outgoing funds over the next five years. As a result, the budgets of the federal government and all of the states are split into two categories: "non-plan" budgets, which are used annually for routine expenses, and "plan" budgets, which are used every five years by the priorities established by the plan. The advantage of a five-year plan is that it enables the government to concentrate on the big picture and implement the long-term economic activity.

There was a lot of excitement in the nation following the announcement of the First Five Year Plan draught and subsequently the real Plan Document in December 1951. The texts were extensively studied and disputed by people from all walks of life, including academics, journalists, personnel of the public and private sectors, industrialists, farmers, and politicians. The Second Five Year Plan was introduced in 1956, and until the Third Five Year Plan was introduced in 1961, the excitement around planning was at its zenith. In 1966, the Fourth Plan was scheduled to begin. Planning had lost much of its freshness at this point, and India was also going through a severe economic crisis. The administration decided to go on a "plan holiday." The framework for India's economic development was already in place at that point, notwithstanding the numerous critiques that were leveled at both the method and the priority of these plans. - Movements

- Chipko movement

When the forest authority denied the villagers' request to cut down ash trees to create agricultural tools, the campaign started in two or three villages in Uttarakhand. However, the forest service gave a sports manufacturer permission to utilize the same parcel of land for business purposes. The people were incensed by this and criticized the government's action.

- Party-based movement

Social and political movements are examples of popular movements, and there is frequent overlap between the two. For instance, the nationalist movement was primarily a political movement. However, we also know that discussions about social and economic issues during the colonial era sparked separate social groups like the anti-caste struggle, the Kisan sabhas, and the trade union movement in the early 20th century. Some underlying social conflicts were brought up by these movements.

- Bharatiya Kisan Union

Since the 1970s, there has been a wide variety of social unrest in Indian society. There were numerous grievances against the government and political parties, even in those areas that only partially profited from the growth process. One such instance of better-off farmers protesting against government policies was the agrarian upheavals of the 1980s.

- Fake policies

From the end of the 1960s, the narrative of development in India underwent a substantial change. Indira Gandhi became a well-liked politician. She decided to increase the state's influence over and direction of the economy. Many additional regulations on private business were introduced starting in 1967. 14 independent banks were nationalized. Numerous pro-poor programmer were announced by the government. Along with these changes, there was an ideological shift toward socialist policy. This emphasis sparked contentious discussions among political parties and academics in the nation. The support for government-led economic development did not endure indefinitely, though. Planning did go forward, but it received far less attention. The Indian economy expanded at a sluggish rate of 3 to 3.5% each year between 1950 and 1980.

Public opinion in the nation lost the trust it once had in many of these institutions as a result of the pervasive inefficiency and corruption in some public sector firms as well as the not-so-good role of the bureaucracy in economic development. As a result of the public's lack of trust, policymakers began to downplay the role of the state in India's economy starting in the 1980s.

First and second-year FYP

source: election atlas

CONCLUSION

We can better comprehend the essence of democratic politics by studying the history of these popular movements. As we have shown, these non-party moves are neither irregular nor problematic. These movements, which were created to address some issues with how party politics operate, should be viewed as an essential component of our democratic politics. They stood for newly formed social groups whose social and economic problems were not addressed by electoral politics. Popular movements made sure that various groups and their concerns were well represented. This lessened the likelihood that these groups would turn against democracy and engage in protracted social war. Popular movements offered fresh suggestions for engaging in active participation, expanding the definition of participation in Indian democracy.

Many times, opponents of these movements claim that collective actions like strikes, sit-ins, and rallies interfere with governmental operations, slow down decision-making, and undermine democratic norms. Such a claim raises a more fundamental query: why do these movements use such assertive modes of action? This chapter has demonstrated how popular movements have sparked justifiable public demands and drawn substantial public support. It should be underlined that the groups sparked by these movements are poor, economically, socially, and politically marginalized members of society. The movements' frequency and tactics indicate that these socioeconomic groups' voices were not given enough room in democracy's everyday operations. This is possibly the reason these groups started organizing large-scale protests and mobilizations outside of the voting booth.

References

- https://m.jagranjosh.com

- https://www.epw.in

- https://www.brookings.edu

- https://www.nytimes.com

- https://www.nytimes.com

- https://thenevadaindependent.com

- https://www.cbc.ca

- https://time.com/

- https://www.history.com

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca

- https://www.washingtonpost.com